Save as We Pave?

Travis County hopes 'conservation development' can limit polluting sprawl

By Katherine Gregor, Fri., Oct. 20, 2006

Imagine a beautiful piece of land along the Pedernales River. Should it become a nature conservatory, preserved in perpetuity (on the public nickel, with common public access) to protect open space, fragile ecosystems, watersheds, and the rural character of Texas? Or should it be privately developed as a residential subdivision, a green-building neighborhood where nature-loving residents can enjoy country living but still drive into town in their SUVs every day? What if one 500-acre ranch could become both – letting us have our natural open space and build on it, too?

That's the contradictory but intriguing proposition offered by "conservation development," a national movement now taking shape as a proposed new voluntary program to be defined by Travis County ordinance. If it's adopted – to be considered again by the Commissioners Court on Oct. 24 – Travis Co. will become the first in Texas to adopt the conceptually progressive land-use approach. While eligible local properties here are limited, the county's leadership could well influence counties statewide and result in significant land conservation.

As the name suggests, a conservation development combines two elements – 1) protected open space and 2) housing – on a single, large, undeveloped tract, generally in a rural, unincorporated area. Homes, roads, and infrastructure are clustered, allowing at least half of the land (the acreage with the most sensitive ecological and natural features) to be protected in perpetuity. Ideally, the land conserved is linked to other open spaces, protecting wildlife corridors and complete ecosystems.

In areas where urban-fringe growth threatens to rapidly overtake most of the open land – as in outlying Travis Co., west and east, and the surrounding Hill Country and Blackland Prairie – conservation development, in theory, provides a middle-ground solution that holds broad-based appeal. Therein lies its political power. Longtime farming and ranching families get to preserve traditional values, their rural heritage, and wide open spaces. Developers get a voluntary approach that can yield about the same profits as a conventional 5-acre-lot subdivision, provides a distinctive marketing angle, and lets them be good guys for a change. Responsible-growth advocates (formerly known as environmentalists) like it as a way to slow suburbanization, encourage "greener" development, preserve natural beauty, and protect local ecosystems and habitats.

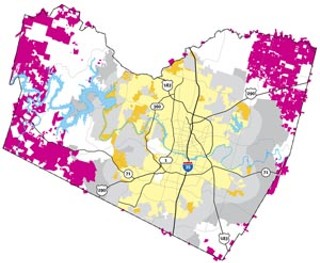

Over the Edwards Aquifer, however, the environmental virtues of conservation development become muddier waters. The long-term pollution generated by a 1,000-home subdivision is sizable (especially when its residents commute long miles on widened highways) whether those houses are built on 1,000 acres or, as with a 50-50 conservation development, on a 2,000-acre tract. The unique porous limestone geology of our aquifer makes it particularly susceptible to contamination from rainwater runoff polluted by the chemical crud that any sort of development brings – spilled motor oil and gasoline, lawn fertilizers and pesticides – including a catastrophic spill. The Edwards Aquifer provides about 5% of Austin's drinking water, and nearly all of San Antonio's. Aquifer recharge, contributing, and artesian zones run right through Travis Co.

Problematically, the term "conservation development" lacks a precise, consensus definition, and it has been applied to projects with wildly varying densities and ratios of preserved land. Last year Dripping Springs adopted a conservation development ordinance (CDO) that requires just 40% of the land to be preserved (Travis Co.'s draft ordinance calls for 50%). The first proposed development under the Dripping Springs CDO, Scenic Greens, would put about 900 houses on 676 acres of former ranchland, on a 1,500-acre tract. But according to adjoining landowner Mark Blakely, local residents are horrified by variances to environmental requirements recently granted to Scenic Greens developer James Kerby – diluting water-quality and sewage-treatment rules in ways that will result in pollution of creeks, drinking water, and Barton Springs.

Also in Hays Co., the Headwaters at Barton Creek – described as a conservation development by Austin developers Terry Mitchell and Dick Rathgeber – is planned to have 1,000 houses on a 1,500-acre tract; about 70% of the land is to become a preserve. Belterra on U.S. 290 (just east of Dripping Springs) once claimed the term but intends to put 1,600 houses on 1,600 acres.

"It's too many homes over the aquifer," argues Colin Clark of the Save Our Springs Alliance, which has expressed only limited support for the conservation approach. Clark, who participated in the 2004-2006 Southwest Travis County Growth Dialog Process that spawned the new ordinance, asks the multimillion-dollar question: Does conservation development provide "greenwashing" for large subdivision developments that don't belong over the aquifer at all?

Carrots and Sticks

The rapid suburbanization and increasing growth pressures in rural Travis County are the real issues driving the Travis Co. Conservation Development Ordinance. For residents of Southwest Travis Co., the need for a better approach to subdivision development was crystallized by residents' concern over environmentally dubious projects – West Cypress Hills on Lick Creek and later a stink over Sweetwater. That led to the Growth Dialog, and new interim subdivision rules that include water-quality provisions. When Steve Windhager of the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center made a presentation to the Growth Dialog stakeholder group on conservation development (at the invitation of facilitator Joe Lessard, now writing the Travis Co. ordinance), the concept had strong appeal to the group, according to participant Christy Muse, an area resident who sits on the board of the Hill Country Conservancy and directs the Hill Country Alliance. HCA supports conservation development as part of its advocacy for regional planning and responsible growth. (Sweetwater's Growth Dialog representative, Rick Wheeler, dissented from the group's final report, stating that the county should not attempt to regulate subdvisions at all.)

For a larger map click here

In crafting, testing, shopping, writing (and rewriting) the new ordinance for Travis Co., consultant Lessard draws on experience as a land developer, a 1989-98 stint as assistant Austin city manager, and service on the citizen advisory committee for the Balcones Canyonland Conservation Plan. He explained that to preserve rural character, counties in Texas typically require a 5-acre lot for each home site. A 100-acre family ranch sold and developed in outlying Travis Co., for example, conventionally would be subdivided into a grid of 20 home sites. But in a conservation development, the same 20 homes might be clustered along one winding country road on only 40 acres – leaving the remaining 60 acres protected as a natural open space – generally allowing access only to property owners or conservation professionals. The problem is, the rules now on the books don't allow for small individual home sites and infrastructure changes without variances, which are rarely granted – which is why a new county ordinance is needed. The CDO basically changes the standards so that developments done under it require no variances.

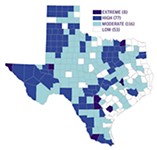

A map of the sites to which the proposed Travis Co. ordinance could apply – tracts with existing agricultural property-tax exemptions, in unincorporated areas outside any city's ETJ (extraterritorial jurisdiction) – shows them to be heavily clustered along the southwest, western, and northeast edges of the county. (The city of Austin could well extend the program to the ETJ areas it controls; initially, however, while the county builds buy-in with more conservative rural residents, it prefers to avoid Austin's liberal taint.) The county has identified about 1,667 properties of 4 acres or more that fit the criteria, although it may set a higher 20-acre minimum to coincide with state requirements for agricultural/wildlife tax exemptions. In practice, the county initially would hope to see conservation development tried on a select handful of large tracts with features of special ecological value.

In Texas, counties historically have lacked regulatory power over development. In drafting a conservation development ordinance, Travis Co. is leading the state in actively using the powers conferred by Senate Bill 873, which in 2001 gave 30 Texas counties new, limited powers to regulate subdivision features. (While zoning, height, and certain types of density limitations are specifically prohibited by SB 873, Travis Co. already has interpreted it assertively in other groundbreaking ways – for example, in requiring developers to dedicate or pay for parkland and to leave 100-year floodplains in their natural state.) "They're doing the best they can, with the tools they have, which are minimal," commented Mary Sanger of Environmental Defense, another stakeholder participant in the Growth Dialog.

Many observers believe the state should grant fast-growing counties like Travis more power to shape rural growth – powers allowed to counties in nearly every other state. In this camp is Valinda Bolton, the Democratic candidate in the closely watched race for Texas House District 47, which runs from the Travis Co. line into Austin. "I'm encouraged by the steps that the county is taking with the conservation ordinance," said Bolton. "Since unincorporated areas in counties are where we are currently experiencing most of our growth and development, it's crucial that counties be able to make decisions that affect them." (Republican candidate Bill Welch did not return a call requesting comment.)

With precious few regulatory sticks, Travis Co. must dangle carrots. Incentives are the name of the game. The proposed ordinance (in its 15th draft at this writing, and certain to undergo more revision) defines a fully voluntary program. The "green" ordinance defines key minimum standards for not only open space and subdivision design but also for energy, water, and materials conservation. Developers who comply with its requirements (see "What the Ordinance Says," p.40) are rewarded in ways that make their projects smoother and more economically feasible. Proposed incentives include lump-sum and ongoing payments, an expedited development-application process, fee reimbursements, exemption from other parkland-dedication requirements, and tax abatements.

Under the CDO, the only specific restraint on individual lot sizes would be for projects with on-site sewage. Where homes require septic systems, existing regulations require at least a 1-acre lot per dwelling unit. Mitch Wright, Regional Issues Committee chair for the Real Estate Council of Austin, spoke at the September hearing to express doubts as to whether this constraint can deliver the "equal yield" densities and profits that developers who are not already committed conservationists are likely to demand. Currently, state rules prevent the use of cluster septic systems serving five or more homes, which would be needed to achieve more tightly clustered homes.

The balancing act in writing the ordinance, of course, lies in identifying exactly how much needs to be given – and gained – on each side to make a program workable. If the voluntary program is ignored by property owners and developers, the CDO won't preserve any land. To work, the incentives need to yield about equal value. Nationally, conservation development has worked best for a high-end, niche market. Conservation development will be embraced by production builders only if it can return profits comparable to those from a conventional subdivision. Or as Joe Gieselman, the county staffer overseeing the ordinance, succinctly put it: "If you can't make money on it, it ain't going anywhere."

"What tears developers up is uncertainty," explained Gieselman. "The ordinance provides assurances and consistency and provides incentives that save the developer money and time." As executive manager at the county's Department of Transportation and Natural Resources, Gieselman is charged with shepherding and eventually administering the ordinance. He speaks of conservation development with a quiet sense of advocacy, hoping that it can succeed as a tool for preserving ecologically valuable Travis Co. land. "Our focus to date is on getting the pioneers through the process," he said. "If the first conservation developments fail, the whole idea could fail."

Policy and Politics

In terms of setting the policy, it's ultimately up to the Travis Co. Commissioners Court – Commissioners Gerald Daugherty, Ron Davis, Karen Sonleitner, and Margaret Gómez, and County Judge Sam Biscoe – to decide whether to adopt the ordinance, and to define the terms of its administration. The court held its first public hearing on the proposed ordinance Sept. 26. Prior to that meeting, Precinct 3 Commissioner Daugherty, who organized the Southwest Travis Co. Growth Dialog, expressed doubts about whether the incentives for developers were sufficient.

"I'm all for trying to develop the Hill Country as sensitively as we can – despite what people say about me," said Daugherty, referring to his prominent reputation as an advocate of highways. "But I don't think the ordinance is going to have much appeal, the way it's set up right now. I fear it may not be enticing enough. There's a real fine line there, in what you're trying to accomplish. You can't ask for too much from the developer. Or on the other side, if you give too much away, you just make a mockery of the deal.

"If you can't get somebody to do it with this plan, then how much sweetening do you have to do?" he asked. "It's kind of like being on a seesaw. And the more it tilts, one way or the other, somebody is not happy."

The cost of the program is also a key concern. "The Commissioners Court is very cautious about providing incentives," explained Gieselman. "They worry about unintended consequences, and they're very conservative with the public treasury – it's their job." As he framed their perspective: "How do you cap the exposure, so as not to drain the county treasury without a positive outcome?"

To address that concern, Gieselman and his staff (working with consultant Lessard) have proposed the incentives as a pilot program initially limited to five properties and five years. The staff has done some number crunching, based on the incentives defined in Draft 15. If applied to the county's five largest eligible parcels, the program could conserve more than 7,400 acres at a total cost to the county of more than $7.1 million – about $960 an acre. If applied to five average-sized parcels, the program would conserve only about 166 acres at a cost of about $201,000 – just more than $1,200 an acre. Either way, it offers a relatively inexpensive way to secure open space. By comparison, over the past decade Travis Co. has paid between $5,000 and $13,000 an acre to acquire parkland.

Land conservation also offers preemptive long-term cost savings for taxpayers. Discouraging a mass exodus to long-commute living is one way of avoiding increased costs for expanded roads, water, and wastewater services. Limiting rural subdivisions also limits costs for services such as schools, fire protection, law enforcement. While the conventional wisdom is that development pays for itself, statistics cited at the Wildflower Center's symposium on conservation development showed that suburban development actually costs the public sector far more than it yields in tax income. As land-uses go, nature preserves are not just pretty – they're a pretty cheap deal.

Precinct 1 Commissioner Ron Davis – whose precinct includes the Blackland Prairie agricultural land in far eastern Travis Co. – pointed out that conservation development is less familiar there than in the southwest region. "I want to wait and see what my constituents are saying," said Davis, who in September saw a vote on the ordinance as premature. "Staff need to go and have several community meetings, with a whole bunch of farmland belt folks out there, and report back to me, as to whether they're in agreement." At the Sept. 26 meeting, a representative of the Native Prairies Association of Texas praised the ordinance and its potential positive impact on eastern Travis Co., recommending that wording be added to encourage restoration of native Blackland Prairie grasslands. Agricultural land also could be conserved as is, with a working farm or ranch left in place.

Citing the complexity of the ordinance, Davis foresaw a slow move to adoption: "We're going to have to spoon-feed this thing very slowly and very carefully." He added, "I have been a very strong advocate of not constructing on the aquifer – that water-quality zone is very precious to me and needs to be protected." Like others, he expressed uncertainty about how conservation developments might impact the aquifer, saying: "It depends on how this thing shakes and bakes."

An Inconvenient Aquifer

Advocates of conservation development in Austin and nationwide tend to be passionate about saving not just one tract of land, but the Earth. Areas prioritized for preservation are identified early on in an ecological assessment – on any environmentalist's short list, these would include sensitive wildlife habitat, native plant landscapes and grasslands, bluffs and caves, water quality recharge areas, and land-adjoining creeks, rivers, or springs. Conservation easements, which run with the land under the supervision of a homeowner's association or a nonprofit entity such as a land trust, ensure that the land will remain undeveloped.

But here in Travis Co. within the Edwards Aquifer recharge and contributing zones, does conservation development offer adequate environmental protection? SOS' Colin Clark would prefer to see the county use public monies – including bonds – to buy environmentally sensitive land outright, even at market rate. Conservation easements allowing just a few homes could be put on the land, which then could be resold to recoup much of the investment. (The city of Austin has tried this approach for water quality protection, with qualified success.) Much as Austin, with the 1992 SOS Ordinance, allocated some $40 million in bonds to establish conservation preserves on more than 5,000 acres in the watershed, the county could do the same. Ultimately, says Clark, locking up undeveloped property would save the county money by eliminating the need to build expensive roads and other infrastructure.

On its Web site, SOS states: "True conservation development for the Hill Country consists of extremely low-density (i.e. one house per 40 acres or lower density) development that ... does not depend [on] central water or sewer or road expansions." By that definition, "Conservation development is an exciting way for the private business community to invest in the Edwards Aquifer watershed." One house per 40 acres, however, is worlds away from the 1,000 houses clustered on 366 acres (with about 1,000 adjoining acres preserved as parkland) planned for Headwaters of Barton Creek. It's also a far cry from the densities likely for projects executed under the proposed Travis Co. ordinance. Gieselman estimates that a project done under the CDO would have just 20% to 40% fewer dwelling units than a standard subdivision.

To ride on a motorcycle back to downtown Austin from Johnson City's conservation development, the Preserve at Walnut Springs (at 66 homes on 2,030 acres, an SOS favorite), is to see with fresh eyes how fast Travis Co. transitions from rural to urban. For a while the bike travels a winding back road through lovely Hill Country, passing just the isolated ranch house. But soon after crossing the county line, the gated entrances and real estate signs for "estate lot homesteads" start popping up. Then a gas station, then the first strip shopping mall, then a conventional subdivision of sardine-packed beige houses. By the time the bike passes an "Edwards Aquifer Recharge Zone" sign in late summer, Austin's urban "heat island" effect is no abstraction – the radiant heat off Loop 1 sears every inch of exposed skin as the motorcycle crawls slowly through traffic. Minutes later, it's back to the high-rise skyline of our fair "green" city, where the chamber of commerce enthusiastically markets greenbelts and Barton Springs as lifestyle amenities, the better to lure the next Samsung.

Urban density is all well and good. But most of us like knowing that the natural beauty of Central Texas is still close by, inside the Travis Co. line. If conservation development can secure at least some of that beautiful land for us, and for our kids and their grandchildren, then the ordinance probably deserves all the support – and scrutiny – the community can bring to bear. Ultimately, its value lies in removing regulatory and economic obstacles for landowners and developers who love the land – and who are already committed conservationists seeking to preserve it. What the county will need to protect carefully against is misuse by profit-driven developers who lack the same passion. To do this kind of project right, you've got to have a conservation heart. ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.