Bringing the War Home

No More Victims works for peace, one wounded child at a time

By Emily Pyle, Fri., Dec. 30, 2005

At the time of this writing, 2,157 Americans have died since the U.S. invasion of Iraq in March 2003. The number of Iraqis dead and injured, though undoubtedly much higher, is unknown. In fact, although President Bush recently offered an estimate of 30,000, both U.S. and Iraqi authorities have gone to considerable lengths to keep the precise number a mystery. In December of 2004, the Iraqi Health Ministry announced that it would no longer keep a tally of civilian deaths or injuries. Iraq Body Count, a London-based organization that bases its count on confirmed online media and eyewitness accounts, estimates between 27,500 and 31,000 dead, "resulting directly from military action by the USA and its allies." The IBC also acknowledges, however, that its count is by definition low, since only confirmed and reported casualties are included. Although IBC doesn't have the resources to know for certain, the organization gave an estimate of 42,000 wounded in a report issued last summer. Late last year, British medical journal The Lancet published a study broadly estimating 100,000 excess Iraqi deaths since the war began in 2003, most of those attributable to the U.S. air war. (See "The Iraqi Toll," p.29.) About one in 10 casualties is a child under the age of 18.

"We're very sheltered over here from the real consequences of what's going on," says Austin-based documentary photographer Alan Pogue, who has traveled to Iraq several times, before and after the invasion. Pogue is co-founder, along with L.A.-based freelance writer Cole Miller, of No More Victims, a nonprofit project which aims, quite literally, to bring the consequences of the war home. Since March 2003, Pogue and Miller have brought three Iraqi children harmed by U.S. military activity back to the United States for medical care. They hope soon to be bringing more. "The American public is odd," Pogue says. "They seem to lack the imagination to know that you can't indiscriminately bomb civilian areas without hurting civilians. I would like people to be confronted with the consequences of what's going on."

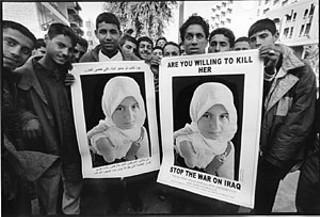

The project began with one Iraqi girl Pogue photographed on a bus in a tiny village in March 2000. Her right arm was an amputated stump, and Pogue knew she had been injured in a U.S. air strike. Pogue, who was in Iraq as a member of a Veterans for Peace effort to rebuild a water treatment plant, snapped the girl's picture. For then, that was that.

Two years later, during the buildup to the invasion of Iraq, Cole Miller was looking for photographs to make a poster protesting the war. He contacted Pogue, whose photographs he had seen online. Pogue sent him the picture of the girl. It was perfect. Miller's poster, which read, "Are you willing to kill her to get to Saddam?" was downloaded from his Web site tens of thousands of times, in nine different languages, and used in anti-war demonstrations all over the world. It's not hard to see why. The girl's eyes in the photograph draw you in.

Medical Sanctions

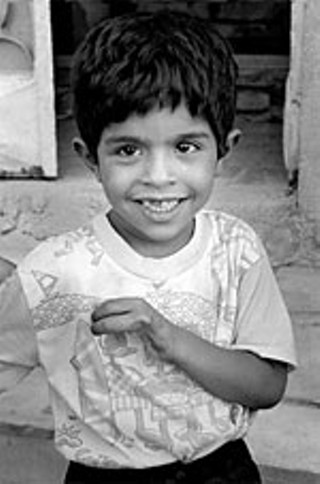

The picture haunted both Pogue and Miller, who became friends. They started to ask each other if it would be possible to learn the girl's name, find her, do something for her. Later that year, Pogue returned to Iraq and, with the help of Iraqi contacts, learned that the girl's name was Asra'a Amir Mizyad, and that she lived in the small village of Abu Floos. He also heard more of her story. Asra'a lost her arm when she was nine, in a 1999 U.S. missile attack that inexplicably targeted her small village as she was walking home from school. Pogue researched military and press accounts of the incident and discovered that the same plane fired another missile that morning, in nearby Basra. Two young brothers, Haider and Mostafa Dinar, were struck by the blast while walking to the candy store. Haider died. Six-year-old Mostafa lived, but his left hand was mangled, and several scraps of shrapnel lodged in his body, including one large piece near his spine that doctors were afraid to remove.

Pogue and Miller contacted the families of Asra'a and Mostafa and began making plans to bring them to the U.S. for medical care. The Iraqi health care system – badly weakened by a decade of U.S. economic sanctions that limited access to basic medical supplies – was struggling to cope with the victims of the latest war. Bandages, painkillers, even bags to hold donated blood were at a premium. There was no prosthetics plant in the country capable of restoring Mostafa's hand or Asra'a's arm. "If their families had been able to get care for them," Pogue says, "there was no care to get." Pogue and Miller started making plans to get U.S. medical visas for Mostafa, Asra'a, and their families.

Meanwhile, the clock was running down as a U.S. invasion of Iraq became more and more of a certainty. In March 2003, Pogue and Miller flew to Amman, Jordan. The timing of the trip was terrible. As the invasion began, the bureaucratic maneuvering required to obtain medical visas to the U.S. became ever more intricate, and the two were running out of money. In the end, Mostafa and his mother were able to fly to Los Angeles where he received surgery to remove the shrapnel from his body, a prosthetic glove to cover his damaged hand, and post-traumatic counseling. Asra'a and her father had to be left behind in Iraq.

It was more than a year before they could return for her. Pogue and Miller flew to Kuwait City in September 2004. They had since received support in the U.S. Congress from Austin Rep. Lloyd Doggett and California Sen. Barbara Boxer, who called the embassy to press for visas to be extended to Asra'a and her father, Abdulameir Salman. It took five weeks for the paperwork to come through, but finally Pogue and Miller were able to bring Asra'a and Abdulameir to Houston, where Asra'a would be fitted for a prosthetic arm and taught to use it, pro bono, at the Shriners Hospital for Children.

Saving the World

With Asra'a and Mostafa cared for, Pogue and Miller believed their work had just begun. They started looking for records of other children injured by U.S. military actions, but medical records for civilian casualties proved elusive. According to Pogue, some Iraqi doctors say they've been ordered by the largely U.S.-controlled Iraq Health Ministry not to release such records. At one point, Pogue and Miller contacted several doctors through nonprofit Save the Children, which was collecting injured children's medical records. Their contacts agreed to send them medical records for more than 70 children, along with photos and contact information. Then, abruptly, Miller received an e-mail saying that the records available probably didn't match his requirements. Medical records for six children did eventually arrive, all for children with congenital heart defects. "There's been a tremendous effort to suppress this information," Pogue says, "to just pretend that this isn't happening, that no civilians have been hurt."

Eventually, Pogue and Miller found other sources – which, for obvious reasons, they prefer not to disclose – with access to medical records of children harmed by U.S. military actions. They began posting photos of the victims, and descriptions of the injuries, to the No More Victims Web site. "The idea was, we'll get something started and then it will spread," Pogue says. "We'll go back a few times, we'll bring some of them out, and then it will be your turn."

That plan is starting to bear fruit. Ashley Severance, a 22-year-old law student in Orlando, Florida, found the No More Victims Web site and the photos and descriptions of the injuries of 3-year-old Alaa' Khalid Hamdan. Alaa' was wounded when a U.S. tank shell blew through the wall of her home and exploded while she was playing with her brothers and cousins. Alaa's father, Khalid Hamdan Abd, came home to find their bodies buried in rubble. Alaa's two brothers were dead, along with three of her cousins. Khalid rushed his daughter to the hospital, where doctors were so certain she would die that they were reluctant to use their scarce supply of bandages on her wounds. Giving in to Khalid's pleading, doctors removed hundreds of shards of shrapnel from Alaa's body and stitched her intestines back together. Against all expectations, Alaa' lived. However, doctors didn't have the delicate instruments required to remove the shrapnel from Alaa's eyes, leaving her almost blind. Moreover, the hasty stitching of her abdominal wounds left her with a massive hernia, as her organs bulged through her incompletely joined abdominal wall.

Severance started making phone calls and found a doctor and hospital who would provide care for free. Alaa and Khalid flew to Orlando in November. This month, Alaa' has had six surgeries on her eyes. While sight in her right eye may never be restored, doctors are very hopeful that her left eye will see again. An operation to reattach her left retina appears to have been successful. Last week, when Khalid turned out the lights in Alaa's room, she asked him if there had been a power outage – apparently she can now see the difference between dark and light. In a few weeks, a month or two at most, she'll be able to go home again.

Sending the children back to Iraq when their care is complete is hard, Pogue and Miller say. "You go to all this trouble to restore this little girl's eyesight and then we're sending her back where for all we know she'll be blown up in a week," Pogue says.

"I worry about Asra'a," Miller says. "I wonder how she's doing, if she's OK. It changes the way you hear the news." It's a change that Pogue and Miller hope will be contagious. "The human ties are very important," Miller says. "I don't think anyone who gets to know one of these children and their families is going to accept the idea of war in the same way again. It brings it home to you how savage war is."

In a few weeks, 7-year-old Abdul Hakim, will fly to Pittsburgh for medical care. Hakim will need a prosthetic eye and reconstructive surgery on his jaw, which was shattered last year by fire from a U.S. air strike in Fallujah. Nearly four years after the project to help Asra'a began, four children will get the medical care they need. It's a lot, and it's also nothing. Hundreds, maybe thousands, of other children need similar care and may never get it.

"It takes so little time to do the harm, and so much time to undo it," says Miller. "It's like throwing sand into the ocean at times. But you can't let the hugeness of the problem paralyze you. There is a lot that we as individuals can do. When I'm frustrated, I remind myself of an old Jewish proverb – 'Save one person and you save the world.'" ![]()

For more information, see the Web site at www.nomorevictims.org.

Alan Pogue's photographs are available at the Web site for the Texas Center for Documentary Photography, www.documentaryphotographs.com.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.