My Semester on the Beat

Wherein our reporter pursues the bad guys, abhors Problem People, studies community policing, and earns a perfect-attendance Koozie in the APD's Citizen Police Academy

By Nora Ankrum, Fri., Dec. 1, 2006

When you imagine a 10-hour ride-along with a cop, there's a lot of stuff you expect – sirens, squealing tires, tense confrontations, handcuffs ... mine began with a dead battery.

I was scheduled to tag along on a 3pm-1am Saturday patrol shift with Officer George Silvio, a friendly, mild-mannered guy in his mid-30s. He jumped the car while I waited in the break room reading the bulletin board. I probably read everything half a dozen times – a Cops for Christ flier, a fatal-shootings stat sheet, a workers' compensation notice, a memo regarding civil-service proceedings appealing Officer Julie Schroeder's indefinite suspension – before Officer Silvio returned. He had us on the road around 4pm; by five, hot on the case of an abandoned Camry in a turn lane, we had a flat tire.

We'd pulled into a parking lot nearby, where two different people helpfully pointed out the flat, and it was there – as a city maintenance truck was arriving to change our tire; a tow truck sat idle, having popped a cable while attempting to fetch the Camry; a second tow truck was backing into the turn lane to try again; and Silvio was directing traffic in his yellow reflective vest, which he'd retrieved, neatly folded, from somewhere behind his seat – that I realized my turn on the mean streets of Austin wouldn't remotely resemble an episode of Cops or even The Wire.

Instead, my day-in-the-life-of-a-lawman would be more like one of those illustrated pages from a Richard Scarry book. Just like Farmer Alfalfa and Grocer Cat, Officer Silvio and his fellow municipal workers were each performing a modest but indispensable service in the intricately connected web of life that is Busytown.

Citizen Ambassadors

It turns out there are people riding around with Austin Police Department cops all the time, from cadets in training to Victim Services Division volunteers to psychology students. There are so many, in fact, that had I not ridden this particular weekend, I'd have had to wait a couple of months before the schedule opened again – the fate of one of my classmates. We were all supposed to ride with an officer the weekend of Aug. 11-12 as part of the Citizen Police Academy, a free course designed by the APD to show regular people what it's like to be a cop. Though few people really know about citizen police academies (or understand them – "Does that mean you can make citizen's arrests?" everyone always asks), they're increasingly popular. About 45% of U.S. police departments offer some kind of CPA, and most of them, like the one APD offers, are structured as once-a-week classes stretching over about 11 weeks.

Some CPAs target specific groups, like senior citizens, teenagers, businesses, or minority communities, but the basic goal is always the same: to create diplomats. CPA graduates go out into the world and tell their friends that the police are really just big cuddly teddy bears – or at least not some species of unthinking blue ogre ready to pounce on the guilty and innocent alike. An added bonus is that graduates tend to advocate for things like better police pay, and some even join alumni societies, which help police departments in all kinds of tangible, cost-saving ways. In Austin, CPA grads volunteer to process crime-scene photos, role-play during training exercises, or drink on APD's dime so that cadets can practice field sobriety testing. They also raise funds for things that don't quite make it into the APD budget. If Forensics needs a new microwave for the kitchen, they call the alumni society.

Most police departments try to spice up the typical lecture-based CPA curriculum with a lot of hands-on activities, which vary from jail tours, CPR certification, and mock trials to driving squad cars, dusting for fingerprints, and even shooting guns. But the one thing every decent CPA seems to have is the momentous, all-roads-lead-here ride-along. Ours fell toward the end of the course, leaving plenty of time for the suspense to build.

Know Your Neighborhood

Every week our instructor, Senior Officer Joe Muñoz, would give us a new piece of cryptic advice, like, "If your officer gets in trouble, it's your choice whether you want to get out and help." He followed this tip with the story of a man who'd stayed in the car while his officer got pummeled (and whose classmates wouldn't let him live it down), and a woman who'd done the opposite (and had gotten arrested in the ensuing confusion). We were advised not to bring anything along that couldn't be tied down, giving me visions of being impaled by a water bottle. Muñoz warned us not to be chatty, smelly, or intoxicated. More than once, he reminded us: "You might be too busy to eat."

We returned to class after our ride-alongs giddy with stories. Matt got to bust up a party. Thomas was hailed by a man whose girlfriend was puking in his new Lexus. Charlene told the class that she was called to a disturbance in Acting Chief Cathy Ellison's apartment complex, to which Muñoz responded, "Chief Ellison lives in an apartment?" Carolyn by far had the best time. In one day, she saw a dead cow in a median, a security guard who'd shot himself in the butt, and a young Target shoplifter who, having been handcuffed, kept asking, "Can y'all pull my shorts down so my underwear will show?"

The lightheartedness of a lot of my classmates' stories testifies to how safe Austin really is. We're the fourth safest city in the U.S., based on FBI statistics for violent crime, and according to Assistant Chief Charlie Ortiz, we in large part have APD's community policing program to thank for it. "Community policing" – like "new urbanism" or "attachment parenting" – is the kind of catchphrase that gets thrown around a lot in conversations about reform. It reflects a shift away from reactionary policing (an unfortunate byproduct of the 911 system) and toward addressing the root causes of crime. Community policing requires police to have working relationships with the people living in a neighborhood rather than just driving through it with the windows rolled up. Programs that reflect this philosophy (like the Citizen Police Academy) became popular recipients of federal money in the Nineties thanks to the creation of the U.S. Department of Justice's Community Oriented Policing Services Office, but APD was an early adopter of the philosophy. Our CPA began in January 1987, placing it among the oldest in the country, and to this day it's been fully funded from within the department.

The People Business

Until I joined the academy, I had never heard of community policing. We didn't actually hear the phrase in class all that often, either. (The most notable exception came from a police academy instructor who said, "We work hard to get away from the military model of policing. Community policing is the antithesis of that – it's about problem-solving, and you can't do that if you need someone to tell you what to do.") Our class manual, however, provides a detailed history of the philosophy, from its origins in a 1979 article written by Herman Goldstein (which was expanded into the 1990 book Problem-Oriented Policing) to its bumpy implementation in Austin, which required sweeping and controversial organizational changes, including the elimination of the highest promotable rank, a move meant to force more independent decision-making down through the lower levels.

This history helps explain the emphasis in our lectures on "problem solving" and "discretionary decision-making." It seemed to be on everyone's mind, from the 21-year-old police officer fresh off his first shift – who told us, "I might handle a situation differently than another officer, but it'll still be right. I don't know if I could be a cop if somebody just told me, 'Okay, write this guy a ticket'" – to lecturer Sgt. Keith Stoddard, who pointed out that a person speeding down the road could turn out to have a kid in the back seat having an asthma attack. "No one wants an officer not to consider the circumstance," he said. Even Charlie Ortiz's explanation of the department's pursuit policy reflects this shift in thinking: "Pursuits [used to be] undisciplined relative to today," he said. Now, the stakes have to be pretty high to warrant the risks of a high-speed chase. Before, Ortiz said, "We would chase people for the most minor traffic violation. We'd chase 'em till the wheels fell off."

This notion of discretionary thinking relies heavily on the other pillar of community policing, which is community involvement. In order to use discretion in determining, for instance, how loud a party has to be before it surpasses the acceptable norm for a particular neighborhood, an officer has to be familiar with that neighborhood. A community-based, preventative approach to policing also highlights how reliant the police are on citizens just doing the simplest things like reporting suspicious behavior. The lesson that has stuck with me from our Sex Crimes lecture was the importance of reporting flashers, something I'd never have done before – nakedness seems harmless enough, right? But if investigators can pull a DNA sample from the scene, they can enter it into the CODIS (the Combined DNA Index System) and potentially pull up a match for a rape or other serious offense. I suppose it's because of this reliance on the community that our lectures were filled with phrases like "waiting tables is the single best job for preparing to be a police officer" and "We're in the people business. If you don't like people, then you're in the wrong business."

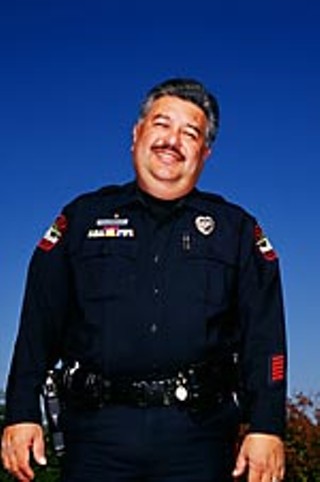

While undeniably image-conscious, this attitude still helped chip away at the bully image that cops have; our instructor, Officer Muñoz, with his gentle demeanor and slight Santa belly, didn't hurt either. He embodied that mix of humor, sweetness, and sternness you learn to expect from the police as a child – and quickly forget as a teenager, the first time a cop speaks to you like you're a criminal apparently because you've gone through puberty. A 29-year law-enforcement veteran who's received Officer of the Year accolades from three different organizations, Muñoz was clearly excited to watch us learn the ins and outs of policing. He'd stand at the back of the classroom grinning and prodding the speakers: "Have someone put on the vest," or "Tell 'em about what happened last week." He was often fussing with his computer so he could play videos for the class – he liked making us laugh with scenes from Cops or Reno 911!

Problem People

Every member of our class had passed a background check to get into the academy, and we were required to wear name-tags at all times, lest we wander unsolicited into other parts of the building – not that we could, as we needed an escort each week to enter the building at all and to allow us, with a special security card at the elevator, up to the fourth floor. This weekly ritual started us off with a strong sense of our privileged status but also our boundaries: We were civilians; they were police. Muñoz's enthusiasm counterbalanced this rigidity and offset his own school-marm tendencies, clearly honed during the 10 years he's spent fine-tuning the academy. He kept us in line with a meticulously arranged classroom that included assigned seating and nameplates printed with the CPA logo. He charged our class president, Kari Terrell, with the honor of alphabetizing the nameplates every week after class.

His sensibility was most embodied in the "Types of Problem People" handout he reviewed on our first day, which listed all the possible ways we, as students, could annoy him. From the Loudmouth to the Latecomer, the Broken Record ("they keep bringing up the same point over and over again") to the Interpreter ("always speaks for other people") to my favorite, the Headshaker (who "nonverbally disagrees in a dramatic and disruptive manner"), Officer Muñoz left little room for schoolroom mischief.

Of course, we weren't a group particularly inclined to be rowdy or disagreeable. I wasn't sure exactly what type of person would attend a CPA, spending four hours every Tuesday evening learning about police procedure, but it turned out not to be a bunch of crazies obsessed with putting lawbreakers behind bars. Instead it was a mix, with ages ranging from late teens to mid-60s, of police officers' family members, criminal-justice students or people planning to go into law enforcement, people who deal with the police in their occupations (such as Anita, a facility investigator with the state Department of Family and Protective Services, and Sam, a college student considering a career in politics), and, yes, a few curious citizens, like Carolyn, a bubbly redhead who joked that she'd heard APD officers were cute – to which Muñoz responded, "There have been some weddings out of this. I don't wanna lie." Also included in our ranks were members of the Citizen Review Panel, for whom the class is required.

The CRP is one of the bodies that review citizen complaints against APD or its employees; it shows up in the press whenever there's a high-profile case like last year's shooting of Daniel Rocha by Officer Julie Schroeder. Initially, complaints are investigated by the Office of the Police Monitor, but if the chief of police doesn't sustain the complaint at that point, then either the OPM or the complainant can refer it to the CRP. One of our CRP members was Dick Neavel, a retired scientific adviser from ExxonMobil, who stood out as a tougher sell than most. He maintained a skeptical presence and diligently took notes with one of the green pens we'd all been given on the first day – having lost mine early on, I couldn't help noticing that he was still using his during our last lecture. He asked devil's advocate questions in a class more often characterized by the empathetic or the purely curious. I heard him give a stern "thank you, sir" a couple of times to speakers whose lectures he particularly appreciated. The only student tougher than Dick was Anita Overton.

One of two African-Americans in the class, Anita asked the most vigilant questions, always with an eye toward the underdog. Assistant Police Chief Charlie Ortiz was a last-minute replacement speaker for Chief Ellison one evening, and without a prepared lecture he opened up the floor for general questioning. Topics ranged from what kinds of engines squad cars have to how patrol officers remember the hundreds of city ordinances they're expected to enforce. Then Anita raised her hand. "In the wake of the Sophia King, Jesse Lee Owens, and Daniel Rocha shootings," she said, "it appears that tensions within the African-American and Hispanic communities have increased. What is APD currently doing, and what is the long-term plan to specifically address and perhaps reduce some of those tensions?" (You can probably guess that Ortiz chose an answer straight from the community-policing playbook; the incidents called for a "renewed relationship" with the communities where the shootings happened, he said.)

Anita also spoke up when she disagreed with a speaker, as when Sgt. Stoddard argued against the idea that the Rodney King beating was "punitive." The officers were using the "weakest strike" police are trained to use, he explained, and it's meant to subdue a person. But when King kept trying to get up, they just kept hitting him rather than switching tactics – an example of what happens when police aren't trained to use discretionary thinking. It was a particularly long and complicated explanation, and when he finished, the room was silent for a moment before Anita raised her hand and said what was probably rattling around in most people's minds: "I'm already having trouble with this session. ... I don't see how it could take 81 strikes to subdue him."

Anita has said since then that she was happy with how the speakers took on our questions. "I was impressed and pleasantly surprised by the fact that each appeared sincere and genuine in their responses," she wrote to me in an e-mail. "I never got the feeling ... anyone was trying to be evasive or cover up any wrongdoing or misdeeds." Despite her biggest reservation about the CPA – the fact that there were no African-Americans represented among the many people who spoke to our class (that's not the case every semester) – she says that overall it was a wonderful experience. She feels that it rekindled her respect and admiration for the police – an endorsement that represents precisely the kind of attitude CPAs are designed to promote.

Commencement

At graduation, we wore our "Sunday best," and we stood for our class picture with the tallest person standing in the middle of the back row, and the rest of us cascading down- and outward from there. Cathy Ellison and City Manager Toby Futrell were scheduled for the program, but an emergency called them both away, leaving us once again with kindly Assistant Chief Charlie Ortiz, who once again opened up the floor for questions. No one had any, not even the few significant others who came to watch the proceedings. The CPA alumni were there with punch and cake and a merch table full of CPA T-shirts, jackets, and teddy bears. Our class president gave a speech, and we each had our picture taken as we received our graduation certificates, commemorative police patches, and navy blue CPA mugs. Those of us with perfect attendance were rewarded with CPA Koozies.

Taking the class, I've realized, really was like being a kid again. It was a return to the days when policemen smiled at you, eager to let you pet the K9, and firemen wanted to give you rides in their truck. It's not hard to imagine why people go on to join the alumni society, where they can take once-a-month ride-alongs and see real-life autopsies and attend conventions where they hobnob with fancy FBI investigators. I've simply returned to the name-tagless anonymity of the civilian world, where the only police I'm likely to rub elbows with are the kind who want to see my license and registration. But even this workaday place has been painted in bright new Richard Scarry colors, because regardless of what I think about cops, I have a much better idea of what it means to be a citizen – and I have a Koozie to prove it. ![]()

For more on Nora's experiences in the CPA classes, see "School Days," below. For information on applying to the academy, go to www.ci.austin.tx.us/police/cpa.htm.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.