https://www.austinchronicle.com/screens/1999-03-12/521557/

The Man Who Wasn't There

By Anne S. Lewis, March 12, 1999, Screens

|

|

With practically no time to prepare, I ran out and rented Kurt and Courtney (1997), shoved it into the VCR, and started frantically dialing a coterie of UT documentary makers in search of fodder for the next day's interview. As I left messages on answering machines of these filmmakers (some of whom I knew were out of town, and others of whose phone numbers I was uncertain), I kept redirecting my attention to the video, seeking clues as to who Broomfield was from his flat, unemotive, Brit-accented narration of his no-holds-barred investigation of the facts behind Nirvana rocker Kurt Cobain's death.

A short while into the film, my task became a lot easier -- there was Broomfield, no longer the disembodied interrogator, but now fully visible on the screen, formidably wired from the waist up with sound equipment, boom mike, and earphones, doing a sort of Mike Wallace/Ross McElwee/Jerry Springer number on anyone from Seattle to Los Angeles who might know something or have an opinion as to whether Kurt really killed himself -- as officially pronounced -- or was offed at the behest of his wife, Courtney Love, the theory propounded by her tough-loving dad. Broomfield wielded his mike and cameraman like a foil, barging in on the unsuspecting and drug-addled, en-guarding them with his boom mike and blunt questions (and disbelieving "Really!"s), looking for some socko way to put it to Courtney, who during production had gotten wind of the film and done everything she could to roll boulders into its path. (She would later succeed in having the finished film yanked from Sundance in 1998, and, with all the publicity that generated, guarantee its successful distribution.)

The phone rings and we watch Broomfield pick up the phone and overhear his Showtime sponsor announcing that they're yielding to pressure to yank his funding. My phone rings and it's doc maker Paul Stekler returning my call from a pay phone at the Newark airport. He suggests I call his colleague, Richard Lewis, who worked with Broomfield on Aileen Wuornos: The Selling of a Serial Killer, and gives me Lewis' home phone number, a number different from the one I'd left a message on earlier. "Here's what I'd like to know," Stek said, before dashing for his plane. "Why don't you ask him how his filmmaking evolved from his early cinema vérité style -- where he's totally in the background -- to where he's now actually in the film? Oh, and maybe ask him if he's ever thought about making a film about some, uh ... "sweet" topic -- maybe something having to do with, say, public affairs?" Perhaps a bit of projection on Stek-the-consummate-political doc maker's part, I chuckle to myself, before the line is clipped by my call-waiting signal -- the wrong Richard Lewis returning my call.

The "right" Richard Lewis and I play phone tag right up until Sunday midmorning, my planned early afternoon phone call looming. "Now, you wouldn't write anything that makes Nick mad at me would you?" Lewis demands right off the bat. "Oh, no," I reassure him with my fingers crossed. "Broomfield thrives on controversy, you know," Lewis explained, "his style is very combative, in-your-face. He thrusts himself into other people's lives and then becomes a player himself. It becomes 'his' journey. Remember Michael Moore's Roger & Me? Broomfield's films tend to be structured like that, where the person the film's really about -- Aileen Wuornos, Maggie Thatcher, Courtney Love -- is not present."

Did you learn anything from working with him for a year? "I was right out of graduate school then and I thought documentaries were 60 Minutes -- you know, intercut talking heads. I started cutting Aileen Wuornos like that and Nick starts screaming, 'What are you doing?' He doesn't do talking heads answering each other; it's a linear progression through the story. Broomfield's definitely had a positive influence on my filmmaking, as far as the storytelling aspect goes. He's a real perfectionist; he knows the story he wants and keeps working at it until he gets it right. Good isn't good enough -- it has to be great. As far as the mise-en-scène aspect of a film, Nick doesn't care much about lighting or production values."

Before he signs off he gives me the number of a cameraman in town who'd worked with Broomfield and who he thinks would have a lot to say. I call and leave a message.

While I wait, I decide to see if I can find anything useful about Broomfield on the Web and come across an interview in which he answers the very question Stek wanted me to ask: how he moved from the silent, unacknowledged observer to an actual character in his own films. Broomfield explained there that he'd come to realize that his observational films left out what, in hindsight, he believed to be the most revealing scenes, namely, those that showed the process of making the film. By putting himself into his films, he discovered that he was able to get closer to what was really going on and what his subjects were really like. Hence the switch to the diary form.

|

|

When asked whether having him as our guide leaves us with enough wiggle room to disagree with his interpretations, the filmmaker said he believed that, unlike the authoritarian narrators of traditional documentaries, his hit-or-miss, shoot-from-the-hip style gives the audience enough subjective information about him to be able to question his objectivity.

My Caller ID flashes a wireless call and I pick up; it's Austin cameraman Paul Kloss returning my call. Kloss shot Broomfield's 1994 Heidi Fleiss: Hollywood Madam. Broomfield's brochure describes the film as a "lively, bawdy fascinating first-person chronicle of Mr. Broomfield's efforts to track [Fleiss] down." A blurb, from Newsweek, below, says that watching the "fascinating" film "with its parade of pimps, madams, hustlers, call girls, informers and cops, you quickly catch on that nothing (sic) can be trusted. Everyone lies. Its (sic) Rashomon deep fried in sleaze."

Me: So, Paul, what surprised you the most about working with Broomfield?

Paul Kloss: I always thought you got the most out of an interview by making your subject feel as comfortable as possible, so it struck me as very odd -- at least at first -- to discover that Nick liked to put his subjects into a state of uneasiness. Think, for example, about the way you shoot a typical TV news interview: You'd arrive carrying your sound and lighting equipment at your side, you'd wait to get invited in, you'd walk around the place, pick a nice spot, light it, and then sit down to shoot the interview. With Nick, you're driving down the street, shooting him driving down the street; you shoot him getting out of the car and knocking at the door and when the subject opens the door, you're shooting them. Now, these people know that he's coming to interview them, but they're usually not prepared to open the door to a running camera -- when they see that -- Nick with his sound equipment, me, with the camera on, and an assistant -- all they want to do is get away from us. Sometimes that works really well; after a while I started to see the beauty in it. In a way you get an almost more candid reaction from them, they don't have time to get into character or come up with a defense or anything, no time to prepare -- even though, yes, they were expecting him.

Me: I bet people are disarmed by his British accent.

PK: Yes. But he's certainly not afraid to ask some direct, confrontational questions. And when people react negatively, he just responds right back. One time we were filming Peter Sellers' daughter, Victoria Sellers, who was a good friend of Heidi. We'd been trying to track her down for a long time and finally arranged an interview. She's this scatterbrained type and the interview was not going well. Nick stopped the camera and said as much, in essence demanding that she be a better interviewee. She denied it at first: "What? What? I'm answering you right!" He told her he knew there was more to the story than she was telling him and if she didn't come out with it, they'd best just forget it. She did much better.

Me: She obviously wanted to be in the film. Do people usually want to be in his films, is that why they agree to talk to him?

PK: Well, uh, usually they were being paid. In L.A., especially for that film, no one's going to talk to you unless you pay them. Some of the characters we were dealing with were pretty shady.

Me: How does being paid affect their credibility?

PK: Usually they appear more than once in the film so the viewer gets to know them as characters and is then able to judge their credibility.

I anxiously glance at the clock -- ever cognizant that it's six hours later in London -- and decide that no matter how late, I simply must watch the rest of Kurt and Courtney before I talk to Broomfield. I slide the cassette back into the machine for the last 20 minutes. Darn if that's not Broomfield leaping onto the stage at an ACLU banquet where Love, the guest speaker, whom we've just seen in graphic footage to be no booster of the fourth estate, has just finished extolling the beauty of the First Amendment. Broomfield, filming from the audience, can restrain himself no longer. He impulsively hands the running camera to his companion with orders to keep it aimed at the stage and, hijacking a podium, launches into a statement condemning the ACLU's hypocrisy in honoring the famously media-threatening Love. Then he's strong-armed off the stage.

|

|

Kurt and Courtney will be presented as part of the Texas Documentary Tour on Wednesday, March 17 at the Alamo Drafthouse, at 10pm. Admission is free to Texas Documentary Tour pass-holders and SXSW pass- and badge-holders; single admission is $6. Nick Broomfield will introduce the film and conduct a Q&A session after the screening. The Texas Documentary Tour is a co-presentation of the Austin Film Society, the University of Texas RTF Dept., The Austin Chronicle, and SXSW Film.

The Austin Film Society and SXSW Film are presenting three other films by Nick Broomfield during the SXSW Film Festival:

Driving Me Crazy (1988). Originally conceived as a film about an Andrew Heller production of the musical Body and Soul, Broomfield's documentary ultimately becomes an exposé of show business. (Tuesday, March 16, 8pm, Dobie).

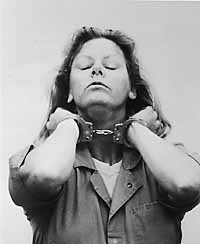

Aileen Wuornos: The Selling of a Serial Killer (1993). Broomfield delves into the commercialization of Aileen Wuornos, who is cited as the world's first female serial killer. (Tuesday, March 16, 10pm, Dobie).

Soldier Girls (1983). The film documents a platoon of women undergoing basic training at Fort Gordon, Georgia. (Wednesday, March 17, 8pm, Alamo Drafthouse).

Copyright © 2024 Austin Chronicle Corporation. All rights reserved.