Arms on Brazos

As it nears completion of an extended 'Great Streets' rehab project, has Austin learned any lessons?

By Richard Whittaker, Fri., Aug. 5, 2011

There's good news for Downtown residents and regulars. After more than two years of ongoing construction, Brazos Street is scheduled to reopen in September. With that long-delayed conclusion, Brazos becomes the latest beneficiary of the city's Great Streets Program, designed to make the urban core more livable, walkable, and commercially viable. The big difference between this and other Great Streets projects is that this is the first time the city ran the project completely by itself – rehabbing an existing street, rather than cajoling or incentivizing developers to do the job for them.

So how did the city do?

Public Works supervising engineer Kevin Sweat's concern about the public response is apparent: He's concerned that the project's length will have overshadowed its achievements. Three years ago, Brazos was a mess. Narrow sidewalks at Sixth Street meant overcrowded bus stops, and there was no street-level sidewalk at the Eighth Street intersection. Some blocks sloped awkwardly into the roadway, others had steps at either end, and there was no cover from the sun. Considering this is all within a block of major state and federal offices, on a street that crosses Austin's central entertainment district, and with two major hotels and a cathedral on its length – well, that's embarrassing. Call that state of affairs Point A. The finished project – Point B – is now in sight. Sweat's best estimates have the final work crews finishing in August, September at the latest.

The Brazos Streetscape Improvement & Reconstruction Project is about more than prettying it up by adding a few benches and trees. It has meant a wholesale rebuilding of all 10 blocks from Cesar Chavez to the Capitol, with new gas mains, new water pipes, a redesigned roadway with new traffic patterns, a broadened sidewalk, and yes, benches and trees. There will even be an interactive art installation by the Sodalitas Art Group: ambient street noise will be collected with microphones, then remixed with notes triggered by infrared "keys" before being replayed in a listening area by the Whitley Building at Third Street.

The result will be a complete transformation from the old, crumbling Brazos – but we're not there yet. When the city first green-lit the reconstruction, it scheduled 420 calendar days, starting in October 2009. That came after a round of prep work by private utilities, so, Sweat said, "The public has seen construction going on longer." However, that 420-day target passed more than six months ago, and the current estimate is for 680 days, leaving Brazos in construction limbo for almost two years. However, the project is still under budget. The design was originally budgeted at $17 million, but a cost-conscious city capped the contract at $12 million. Then the global economy collapsed, construction costs plummeted, and rather than cut the design, the city was able to rebid the contract for a bargain-basement $10.5 million. Even with the delays, Sweat said, the final price tag should still only be around $11.5 million.

Insert Plan A Into Urban Slot B

As anyone who has put do-it-yourself furniture together in the wrong order knows, the key to any engineering project is the sequencing. Get it right, and you have a chance of hitting the deadlines; get it wrong, and say goodbye to your weekend. Shutting the entire street for more than a year was a nonstarter, so the city and prime contractor Cash Construction had to find other ways to break the job down. The initial challenge, Sweat said, was "making sure that there was always enough work to keep all the subcontractors on-site and busy as opposed to having to remobilize." The city originally just wanted to work on one half of one block at a time, while Cash Construction proposed splitting the job east-west, shutting the entire 11-block stretch down one side, then the other. The city's plan meant risking the loss of subcontractors between stages; Cash Construction's plan would have been massively disruptive to tenants, pedestrians, drivers, and businesses. So they compromised on four blocks at a time. That way, Sweat said, "If something went horribly wrong, at least we would have both sides of the street completed up to Sixth Street."

So why the delay? There was no singular disaster, and in fact the final streetscape is pretty close to the 2009 designs. A few benches changed in orientation, some bike racks shifted, and cut-in parking bays were sacrificed so the project could move cover-creating trees from the shady west of the street to the more exposed east. However, the project became a lesson in time-consuming compromise, driven by unexpected surprises. Think of it like Schrödinger's Cat, the legendary scientific paradox: Until you open the cat's box, you don't know if it's alive or dead.

In this case, the engineers did not really know what they were facing until they opened the road surface. The first metaphorical cat surprise was a pedestrian tunnel between One Congress Plaza (just north of Cesar Chavez) and the parking garage on the other side of Brazos. That added 60 days to the contract as engineers hand-tunneled a storm drain underneath it. Add on 50 days for extra street furniture, 40 days for the new limestone retaining wall and sidewalk next to Central Presbyterian Church, 70 days for extra utility work, 10 days suspended around special events like the Pecan Street Festival, and 10 bad weather days for rain. Every single extension had to be requested by the contractor as a contract change order, recommended by the relevant board or commission, then approved by council. However, add it all together, and those sporadic extensions added up to grand total of 260 extra days – an almost two-thirds overrun.

The Art of the Possible

That is the kind of overrun that can be tough to explain to residents. Sweat praised the Downtown Austin Alliance for helping with the project, but in a way it was really the DAA's idea. The alliance's Streetscapes & Mobility Committee staff liaison Thomas Butler said, "We knew, maybe before the city did, that it was going to be done." The sidewalk was last upgraded in 1999 as part of a limited project around Sixth Street to meet Americans With Disabilities Act standards. When the city proposed similar upgrades for all of Brazos in 2003, he said: "There was no Great Streets sidewalk included. The Alliance convinced the city to add those improvements into the 2008 bond package, because we knew that if they reconstructed that street without doing the sidewalks, it would be a long time before they would go in and tear it back up." In turn, the DAA served as an intermediary, keeping the locals informed and bringing concerns to the project team.

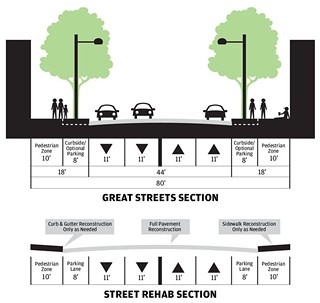

In the case of Brazos, project managers had to modify the standard Great Streets design, getting rid of some features like cut-in parking bays and using on-street parking instead. Brazos will remain one-way for the foreseeable future, but the roadway was designed so it can be converted to a two-way street if the city changes its traffic management plans.

Previous Great Streets projects, like Second Street, were tied to major condo and office developments already rearranging utilities – Brazos was about rehabbing an existing street. That meant working around a lot of existing utilities, like maintenance covers and electrical access panels, and that also meant compromising on street layout and furniture. Such things may not sound like a big deal, but a trash can or streetlight two feet from its ideal position can make a big difference on appearance and usability. Take the southeast corner at Brazos and 10th streets: At its narrowest, its walkable sidewalk is only about 40 inches – tough going for a pedestrian, near impossible for someone in a wheelchair.

Other compromises were about timing. Some were spur of the moment; for example, during South by Southwest 2010, digging behind the Paramount Theatre was quickly suspended when city staff realized that heavy equipment was shifting dirt within feet of long audience lines. Other compromises took some serious planning; rather than risk closing any of the structured parking garages midweek, contractors had to hustle through the weekend, picking materials that would be car-ready by Monday morning. That may have been an inconvenience for the garage owners, but it was the smaller businesses that suffered most. Sweat said: "I kept hearing people say, over and over, 'Even in a good year, we're month-to-month financially.' Then when our construction came in, typically there was at least a two-month period when they were directly affected." Financially, there was little Sweat could do since the city has no mechanism to reimburse businesses for lost revenue. But, he said, "Most of them seemed to endure it, and now that it's finished, they do seem to be reaping the benefits of a more pedestrian-friendly environment."

So does Downtown Austin Neighborhood Association President Michael McGill think the new Brazos is more pedestrian friendly? "I think so," he said. McGill lives at the Railyard Condominiums at Fourth and Brazos and has been on both sides of those construction compromises. For example, the city redesigned the corner near the condo's main entrance to get rid of an awkward step. Similarly, the Street Orchestra art installation was originally to be sited under the Railyard windows, but residents convinced the project managers to move it a block south, next to commercial properties. Yet they still had to contend with time-sensitive, late-night, and rescheduled weekend work. "That's something that doesn't get ruled into noise ordinance issues," he said. As a Downtown resident, he is used to noise: "Friday, Saturday night, I'll sleep with my windows open. I don't really care. But construction noise is a totally different matter – having a jackhammer at 5, 6 in the morning." While he understood that concrete pouring had to be done at night, "there was a lot of other stuff that doesn't have to happen at night or in the early morning hours that was certainly impacting people."

The lane closures meant drivers had to take their share of the inconvenience, too. For Capital Metro, which runs 12 routes along Brazos, a road reconstruction is a mix of pain and opportunity. The pain comes from rerouting, and over the last two years, staff could do little but shift buses to Congress and clock-watch. Cap Metro Principal Planner Roberto Gonzalez said, "We were told they'd be ready by the fall of 2010, and now we're slowly approaching the fall of 2011." However, Cap Metro played its own role in the construction. Gonzalez explained that a street redesign gives Cap Metro an opportunity to take "a second look at our bus stops and say, 'Are they all in the right places?'" Brazos was a particular headache: Some stops were right next to parking spots, meaning buses had to pick up passengers in the middle of the road. Between the agency's quarter-cent funding of the city's street reconstruction budget and its own contributions toward street furniture, Cap Metro was able to change the plan to fit its needs and add its own components. When talks with the city began, Gonzalez said Cap Metro only wanted stops at "a few key blocks." Those stops may be more user-friendly, but there will be fewer – dropping from six down to three.

And how well did Cap Metro handle the diversions? There are no signs on Brazos telling passengers where to go, and none on Congress saying which buses were diverted to which stops. Even the online trip planner still sends passengers to Brazos, with the uninformative coda of a blinking exclamation mark indicating "Route may be affected by detours." After two years, the obvious question becomes: How hard is it to print some new timetables? Gonzalez explained that even though routes are redrawn every six months, the "Brazos project hit us in the middle of the cycle. ... The way some of our systems handle times and time points and schedules, there were a handful that we could not change suitably."

Once the project wraps, it is the permanent compromises that everybody will have to live with. Consider the trees, an essential part of the Great Streets design. On this project, they ran afoul of a different kind of trunk. Brazos is a main route for much of the Downtown telephone and data system, and the cables were replaced only two decades ago. But when city contractors opened up the road to expand the sidewalk, they found the telephone engineers had left the cables closer to the surface than anyone expected. Sweat said, "Because this wasn't a street-widening or transportation improvement project, we really didn't have the legal authority to get them to move." That meant the city could not simply plant every tree straight into the sidewalk, and instead had to design above-ground planters with enough drainage and irrigation to make sure they could survive Austin's erratic and punishing weather. The city could not even get enough of the trees it wanted; a national shortage of Bigtooth maple means most planters contain Texas Ash.

A History Lesson

Ironically, once this project is complete, Brazos will look like it did 50 years ago. There is a certain myth about Downtown Austin pre-Great Streets: dead in the daytime, deader at night. If you ever feel like busting that myth, just visit the Texas Film Commission's Texas Archive of the Moving Image website and type in "Congress Avenue." In the 1940s, Austin's main street looked like New York's 42nd Street on a busy Saturday. It was a dense throng of stores, each garlanded with advertising signs, many with awnings to keep the sun off the crowds. In fact, it kind of looked like what is being built now.

So what went wrong?

City Downtown Officer Mike Knox blames the rise of the suburbs. He said: "Everybody moved out. All that was really left in Downtown was offices, and back in the Eighties, even that was in bad shape." The exodus was reflected in the collapse of retail. At its height, there were 120 shops on Congress, including half a dozen major department stores. By the early Nineties, that had shrunk to 12 retailers, and "three of them were T-shirt shops and museum stores." In recent years, that number has trebled; the reversal began 14 years ago, when Kirk Watson became mayor and set the pieces in place to revive the area. Knox said, "We tend to like to say that we have this vision of Downtown and we've been building toward it, but the reality is that it's been a whole series of opportunities and ideas." The first big stage was easy: Over the prior three decades, the city had acquired several blocks to build a municipal government center around Second Street, "but that didn't pan out, so we had all this land." Add on some easily demolished, crumbling warehouses and underused parking lots, and the potential for development was obvious. Even Knox is amazed how fast the city has evolved: "We went from three- and four-story buildings to a 56-story building in 10 years."

However, unlike Second Street, Brazos was not a clean slate, and so the project had to work around those three- and four-story buildings. Many have tenants, and some have cellars extending under the sidewalk. Sweat's big fear was that they would be damaged by his construction teams, so he had vibration meters installed, and, he said, "That sometimes meant the contractor had to use smaller tools that take longer to do the job." Then there were the water lines; an expanding Downtown population means more water in and more waste out. So Austin Water took advantage of the open road to replace the mixture of 6-, 8-, and 12-inch cast-iron pipes with new 12-inch ductile iron pipes. Again, Schrödinger's Cat took a swat at the timetable: Only after the road was opened did Austin Water realize that several water meter vaults were in disrepair and needed replacing. While this was happening, Sweat said, "almost on a weekly basis, the old line was rupturing."

Increasingly, the new, dense Downtown Austin is running up against the old, dense Downtown. In Knox's City Hall office, there is a stack of color-coded maps that break down each Downtown lot. Red means no potential for redevelopment; green indicates short-term redevelopment. What may be surprising is how few blocks are one single hue; they are instead a mix of greens and reds, as well as orange for historic structure, blue for government buildings, and the more speculative yellow for long-term development opportunities. What that means, in simple terms, is that the city is running out of big, easy targets of opportunity for the Great Streets Program. Instead, future projects will look more and more like the Brazos experience, contending each time with the old infrastructure.

What Would Van Halen Do?

The new Brazos is getting close to its debut. The last major stretch of work – the west side of the street between Ninth and 11th – is nearly completed. There is also the smell of fresh tarmac at the northeast corner with Sixth (another concession: The project management team agreed to work around the Driskill Hotel's busiest times, coming back to finish this stretch out of season). The day the contractors seal the surface, Schrödinger's Cat is back in the box. The real test will only take place when all the barriers come down and Austinites can freely drive and walk up the street.

Ever hear the story about Van Halen and the brown M&Ms? The legend is that, out of rock star hubris, the band's contract rider requirements included a bowl of M&Ms with all the brown ones removed. That clause was real, but it was said to really be a test determining whether the venue's management was paying attention. In his autobiography, vocalist David Lee Roth wrote that the first time they went to a venue and found brown M&Ms in the bowl, it turned out as well that the stage was not weight-rated for the band's equipment. End result? The stage set sank through the floor, causing $80,000 in damage.

In that vein, contractors and developers wonder whether this city-run Great Streets retrofit has been held to the same standards as their public/private versions. Meanwhile, the city and residents are watching to see if the design compromises really worked. Take, for example, the raised tree planters. During construction, McGill said, "these were empty pits, and they were just trash collectors. It was unpleasant, and they didn't really clear them out that much." However, he applauded their irrigation systems. "There's a lot of trees that are dying Downtown," he said. Sweat himself was unhappy that the compromise design – raised planters – reduces usable sidewalk space, making it difficult to open car doors or unload Cap Metro passengers. The planters' limestone is softer than Austin's trademark tough granite, and some are already chipped from everyday use. During June's heavy rain, many drained poorly, leaving roots waterlogged while overflowing water poured over the embedded light fittings. Several saplings have died already (although in this scorching summer, many trees planted directly into the ground are not faring much better). Three mature trees on the 400 block are already growing into the protective metal grills that surround their bases. These circular grills are designed to be cut back as the sapling matures, meaning the roots stay covered while the trunk gets thicker. That cutback has not happened, and now the metal is cutting into the trees' trunks. That's the sort of oversight that gets noticed by pedestrians and shopkeepers and could undermine the public image of the entire project.

With the last few items left to be finished before the city signs off, the Brazos project is now less about the engineering problems and more about learning opportunities. Even if every engineering glitch were unavoidable, a 62% schedule overrun could cast a long shadow over future projects. The next funded Great Streets targets – like Second Street running to the Austin Convention Center, and the upgrading of Colorado – could make Brazos look like a dig in a kid's sandbox and would be nothing compared to the recently proposed upgrades to Sixth Street. Even mentioning making Austin's busiest entertainment district temporarily less walkable makes every stakeholder blanch, and not just for the business losses: Drunken people and big holes in the ground are a bad combination. Still, those streets do need rehabbing. "All of that work is both important and disruptive, so there's a lot of balancing to do," Council Member Chris Riley said. "Before we dive into other Great Streets projects, we need to look at what has happened on Brazos and see if there are any lessons to be learned."

Sweat and Riley agree that Brazos shows the city may have been right in its originally proposed scheduling: smaller pieces, going block by block if necessary. Add that to the lessons learned from earlier projects. Take Congress Avenue, which, although not technically part of the Great Streets Program, was the city's first big Downtown rehab project. Riley said, "Today, when you walk down Congress, you see what we did, and it looks very different to what we would do today." No diagonal cut-in parking, for a start. As more restaurants and cafes start serving on the sidewalks, that lost pavement creates choke points for pedestrians. Yet simply removing those parking slots also means fewer places to park, and, as the resurgent controversy about meter hours proves, the city, developers, and Downtown businesses have a long way to go on a coherent parking policy. Great Streets, Riley pointed out, are never supposed to be anti-car, and he is frustrated that so much of Downtown remains one-way, blocked off, or just plain baffling to drivers. By the same measure, he was greatly disappointed that Cap Metro (on whose board he serves) seemed so ill-prepared to deal with long-term diversions.

As the Great Streets Program moves deeper into thriving areas, the city will find more challenges in hitting the balance between the long-term gains and short-term disruption. The Downtown Austin Alliance's Thomas Butler argues that the lessons from projects like Brazos are being learned by "both the executive-level staff and those down in the trenches." Sweat argues that should mean "having the hard conversations with the businesses about severely limiting their accessibility for shorter periods of time to get it done quickly, or [instead] trying to maintain their access, knowing that's going to affect the duration of the contract." If the Brazos experience is any guide, it's a balance that requires both long-term vision and short-term attention to detail.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.