Are Fire Marshals Shirking Their Duty?

Fire experts testify in Willingham wrongful conviction case

By Jordan Smith, Fri., Oct. 22, 2010

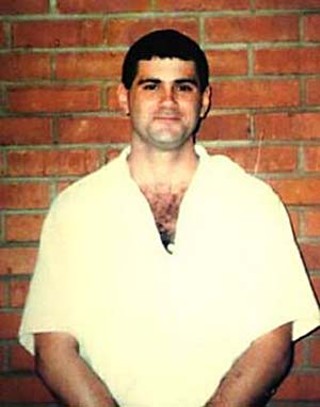

In court testimony last week, two nationally recognized fire-science experts roundly discredited evidence that sent Cameron Todd Willingham to the death chamber for the 1991 arson-murder of his three children in his Corsicana home. Florida-based expert John Lentini and Austin-based Gerald Hurst testified during a hearing before District Judge Charlie Baird that there's no proof the fire that killed the children was intentionally set. Further, both experts questioned why anyone would continue to defend the science that the state used to convict Willingham – unless, of course, they are intent on ignoring the so-called "duty to correct," which compels scientists to admit when they've provided incorrect evidence or testimony in a criminal case. That's exactly what it appears state Fire Marshal Paul Maldonado has done, testified Lentini, by penning an Aug. 20 letter to the Forensic Science Commission that his office stands by "the original investigator's report and conclusions." Barry Scheck, co-director of the Innocence Project and one of the team of lawyers representing Willingham's surviving relatives, asked Lentini if there was any way to explain Maldonado's steadfastness. Lentini replied, "Only if someone is holding a gun to his head or is trying to avoid the duty to correct."

The testimony was part of a roughly three-hour hearing Oct. 14 in Baird's court. Willingham's relatives are asking Baird to find that Willingham was wrongfully convicted and that there's enough evidence to warrant opening a formal court of inquiry to determine if any state officials (i.e., the Fire Marshal's Office and/or Gov. Rick Perry) committed official oppression by allowing Willingham to be executed despite having been provided compelling scientific evidence challenging the propriety of his conviction.

The lawyers closed the case, and Baird took the evidence into consideration, just minutes before the 3rd Court of Criminal Appeals issued a stay in the case, ordering Baird to stop until an argument made by Navarro District Attorney R. Lowell Thompson can be sorted out and whether Baird should be hearing the case at all. The hearing was initially scheduled to take place Oct. 6, but Baird stayed the proceedings to consider Thompson's motion asking Baird to recuse himself from the case due to evidence (albeit contradictory) suggesting Baird could not be impartial: As a judge on the Court of Criminal Appeals, Baird had once ruled on Willingham's case, in favor of upholding his conviction; more recently, he was given the Courage Award by the Texas Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty.

At the start of court last Thursday, Baird said he'd considered the motion and was persuaded by the arguments of the attorneys for Willingham's family – including Scheck, former Gov. Mark White, and San Antonio attorney Gerald Goldstein – that Thompson was not actually a party to the proceeding, and thus had no standing to ask for Baird's recusal. Thompson seemed flustered by that decision, and, as it turns out, he left Baird's courtroom and went several blocks east to the 3rd Court's offices to file for a stay, which Chief Justice Woodie Jones granted. The order gives Scheck, White, and Goldstein until Oct. 22 at 5pm to respond. (Baird will be allowed to issue his findings if and when the court tells him he may do so.)

Lawyers for Willingham's family questioned Lentini and Hurst about problems with the evidence former fire marshal's investigator Manuel Vasquez (now deceased) testified to during Willingham's 1992 trial. At issue is the fact that some of Vasquez's conclusions were not even then supported by the standard of care for fire investigation, said Lentini. Some of his incorrect assessments were widely believed at the time, including the notion that rapid heating creates spiderwebbing in glass, a myth that Lentini ultimately debunked in 1992 (known as "crazed glass," it is in fact created only by rapid cooling, such as when water hits hot glass). But most of the assertions in Vasquez's initial report, and later in testimony at Willingham's murder trial, were not consistent with the established and accepted science. Lentini should know: He was among the experts who wrote the National Fire Protection Association's manual on fire investigation.

Among the things Vasquez got wrong was the idea that burn patterns on a floor prove that an accelerant has been used to set the blaze. Those patterns, Lentini said, are actually created because items on the floor protect it from burning to the same degree as exposed flooring. Moreover, he testified that at the time of the Willingham fire, scientists had already shown that inside a room, fire will consume everything in its wake – burning underneath beds and tables, for example – as a result of a phenomenon called "flashover," in which fire rises to the ceiling and then consumes the room from the top down, eating fuel created by combustible materials, including furniture.

Hurst was the first to challenge the conclusion that the Willingham fire was arson. Back in 2004, just weeks before Willingham's execution, Willingham's cousin Pat asked him to review the evidence; he did, and he concluded that there was "no valid science whatsoever to suggest the Willingham fire was arson," he testified last week. Willingham's attorney handed that conclusion over to the Navarro County district attorney, the fire marshal, and the Governor's Office, but no one ever contacted him to ask about his assertions, he testified. Hurst said it's impossible to rule out arson altogether, but he saw nothing that would back up that conclusion. Instead, he said, the more likely culprit was faulty, "jerry-rigged" wiring in the room where the children slept: "It was an accident waiting to happen," he said.

The fight over whether Willingham might have been wrongfully convicted and executed has been playing out for several years. The Innocence Project first asked Lentini to review the case in 2006; it was then forwarded to the nascent Forensic Science Commission, which subsequently hired another expert, Craig Beyler, to review the case (his conclusions mirror those of eight other experts who have so far weighed in). Just two days before the commission was set to question Beyler about his conclusions, Perry removed two commissioners, including the group-selected chair, Austin attorney Samuel Bassett; Perry then appointed Williamson County District Attorney John Bradley as the new chair. Bradley has since tried to put the whole matter to bed, drafting a report, intended to close the case, that notably sidestepped the question of whether the Fire Marshal's Office had a duty to acknowledge it might have relied on inaccurate or outdated science – not only in the Willingham case but also in potentially hundreds of other arson cases. The commissioners rejected Bradley's move.

In closing the case last week, White told Baird that the evidence offered against Willingham has been "impugned today by the overwhelming testimony of these experts" who agree that Vasquez's conclusions were "tantamount to some tea leaf reader." He noted that the case's outcome was markedly different than that of the eerily similar arson case against Ernest Willis, who was also sent to death row based on evidence gathered by Vasquez. He was later exonerated after prosecutors reviewed the case based on the work of Hurst, who concluded there was no arson. Willis walked free just months after Willingham was executed. "We have a Willis that walks free today, but we have nothing more than the memory of a Willingham," he said, even though the cases "are nearly identical in facts and law."

For more on the Willingham case, see Frontline's "Death by Fire" episode at www.pbs.org.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.