City to Moriarty: Drop Dead

City declines allowing Bill Moriarty to return to former position with Austin Clean Water Program

By Michael King, Fri., Sept. 7, 2007

Bill Moriarty ain't gettin' his job back.

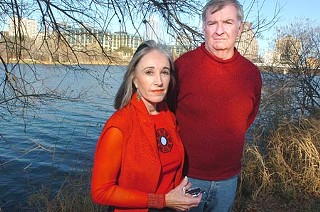

That's the gist of an Aug. 20 letter from city attorney Anne Morgan to Moriarty's attorney, Robert Notzon, in response to Notzon's Aug. 7 letter to City Manager Toby Futrell requesting the city consider enabling Moriarty to return to his former position of program manager of the Austin Clean Water Program. Notzon's letter also asked that the city provide letters of apology and recommendation for former city environmental consultant Diane Hyatt, who lost her contracts with the ACWP when Futrell concluded that Moriarty and Hyatt's personal relationship constituted a conflict of interest. Notzon suggested that since a subsequent investigation by the Office of the City Auditor (as reported by the Statesman in July) had found no wrongdoing and since the city acknowledged that Moriarty had done a fine job, "my clients request that the city take the next logical step of returning them to their previous professional positions." If that can't be done, Notzon continued, he is available to discuss "other options to assist in correcting the harms done to Ms. Hyatt and Mr. Moriarty."

Responded Morgan tersely, "This matter has been fully litigated and finally resolved between the City of Austin and Bill Moriarty." She then continued, "The City does not intend to provide anything further to Ms. Hyatt."

In the spring of 2005, Moriarty was let go as program director by Earth Tech, the general contractor on the ACWP, after the city discovered that Moriarty and Hyatt had become a couple sometime during Moriarty's tenure and that Hyatt's firm, Hyatt and Associates, had been assigned contracts under the program. Moriarty and Hyatt protested, to no avail, that their private relationship began after the contracts were awarded (a chronology still under dispute) and that, in any case, Moriarty had no role in awarding the work – such contracts are granted by the city department supervising the project, in this case Public Works. Futrell was unmoved, insisting that Moriarty had a duty to disclose his relationship with Hyatt and that the consequent conflict of interest – real or perceived – merited Moriarty's removal from the program and the loss of Hyatt's contracts.

By the time the initial dust storm settled, Moriarty had sued Futrell, Assistant City Manager Joe Canales, and Council Member Brewster McCracken for contract interference and defamation. That lawsuit, as Morgan reminded Notzon last week, was eventually settled – one outcome was a city letter for Moriarty's file confirming that the ACWP under Moriarty was "a well run and successful Public Works program." But Morgan reiterated that, despite Moriarty's disagreement, "the City Manager determined that Moriarty had a conflict of interest [concerning Hyatt] that he failed to disclose."

Still very much pending is another lawsuit against numerous major city engineering firms and their representatives, whom Moriarty and Hyatt accuse of collaborating in an illegal effort to persuade the city to remove Moriarty from the ACWP. As Notzon put it in his letter, "In approximately April 2005, several engineering firms, their representatives, and their lobbyists got together and decided to make unsubstantiated and false allegations against Moriarty and Hyatt to [Futrell] in an effort to remove Moriarty from the ACWP." Moriarty has contended that the engineering firms and their associates – including major local players like PBS&J, Malcolm Pirnie, attorney David Armbrust, and former mayor Bruce Todd (among several others) – had been long accustomed to favorable treatment on city contracts and blamed Moriarty for installing performance standards and procedures making them increasingly subject to competition. Indeed, some of them claimed Moriarty had solicited bribes in return for steering contracts in their direction, but separate investigations by both the Austin Police and the Travis Co. district attorney's office have found no evidence of wrongdoing.

Morgan's response to Notzon did not confine itself to rejecting his request for amelioration on behalf of his clients; she also icily accused him of violating state bar rules prohibiting direct contact with a represented defendant (i.e., Futrell) and implicitly threatening litigation. A couple of days later, Notzon replied that he has no plans to sue the city or Futrell and, moreover, that "my letter was merely a glorified request for Mr. Moriarty's and Ms. Hyatt's jobs/contracts back given the fact that they are acknowledged by the City to have not engaged in the conduct for which they were accused and initially removed from their contracts. ... Given your letter, I will assume that the answer is no to both of my clients' requests."

Asked last week about the correspondence, Notzon reiterated that he simply wanted to give the city an opportunity to "decrease the damages" to Moriarty and Hyatt, who have been forced to find other, less-rewarding employment (Moriarty out-of-state) since their removal from the ACWP. Referring wryly to recent disclosures concerning alleged conflicts of interests involving City Manager Futrell herself, Notzon said, "I thought, 'Why not?' Let's give the city a chance to reconsider in light of new understanding of what is considered a 'conflict of interest' or even a 'perceived conflict of interest.' They didn't have to take that position in [Moriarty and Hyatt's] case, and I gave Futrell an opportunity to rectify how conflicts or 'duty to report' have been considered."

City attorney Morgan was out of the office this week and unavailable for comment about her correspondence with Notzon.

The pending civil lawsuit suggests that there will be several more chapters to the Moriarty story. Responding to the city's perhaps unsurprising rejection of help for his clients, Notzon concludes his second letter by requesting that Morgan schedule depositions for Futrell and McCracken in the Moriarty/Hyatt lawsuit against the engineering firms and their associates. Notzon's initial pleadings argue that the defendants illegally, via conspiracy and defamation, induced the city to force the removal of Moriarty and Hyatt from their ACWP contracts. Presumably Futrell and McCracken can shed some light on if, and how, that process came to be.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.