History Still Hidden

Reporter of 'Statesman' racial-cleansing series disowns published version

By Kevin Brass, Fri., March 16, 2007

Nearly a year after the Austin American-Statesman published a gripping four-part series detailing the systematic expulsion of blacks from small communities throughout the South, the author of the series wants nothing to do with the version that made it into print. "I've made many, many mistakes as a reporter, but the one thing I've never done is see a story go into print that I knew was wrong," said Elliot Jaspin, the series' author. "This is the first time that I've seen a story go into print that I knew was wrong."

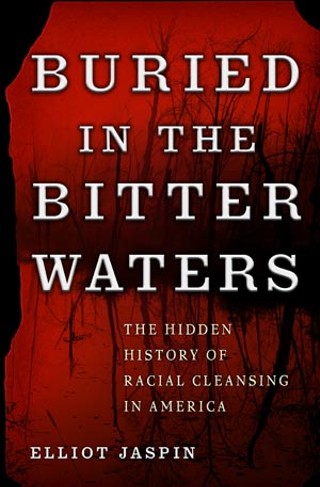

Easily the most ambitious series published by the Statesman in recent memory, "Leave or Die: America's Hidden History of Racial Expulsions" provided exhaustive evidence of what Jaspin terms "racial cleansing" by whites in communities like Comanche County, Texas. In 1886, all the blacks in Comanche were given 10 days to leave or face a lynch mob. As chronicled by Jaspin, Comanche remained almost all-white for more than 100 years. Jaspin, who works for the Washington bureau of Cox Newspapers, owner of the Statesman, spent parts of eight years developing the project, which is also the subject of his book, Buried in the Bitter Waters: The Hidden History of Racial Cleansing in America, released March 12, and a new documentary film.

But Jaspin, 60, who shared a Pulitzer Prize earlier in his career, says the story that ran in the Statesman was "incomplete" and "misleading." Statesman editors and their bosses ignored conflicts of interest and "procedures designed to protect the integrity of the reporting process" when they published the series, he says. In the book, he accuses Statesman editors of undermining the series by removing sections about the coverage of racial unrest in Georgia by the Statesman's sister paper, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Even after the cuts were made by Statesman editors, the Journal-Constitution didn't run a word of Jaspin's series.

From the start, Jaspin believed his story was as much about a cover-up – a white-washing of history – as about historically overt racism. Over and over again he found examples of newspapers playing down or simply ignoring what was happening to black populations. Today he believes the cover-up continues. "When you look at the history of racial cleansing, the thing that comes back that is shocking is how we have refused to acknowledge what took place," he said. "I had to get this absolutely right."

Journal-Constitution editors have responded to Jaspin's accusations by questioning his reporting and arguing that the series – which was good enough for the Statesman – did not meet their requirements. "As we went through the editing process, we had more fundamental questions about selective use of facts and interpretations," said Journal-Constitution Editor Julia Wallace in a statement released to the Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education's Web site. (Wallace did not returns calls.) "This series did not meet our standards because of questions we didn't believe were answered adequately."

Soon after the series ran, Jaspin was demoted. He's been labeled a prima donna and disloyal by some of his peers. "I understand his frustration and his concerns about some of the things that happened," said David Pasztor, the series' editor at the Statesman, who now works for The Texas Observer. "But I think his reaction to them was dramatically over the top." (Statesman Editor Rich Oppel and Managing Editor Fred Zipp did not return repeated calls requesting comment.)

'No Impact'

At first, the Statesman was the project's savior. After years of research, Jaspin couldn't find a newspaper in the Cox chain interested in a story documenting racial cleansing in the United States. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Cox's flagship paper, turned it down twice. "It's a story with no impact," he was told by an AJC editor. There was "nothing new" in his reporting, he was told. Editors implied that he was a "zealot" for pursuing the old stories.

But he found a receptive audience in Statesman Editor Maria Henson. When Henson left a few months later to go to the Sacramento Bee, her replacement, Pasztor, also embraced the project. With Editor Oppel and Managing Editor Zipp enthusiastically on board, the project was a go; October of 2005 was initially targeted for a publication date.

With unusual zeal, the Statesman poured resources into the project. A photographer was sent around the country to illustrate the series. Web designers were assigned to build an interactive educational Web site. "They saw this as a Pulitzer [Prize] contender," Jaspin said.

From the outset, Jaspin told his editors that The Atlanta Journal-Constitution's coverage of Georgia's Forsyth County was a key element of the story. In Jaspin's research, he came across numerous examples of the paper printing what he terms the "fable" of the era, ignoring the horrors of racism for a sanitized version that downplayed the turmoil. In 1987 the AJC published a story referring to the expulsions in Forsyth County as "legend," suggesting instead that many blacks forced from their homes actually sold their land at a profit.

Jaspin knew that writing about the Journal-Constitution would be complicated territory. Jaspin works for the Atlanta-based Cox Newspapers, which operates separately from the Journal-Constitution and the newspapers in the chain. But the bureau depends on support of the individual papers, and the AJC is the biggest, most influential paper in the Cox chain. Nevertheless, there didn't seem to be any question of the worthiness of documenting the role of the Atlanta paper. Even Jaspin's boss at Cox acknowledged the AJC's coverage of Forsyth Co. had been "half-assed." In recent years, several large newspapers, including the Hartford Courant, the Los Angeles Times, and Lexington Herald-Leader, have formally apologized for their coverage of the struggle for civil rights. Early on, the Statesman series was headlined as the "Hidden History of Racial Cleansing" – and for Jaspin, the still "hidden" nature of the history was a central element of the story.

In September 2005, just a few weeks before scheduled publication, with the story edited by the Statesman and set to run, Jaspin was on vacation when he received an urgent call from his Washington bureau chief, Andy Alexander, telling him he needed to be in Austin the next day for a meeting. Editors in Atlanta had "blown a gasket" over the series, he was told.

In a heated discussion with Atlanta editors, Jaspin was forced to defend his characterizations of the paper's coverage. On the face of it, the discussion struck Jaspin as a breach of standard journalism ethics. The AJC was the subject of an investigative story. But the Atlanta editors were not only getting a chance to read the story before publication but, in essence, to approve or disapprove it. It's an arrangement newspapers never offer to story subjects. Normally, when papers write about related companies, the ground rules are clear. "They should treat a sister paper like any other source," said Félix Gutiérrez, professor of journalism at the USC Annenberg School for Communication. But, in this case, the Atlanta paper was also a client of the Washington bureau, which was eager for the chain's flagship paper to run the series.

At first, Statesman editors backed Jaspin's position. "Why are [we] pounding on The Atlanta Journal-Constitution for being apologists who look at race relations in Forsyth County through rose-colored glasses?" Pasztor said at one meeting. "The reason we are doing that is because The Atlanta Journal-Constitution have been apologists who look at the race relations in Forsyth County through rose-colored glasses. It's just true."

Yet, faced with the resistance from Atlanta, Oppel decided to hold the series. Athough initially leery, Jaspin was encouraged when Oppel stood up to an AJC editor, telling him the Atlanta paper didn't have the "moral authority" to argue against the story's conclusions. "It was pretty impressive," Jaspin said. But in a January 2006, meeting, three months after the project was originally scheduled to run, Zipp made it clear he was worried about getting a call from his Atlanta bosses denouncing the series. If that happened, Zipp said, "What I will be required to do is take it out or not publish it."

Generating Euphemisms

Jaspin soon began getting edits from Oppel and Zipp toning down sections about the AJC reporting. When Jaspin complained, Zipp defended the AJC. Perhaps their failure to accurately cover events in Forsyth County was because they "just didn't know what the fuck was going on," he told Jaspin.

Pasztor says there were many attempts to find a compromise, including developing a longer sidebar on media coverage. But Atlanta editors refused to cooperate, he says. "The problem was that the editors from Atlanta ... were just utterly incapable of being intellectually honest about this process," Pasztor said. "They were determined to gut this part out of the series, and they were not willing to engage in any sort of a rational, adult conversation about what was fair and what wasn't fair."

More edits took out details on the Journal-Constitution. In a line that noted the Atlanta paper "incorrectly concluded that most blacks forced from the county were able to sell their land, some at a profit," Oppel took out the word "incorrectly."

The biggest debate ensued over use of the term "racial cleansing." Although Jaspin was adamant that the term was an accurate description of what took place, Cox Newspapers President Jay Smith felt it was too strong and insisted it be changed. "I was appalled," Jaspin writes in the book. "Time and again I had noted the euphemisms that whites had used to hide the reality of what they had done. Driving off your neighbor at gunpoint, for example, was a 'disturbing situation.' Now I was being asked to continue this sorry tradition." In a bit of whimsy, Jaspin developed a "euphemism generator," allowing editors to pick words from different categories to develop a palatable replacement, such as "involuntary African-American relocation." Ultimately, an editor in Austin came up with "racial expulsions." The term "racial cleansing" was cut. In an e-mail to the Chronicle, Smith said, "I felt the word 'cleansing' was akin to genocide. Horrific acts occurred, but I thought the word 'cleansing' overstated the case. I still feel that way."

Jaspin was furious. By removing the proper label and deleting the sections on the Journal-Constitution's coverage, he felt, the series was simply perpetuating the same old myths. "When we were talking about fuzzing Atlanta's role, it was just another example of how we've fuzzed history to avoid facing what is taking place," he said.

Initially he wanted his name removed from the story. He sent a memo to Austin editors, warning that the story was "incomplete and misleading." In his book, Jaspin writes, "In the normal course of things such a memo would raise alarm bells at any newspaper. It did not."

Eventually Jaspin received a final edited version from the Statesman with most of the references to the Journal-Constitution removed. The Statesman slotted it to run in July 2006, nine months late. The Journal-Constitution refused to run it. "In the end, we didn't believe the series answered enough of the questions we raised," said AJC Editor Wallace in her written statement to the Maynard Institute. "Those are the kinds of decisions we make every day on whether to publish stories. To suggest we are afraid of tackling the tough subjects flies in the face of the work we do."

According to Jaspin, Cox Newspapers Washington bureau chief Andy Alexander told him, "I think we both know what's going on here. They are afraid of angering white people." (Alexander doesn't deny making the statement. "I should not have said there were concerns about angering white readers," he said in a written statement to the Maynard Institute. "Often, things are said in the heat of the editing process that are untrue.") "Jaspin didn't like the editing process," Alexander said in his statement. "That's our job as editors, to challenge every fact and theory to see how to best write a story."

Although his bosses envisioned appearances on Oprah and nationwide publicity for the series, Jaspin refused to promote it. He felt it would be hypocritical. Reaction in his office was swift. In the book he writes, "I was, among other things, called an 'idiot,' asked if I wanted to continue working at Cox, and told that, if I felt so strongly about the issue, I should resign." The Statesman threw a party to celebrate the launch of the series; Jaspin wasn't invited. When Oppel wrote a column about the series, he praised the Statesman photographer but said nothing about Jaspin's reporting.

Although Jaspin originally praised the Statesman editors, he leaves no doubt where he stands now. "They caved," he said. "They took the easy way out."

Eyes on the Prize

Pasztor, originally one of Jaspin's biggest supporters, says Jaspin overreacted and acted "like a 13-year-old." There was a real fear that Cox executives would kill the series if the Journal-Constitution section wasn't toned down, he says. "I would not characterize it as caving," he said. "I would say [the Statesman editors] made a practical decision based on a very bad set of circumstances that ultimately resulted in the series getting published." He agrees with Jaspin that the AJC sections should have been in the series. However, "as unfortunate or as offensive as it was that that stuff had to be taken out, the greater good of publishing the rest of the series far outweighs the loss of that part," he said.

When Oppel tried to console him about taking out the term "racial cleansing," Jaspin says he seemed more worried about the chance for the Pulitzer than the ethical issues. "I can tell you what is being discussed here in no way impairs the strength of this in Pulitzer competition from my perspective," said Oppel, who sits on the Pulitzer Prize board.

But Oppel will be disappointed. Jaspin says he has refused to allow the Statesman or Cox to submit the series for awards under his name. If they do and it wins an award, he says he will refuse to accept it. (In fact, the online version of the story won a National Headliner Award last week.) "Even today I'm mortified," Jaspin said, before the award was announced. "To submit [the series] for an award, it's just grotesque. I cannot believe they would be that stupid. It would be embarrassing." ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.