Counting the Dead

Nevada journalist tries to do what the government won't

By Amy Kamp, Fri., Feb. 27, 2015

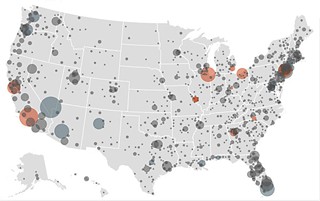

Reno News & Review Editor D. Brian Burghart first became interested in the number of law enforcement-involved deaths in 2012. While reading reports about the police shooting of a driver of a stolen car, he noticed "a gaping hole ... in every single news story I read about the incident," he wrote on his website, Fatal Encounters (www.fatalencounters.org). "There was no context. I kept looking for a sentence that said something like 'This was X person killed by police in Washoe County this year.'" When he learned no record of "how many people died during interactions with police in the United States" had been compiled, not even by the Department of Justice, "the entity logical to assemble it," he decided to make his own "comprehensive, searchable database of people who die for any reason through fatal police encounters."

Burghart says his website, which includes vetted submissions from the public as well as data from open records requests, is "more comprehensive" than other lists of law enforcement-involved fatalities, but remains far from comprehensive. He believes he's currently compiled about 30% – a number he says he arrived at with the help of expert statisticians – of all such deaths in America since 2000. Burghart draws the line at the turn of the century, and also at the point when a person is booked into a jail or other correctional facility – a count of the use-of-force deaths that occur within jails and prisons isn't within his current project's remit.

Perhaps the most ambitious part of the project is his plan to make "public records requests of every state and law enforcement agency" in the country. Burghart currently has 10 states he considers "complete," although he admits that there's "no way to verify completion," and that "every time we say it's complete, we find one we missed." Houston attorney Scott Hooper is in charge of making the requests here in Texas. Hooper says that when he first volunteered for the project, he had no idea what he was in for – there are nearly 2,000 separate law enforcement agencies in Texas. Hooper sends out a letter to each agency asking for records of "all incidents in which a law enforcement officer employed by [the] agency discharged a firearm resulting in injury or death of a human being from January 1, 2004 to present."

Burghart points out that, when it comes to "official numbers," even the FBI's Uniform Crime Reporting Program only collects the data that states volunteer, which can lead to a skewed perspective. For instance, Florida doesn't report its numbers to the FBI. Fatal Encounters is "near complete on Florida and [the rate of deaths in custody] is double what it is in New York state," says Burghart. Americans hear more about police-related fatalities in New York than in Florida or the West, but New York is "not the worst place."

As for insights that can be gleaned from the data, Fatal Encounters collects the street address for each death, because the "next iteration is to compare zip codes to the census" to get an idea of the socioeconomic status of the communities where fatalities take place. From what he has compiled so far, Burghart says, that although "minorities are represented at higher levels," the phenomenon isn't so much "a war on black people" as "it's a war on poor people": The biggest factor in the likelihood of use-of-force death is economic status.

Ultimately, the goal is that people can "look at their own areas, determine policy changes in their states and jurisdictions," depending on the types of deaths that are occurring. For instance, they could examine the correlation between their local law enforcement agencies' high-speed chase policies and people killed by cars or other vehicles. Another "big untold story," according to Burghart," is the police's relationship with the mentally ill. While they probably account for about a third of deaths, in areas where cops have proper training in how to deal with mentally ill people, those numbers go down. The correlation, he says, is as "plain as the nose on your face."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.