The Short Unhappy Life of Sophia King

One bloody morning in June concludes a tragic journey

By Lucius Lomax, Fri., Aug. 2, 2002

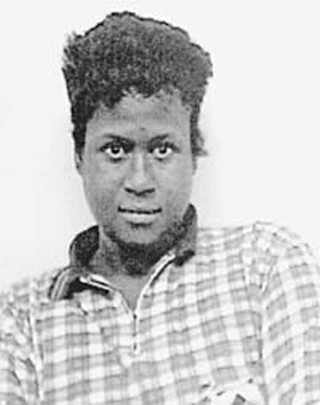

The short unhappy life of Sophia Chante King came to a sudden end a little after 8:45 on the morning of June 11, when a police officer's bullet entered her left armpit, punctured her left lung, and tore through the upper right chamber of her heart. She died where she fell, on the grass behind her apartment at the Rosewood Courts housing project, where she was known and feared by residents and employees alike. Mother of two, frequent flyer in both the criminal justice and mental health systems, predator and prey, she was just 23 years old.

In death, Sophia King has attracted more attention than she did in life. Her shooting has caused the public, and public officials, to review both police use of force and the community's response to the mentally ill. Her shooting has led to complaints of police brutality ("They shot her in the back of the head") and police bias ("They wouldn't do that to a white lady on the west side") and has shown, once again, how inept the Austin Police Dept. can be in addressing public perceptions of how cops do their jobs. Her shooting has provoked, at least implicitly, threats that this might be a long, hot summer in East Austin. Her shooting has split the city's traditional liberal alliance about how much grief to express over the death of a woman who, the police say, was a public menace. Her shooting has also meant, last but not least, that Jim L. Humphrey can now lead his life in peace.

When the autopsy was performed on Sophia King the afternoon of her death, the medical examiner noted that the decedent was "clothed in white ankle high socks and cut away turquoise pajamas." She wore "a pair of cut away black underwear and [a] pair of black and white flip-flops." Her nail polish was chipped metallic blue. "There is a tattoo," the coroner wrote, "over the right thigh depicting, in cursive writing, the words 'Jim L. Humphrey,' and below this a heart." Sophia King's police file -- the portion made public -- is 118 pages long, not including her last fatal encounter with officers. There's no real order to what the police recorded, just snapshots of Sophia during the past five years -- public intoxication arrests; her dubious eyewitness testimony of a gang-related gun battle ("After talking with King it was very obvious that she is biased against the Bloods and is close friends with the Crips"); the times her young son and daughter were struck by cars, both accidents apparently the result of Sophia's negligence. But to the degree there was any persistent theme in her adult life, it was her pursuit of Jim L. Humphrey, her love interest, 17 years her senior, alleged father of her second child (also named Jim Humphrey), his denial of paternity, and his desperate attempts to escape her affections.

'Love Makes You Do Crazy Things'

The police first became witnesses to the progress of the romance in November 1997, when Humphrey reported that someone had put sugar in his car's gas tank. Apparently there had been two prior criminal mischief complaints in which Humphrey was the victim, though it's not clear that his young ex-lover was the perpetrator. This time, however, he had few doubts. (It should be noted that the sugar-in-the-gas-tank episode was before Humphrey's tires were slashed, which Sophia apparently admitted to. The actual stalking of Humphrey and his girlfriend likewise had not yet begun.) "Humphrey stated that the gas cap to the vehicle was missing," an officer recorded. "Humphrey stated that he suspects his ex-girlfriend King, Sophia B/F 17 YOA [that is, "black female 17 years of age"] ... Humphrey stated that everything has started happening since they broke up."

Bracketing this romantic interlude, Sophia also had several police interactions unrelated to Jim L. Humphrey. The police didn't really seem to take much interest, filling out reports as if by rote. In 1995, for example, when she was only 15, and before meeting the love of her life, Jim L. Humphrey, Sophia made her first appearance as a victim on the police blotter. She had stayed home from school to accompany a family member to an attorney's office. (The stages in Sophia's social development were marked not by school dances or family functions, but by court dates and hospital visits.) According to the police report, Sophia's aunt, who lived with her and was angry to find she hadn't gone to school, "grabbed King to drag her away. King resisted. [The aunt] struck King in the face and left visible welts on King's face ... several long scratches on the right cheek." The officer concluded, "This case, as reported, appears to be a situation of parental discipline rather than assault."

Four years later, Sophia was the victim again, in a dispute with a neighbor: "During the argument, Cedric pulled out a knife and cut Sophia on her left leg in the knee area, causing a two-inch laceration about a half an inch in height. EMS Medic 4 stated that the cut was severe and needed stitches, but Sophia denied treatment." King was given a case number for her complaint and told to get in touch with detectives: "Case suspended until victim makes contact." She never did make contact with detectives, but she made plenty with practically every other blue suit in "Charlie Sector" (the Central East Command, east of I-35 and roughly between 51st Street and the Colorado River). Beginning in 2000, Sophia no longer turns up in police reports as a victim; she had taken on a new role, as violent perpetrator.

When her son was struck by a neighbor's older child, Sophia, in time-honored parental fashion, told her 3-year-old boy to hit back. Little Jim obeyed -- and was promptly hit again, by the neighbor's 6-year-old. Sophia struck the 6-year-old in the back with her fist, the blow making a noise that a witness said he heard across the housing project yard. Busted. A few weeks in county jail for assault.

Within the next year, she reached what appeared to be bottom. In November 2001, upon release from the Austin State Hospital after a diagnosis of schizophrenia, she went to her mother's house to reclaim her children, who had been placed in their grandmother's custody by Child Protective Services. The incident report dryly recounts the outcome. Sophia's mother, Brenda Elendu, tried to stop her from taking the kids: "Ms. King then pushed Ms. Elendu with both hands across her chest. Ms. King then hit Ms. Elendu with her hand across Ms. Elendu's left side of her face causing her pain. Ms. King then pushed Ms. Elendu up against her vehicle and applied her forearm to Ms. Elendu's neck causing her pain. Ms. King then grabbed Ms. Elendu's neck and began to choke her causing her pain. Ms. Elendu then stated that as she tried to get away ... ." Sophia's 5-year-old daughter was witness to the assault on her grandmother. Busted again. Back to jail.

Considering what was to come, Sophia's relationship with Jim L. Humphrey must have seemed like the best years of her life. Humphrey told police that he sometimes slept with her not because he cared for her any longer, but to keep her from showing up at his new love's home. According to the police reports, even when she complained that he abused her, she still professed affection: "King stated that the two were arguing because King went to Humphrey's new girlfriend's residence ... to ask Humphrey to buy their newborn some pampers ... Humphrey does not deny being intimate with King, but stated that he is currently scheduled to take a paternity test to find out whether the child belongs to him. ... Humphrey stated that King has threatened to kill him in the past and made this statement to him, 'Love makes you do crazy things.'

"At times King was smiling and laughing as I interviewed her in reference to the assault so I questioned its validity. King did make the comment before I left to speak with Humphrey, 'If he comes here again hitting on me, can't I kill him in self defense?' This was also said with a chuckle. Humphrey nor King had any prior involvement for assault. Humphrey also stated to me that King has been following and harassing him in a manner that suggests she is a 'fatal attraction.'"

On another occasion, Humphrey complained again to police of an assault by Sophia, who he said slapped and scratched him, demanded child support, and "rambled" through his van, taking from the van one dollar bill. Following that report, dated September 12, 1998, Jim L. Humphrey disappears from Sophia's officially documented life.

The Safety Net

To understand how Sophia Chante King ended up on a coroner's examination table, it's helpful to know about an obscure dispute between the city of Austin and Travis County. To understand that dispute, you have to know the direction that mental health care in this country has been taking for the last two decades. The catch-phrase is "community-based care." The idea first appeared in the Sixties and gradually took hold over the following decades: the goal being to get the mentally ill out of institutions and back into houses and neighborhoods, the "least restrictive setting," where they could swim, albeit slowly or erratically, into the mainstream.

The difficulty was that when they stopped swimming and began to thrash around -- because, for example, they had stopped taking prescribed medications -- there needed to be someone who could subdue or restrain them, as necessary, or just talk to them, or even drive them to the State Hospital. The average police officer did not have the necessary sensitivity training. In a surprisingly enlightened move, Travis Co. created a unit of "mental health deputies" in the sheriff's department. These deputies became the sensitive side of local law enforcement: Dressed in plain clothes, with the option to carry a weapon or not, they talked to people; in hostage situations, they were used as negotiators.

"We were forced to become mental health care providers," says Michael Sorenson, one of the sheriff's senior mental health deputies. The only drawback, Deputy Sorenson says, was that there were too few of them: no more than eight or nine in all, usually only one on duty at any time, for the entire county, including the city. As the city and county grew, to more than 800,000 people in 2000, there were still only eight officers and a supervisor.

In 1999, the county entered one of its periodic budget crunches and was also being pressured to increase the number of mental health deputies to cover the increasing population. The city was already contributing $93,500 to the sheriff's mental health unit budget, but the county asked for more. That was all the prompting the Austin Police Dept. needed. The police chief took the $93,500 and decided to start his own mental health unit. "Chief [Stan] Knee decided he wanted to do his own thing," said a sheriff's spokesman. (The police administration declined to comment, but through a spokesman, Assistant Chief Rick Coy said that he will be glad to discuss details of this reorganization after any King-related litigation has been concluded -- which, given present courthouse dockets, should be in about five years.)

Chief Knee's own thing was to set up a three-tiered system of coverage in the city, with the majority of his 1,250 officers having the basic six hours of mental health instruction mandated by the state, 100 officers getting 40 hours of training, and four or five state-certified mental health officers in a special city police mental health unit, modeled after the sheriff's.

After Chief Knee's decision, there was some bad blood between the Sheriff's Office and the APD. The sheriff's people thought they had been doing a good job, but because they were covering the whole county with so few people, their response times were long. Yet the city police were, and are, inexperienced: Without exception, mental health specialists interviewed for this story say that if there is an emergency, and they have to call someone, they want the sheriff's people -- not the police mental health unit -- to respond. They felt that way, they say, even before Sophia King was shot. Last year, after receipt of a federal grant and under prompting from officials including Probate Judge Guy Herman, who hears most of the involuntary mental commitment cases in Travis Co., the police mental health unit and the sheriff's deputies were brought together to work out of the same location on East Avenue. The co-habitation was forced on the police as a step toward increasing coordination between the two departments, and also to let the city's officers learn from the sheriff's experience: The idea, said one official familiar with this arranged marriage, was that "APD, which is new at the game, would learn what S.O. [Sheriff's Office] knows, which is old at the game."

In considering Sophia King's death, the important thing to remember is the structure of the police mental health response: the average officer with six hours of training, dozens of officers with 40 hours, and a small, officially designated mental health unit of four or five officers, certified by the state.

A Noisy Neighbor

In November 1999, just after the city and county's dispute over funding, Sophia King had problems of her own: A fire broke out in her home at the Booker T. Washington housing projects. The cause was a stove burner left on and unattended -- Sophia and her kids were uninjured, but the apartment was gutted, with $15,000 in damages. (Sophia denied that she had left the stove on.) "I met with Ms. King and told her that she was to meet with ... the manager of Rosewood Courts at 5:15 that afternoon," a Housing Authority official wrote in a report on the fire, "because that is where we had an available unit to relocate her to. Ms. King was reluctant, but I explained she had no choice in the matter."

Sophia's time at Rosewood might be called her blue period. There was apparently little joy in her stay there -- for her or for those around her. Her neighbors noticed that she looked much older than her twentysomething years. Occasionally, perhaps defensively, she put on airs. "I am a high school graduate," she told them, as if she had a Ph.D. from Oxford. (She was a graduate of Anderson High, class of '98). What bothered people most was that Sophia was often mean. A Hispanic woman, who arrived at Rosewood after Sophia, said that the first words Sophia King spoke to her, as a greeting, were, "Fuck you, bitch." The Hispanic lady adds, "I didn't even know her" -- although they did share intimate space for a few hours one day this June: Sophia died at the lady's back door.

People outside Rosewood Courts might blame life in public housing for Sophia King's unhappiness. The problem was not where Sophia lived, but how she lived. By the spring after her arrival, Sophia had established her reputation at Rosewood. She was loud, she threw trash out her back door, she liked to spit -- she was accused once of going to the manager's office after a dispute and spitting on the doorknob. In an April 2000 Housing Authority note, the then Rosewood manager wrote, "Had to speak to Sophia about her stereo being turned all the way up. Asked to see if she got my note from yesterday asking her to return the house key she borrowed. She was abrasive and combative." A few days later, she was still late with the rent, and she was also presented with charges for damage to her apartment at Booker T. Washington. An undated note adds: "The police were here and no one would come to the door. Her children were not at the unit at this time. APD told her to come out of the unit. She said it was none of their business, APD told her that she either came out of the unit or she would be arrested. She came out." By August, management was considering eviction.

Calling 9/11

Sophia King was swimming against the stream. Opened in 1938 and now one of the oldest housing projects in the country, Rosewood Courts has been through some tough times, but under the Housing Authority's recent management, there has been new paint, new plumbing, and landscaping -- Sophia had a split-level, two-bedroom, one-bath home that was going to be just as nice as she kept it. Certainly the area is tough: There were two murders and seven rapes at Rosewood Courts in 2000 alone, but nasty crime stats are partly a result of location. The 123-unit complex sits at the intersection of Rosewood and Chicon, an intersection with heavy foot traffic. A lot of people passing through the projects don't necessarily live there. Many of those passersby, it seemed, stopped to see Sophia. Neighbors report a variety of men going through her doors, especially after the kids were taken away, the unproven accusation being that she was selling drugs.

The critical moments in Sophia's life continued to involve the arrival of a blue-and-white police cruiser. In late August of last year, Sophia and her 5-year-old, Kearra, were riding bicycles back to Rosewood from Blackshear Elementary School, when Sophia apparently got ahead of the child. As they approached home, a van belonging to the Housing Authority was turning into a driveway at the projects. Sophia passed by safely, but the van struck Kearra. "King was very upset and cursing," the investigating officer reported. "She had a moderate odor of an alcoholic beverage on her breath. King made several statements that she was 'going to get paid' in regards to the incident." Kearra and bicycle were dragged by the van, but the little girl was not badly hurt. No ticket was issued, and no money was paid, a Housing Authority spokesman says, but Rosewood residents report that the accident was especially upsetting to Sophia because she continued, every day, to see the Rosewood Courts employees who had been involved.

The beginning of the end for Sophia King followed soon afterward. Like the rest of us, only apparently a little more so, Sophia may have suffered from post-9/11 hysteria. On the morning of October 18, not long after the anthrax attacks on the East Coast, police were summoned by the new Rosewood manager, Diana Powell. Sophia King had apparently lost whatever anchoring in reality she had left.

The first officer on the scene was Francisco Rodriguez, who interviewed the manager: "She stated that King was outside in the cold half-naked and that she was throwing all of her furniture and clothing out of the apartment. ... Powell pointed me towards the direction of King's apartment where I could see her furniture and clothing scattered all over the front yard. King had left all windows and doors open to the apartment and a radio on full blast blaring from within." Officer Rodriguez was soon joined by Corporal George Jackoskie. (In his report, Rodriguez described Jackoskie as a mental health officer, but an APD spokesman says Jackoskie is not in the mental health unit now.) The officers searched the apartment, which was empty and, according to Rodriguez, "a total mess." He called for a police photographer to come to take photos. Neighbors reported that Sophia had been "acting really weird" for two days, although when she first pulled her mattress out on the lawn they thought she was preparing for delivery of a new bedroom set.

The police eventually found Sophia on the grounds. She was covered with kitchen cleanser: "King started to tell us that she knew that the staff at the Rosewood projects were trying to kill her," Officer Rodriguez wrote. "She was saying that she was cleaning her apartment and in doing so she noticed dust in her bedroom. She stated that she and her children started to get ill and she just knew that the dust was anthrax. ... She stated that she did not want to go back to the apartment ... that the staff was trying to kill her and her children."

"Sophia told me," Jackoskie reported, "that the neighbors treat her and her children bad to keep them inside their apartment to gain more exposure to the 'bio,' in her apartment. Sophia thinks that the management of the Housing Authority are after her because one of her children was hit by a Housing Authority van in August and she is suing them and she thinks they are doing this to her." She told the officers that she had put Ajax cleanser and bleach on herself to get rid of the anthrax. In response to the standard psychological questions, she told Jackoskie that she wasn't hearing voices and she didn't want to hurt herself or anyone else. He disagreed. "It appeared to me that Sophia posed a danger to herself and others." Child Protective Services was called to take temporary custody of her children. Jackoskie drove Sophia to see an emergency-care psychiatrist, and then left her with nurses at the State Hospital. She was at the State Hospital "for a period of time," according to one person there who is familiar with her file. When she was released, she went after her mother, who had been given custody of the kids.

'They Couldn't Do Anything'

It's at that point that the law enforcement/criminal justice system first failed Sophia King, according to the source at the State Hospital. "Sophia's problem was that she would get off her medication," this individual says. (A conclusion borne out by the toxicology report of Sophia's autopsy: At death she had no alcohol or recreational drugs in her blood, but she also didn't have traces of any of her prescribed antipsychotic medications.) It's a common cycle: People leave the State Hospital after being stabilized, suddenly they're feeling better, and think they don't have to take meds any more. They end up back at the State Hospital, or in jail.

After assaulting her mother, Sophia went to jail. An official at the State Hospital suggests that instead of putting her in a cell for two months -- which the judge did -- a better alternative would have been to put her on probation for a year with the condition that she take her medication. That's usually the procedure. Yet jail was a pretty good second choice -- it's sad to say, but the Travis Co. Jail is the biggest mental health provider in the county, bigger even than the State Hospital, and the guards there are reportedly not bad in servicing people with special needs.

Sophia King was shot and killed on the second Tuesday in June. The preceding Sunday and Monday were like the days preceding her commitment in October: loud music, things thrown from the apartment, dysfunctional behavior, police visits. The police were called at about 3am on Monday, but according to the complainant, a next-door neighbor, "The cops said they couldn't do anything." The APD is not releasing those reports, but some of the Housing Authority's documentation is available.

On the Friday preceding her death there were more notations from Rosewood's management: "Santiago was out here and said hello to Sophia and she started cussing him out ... Santiago feels that she is a danger to our children with the way she is acting." On Monday, the day before she died, there were three management entries: "Received a call from Benina stating she was playing her music very loud all weekend long, Vicky called the answering service stating the music is very loud and trash everywhere and that police could not get in there." "I called the police to check into the unit because of complaints and that the loud music is still going on and the trash is everywhere because of her tearing up items." "Police came out to check on her stating that she was okay and turned down the music finally after the police pounded on the front door." The last two entries were signed by Diana Powell, the Rosewood Courts manager, the woman Sophia would allegedly attempt to kill the next day.

The police said she was "okay"? It must be a matter of perspective.

Even today, a month later, if you take a walk around Rosewood there are clues to be found at the scene, imprecise and sometimes contradictory -- like the police reports that she was "okay." If you ask the people you meet, it seems no one in the neighborhood has a name. But everyone has an opinion.

Circles Within Circles

There are what can be described as concentric circles of knowledge around Rosewood Courts. If you start about a block away, you meet someone like the young black man eating barbecue at the bus stop: "Brothers [are] mad," he says. The police officer who fired the shot was "wrong for busting her like that. She dropped the knife." It's a widely held (although not unanimous) opinion that Sophia King was unarmed at the time she was shot. "The knife" was thrown from the front door, when she was tossing her kitchenware, which somehow implies that she couldn't still have one in the house, or among the things she'd thrown out the back door. The corollary to this theory is that a white policeman saw an unarmed dysfunctional black woman, Sophia King, chasing Diana Powell, a white woman -- and "shot the nigger." The young man at the bus stop says that everyone knows who "the law was that did it" -- i.e., the officer who pulled the trigger -- and that "brothers talking about meeting up this weekend about it," in other words, to get revenge. That hasn't happened yet.

Get a little closer to ground zero, some of the outlying apartments on Rosewood Courts for example, and nobody knows anything. Even a month after the event, people don't want to get involved. Get a little closer still, approaching the homes of Sophia's immediate neighbors, and people have opinions once again, and even some facts. They knew Sophia King, and lived with her, and no one can be silent about that experience.

A woman whose front door opens about 25 feet from Sophia's says she saw Sophia King with a knife tucked into the back of her waist on Monday, June 10, the night before the shooting. "She was looking for trouble with anybody she thought was tough," this neighbor says, although she believes Sophia was mostly bluff. "I just ignored her." That night, police officers came on Sophia-related calls at least once, according to this neighbor. As usual, when the police arrived, Sophia closed and locked her screen door and wouldn't come out. At one point the neighbor says she heard Sophia express to an officer, through the screen door, what psychiatrists call "suicidal ideation," that she wanted to die, etc. (On a previous visit she had allegedly asked a cop, "Why you keeping us here on death row?") This raises the suspicion of an occasional syndrome among psychiatric patients: "suicide by cop." The lady who saw Sophia with a knife subscribes, in part, to this theory: "Sophia wanted to die, and the police wanted to get rid of her." There's also the possibility of simple attempted homicide: The assistant manager of Rosewood claims that Sophia had threatened to kill her on Monday.

On Tuesday morning, Sophia was more agitated. She had thrown her housewares -- plates, utensils, and at least one knife -- out her front door. "We had a bad feeling coming to work that morning," says B.J. Gonzalez, Rosewood Courts assistant manager. Gonzalez said that staff was preparing to start a routine administrative meeting when they got word that King was on the warpath. Diana Powell and co-workers went to take pictures as eviction evidence. Powell had already recommended eviction, but administrators had not yet made a final decision. The police were called to the scene.

At this point, although people keep moving, time stops.

Sophia's screen door was closed with her behind it; she was inside her home. At least one unidentified cop (not the one who would fire the fatal shot) was standing a few feet away, talking to her, talking to the neighbors at the front of the house. People in nearby apartments had left for work or were asleep; according to Gonzalez, Rosewood Courts doesn't really wake up until 11am. There was a mess on the ground outside Sophia's door. While one officer stood at the front door, another arrived at the back of her apartment. "That's how cops do it," explained a neighbor who has witnessed a few busts, "one to the front door, one to the back."

At that moment, Diana Powell started to slide through a hole in the fence beside Sophia's building, to get to the back yard and take pictures of any mess Sophia had made there as well. Neighbors say that Sophia saw Diana turn to go through the fence. Perhaps Sophia did see her -- or sensed that the people who wanted to kill her were on the move. "She just flashed on Diana," says the assistant manager. In any case, Sophia King started back through her house, out her back door, where she would have her brief final meeting with Diana Powell and Senior Police Officer John Coffey.

Officer John Coffey

John Coffey's record is pretty impressive. He graduated with a criminal justice degree from the State University of New York in 1983, and by the time he became a police cadet he had already been licensed for five years to carry a pistol, knew how to use a police baton, and was certified in police defensive tactics. During college he came to the Austin Police Dept. on an internship ("I was scheduled to work in five areas," he gushed on his original APD job application form, "when I finished I had worked in eight areas.") Before coming to Austin permanently, he was a farmhand in upstate New York and a security guard at a drug store, catching shoplifters and doing bad check collection.

Officer Coffey's civil service file is like Sophia King's arrest record: It provides only snapshots, in this case of a long and creditable career. (There could also be omissions. The public file includes letters of commendation but not letters of reprimand; the only disciplinary actions that the department reveals are those that involve suspensions, firings, or demotions, none of which applied to officer Coffey.)

Still, there are a few noteworthy moments in Coffey's time with APD. There is John Coffey, for example, on bicycle patrol on the Drag, arriving on the heels of a bank robber and scooping up money that the bandit has dropped on the street. He got a commendation for collecting the loot. There is more praise for help on a big drug bust, and for participating in a raid on a burglar's home.

His evaluations were generally good. He kept in shape and at least twice won honors for being in the top 10% for fitness in the department. (When he was hired, 16 years ago, his weight was given as 165 pounds and his height as 5 feet, 6 inches; at the time of her various arrests, Sophia King was listed as anywhere from 5-foot-6 to 6 feet, and her weight was always around 200 pounds. Sophia also outweighed Diana Powell by at least 50 pounds. She was, as the coroner described her, "a big girl.")

Through the years, officer Coffey's supervisors were happy to report that he did many cop things right: He kept his gun side protected during interactions with the public, he didn't hog the radio, and didn't use profanity. There's the now-famous '98-'99 performance evaluation, the last one made public by the department, in which he received a failing grade in judgment, 4 out of a possible 10: He was unable to identify "legitimate alternatives that can be used as responses in addressing problems." (In other words, he couldn't improvise in a crisis.) Yet he also received a 9 out of 10 on his understanding of the use of force -- indeed, he was a cadet trainer at the time, teaching defensive tactics. His paperwork was never great. "John has the potential to become an outstanding officer," his supervisor wrote in 1999, "but events in his personal life have become a distraction and affected his judgment." Also in 1999, he received a letter of commendation for helping to set up a display of knives and for, apparently, explaining to the public how quickly someone with a gun can react to a knife-wielding assailant. Across the front of the letter is scribbled, "Thanks for the hard work!" signed "Chief Knee."

Sophia, What's Going On?

Just before Sophia King's death was reviewed by the grand jury, a prosecutor remarked privately, "It looks like a clean shoot." Coffey had a good reputation, and the rules of engagement were clear. But the police also had a witness they weren't making public. A teenager standing at her upstairs window in Rosewood Courts had claimed to see the shooting.

The section of Rosewood where Sophia King lived is arranged in a rectangle, with a grassy back yard in the center. The teenager's window looks out over most of the yard. In a brief interview with a reporter (permitted by her mother), this 17-year-old confirmed the police version of events, at least in part. That morning, she heard the commotion, looked out her open window, and saw Coffey, Powell, and Sophia King. Sophia was standing over Diana Powell, the girl says, and had a knife in her right hand. The teenager says she plainly heard Officer Coffey tell King, "Put down the weapon." She has no doubt of Sophia's intentions: "She was on top of her with the knife." The teenager realized that something bad was going to happen -- and she turned her head away. "One or two seconds later," she heard a single shot. "I turned away and ran downstairs," she says. She adds that she was taken to police headquarters and signed a sworn statement, but she was not invited to testify before the grand jury.

Both this girl and her mother had had difficulties with Sophia, so an argument can be made for bias. But nearly everybody in the neighborhood had also had problems with this walking train wreck of a woman. The girl's version of events has some support in the evidence. Deputy Medical Examiner Elizabeth Peacock says that the bullet traveled a straight trajectory downward through King's body, meaning that King was headed toward the ground when she was shot. "People don't stand still when you're trying to shoot them," Dr. Peacock says, and she has no idea what Sophia was doing at the time she was hit, only that the trajectory of the shot was downward. A possible conclusion is that in the "one or two seconds" after the witness turned away, Sophia had started her attack.

Diana Powell's testimony, admittedly secondhand, is in line with this possibility. A Housing Authority spokesman says that Powell is on leave "under a doctor's care," but B.J. Gonzalez, the assistant manager, says she and her boss have discussed the incident and "Diana is completely freaked out. She keeps seeing it happen again in her mind." Gonzalez says that Powell's version of events is that by the time Officer Coffey fired, Sophia was on top of her, pinning her to the ground, had stabbed once and missed, and had her hand raised to stab again. Gonzales says that another staff member was also witness to the shooting.

The police have accused the press and public of distorting events that day, but apparently there's been some distortion on all sides. A member of APD recently said that Officer Coffey had no excuse but to fire because he was "25 feet away from a 300-pound woman with a butcher knife." The weapon, according to the medical examiner's investigator, was just a "common kitchen knife." And the teenage witness says that when she saw him, Coffey was about 6 feet away from King, which undermines police assertions that he could not pick his shot or perhaps even use his baton.

Police are trained to fire in those circumstances, certainly, but they are not required to do so. Choosing a less lethal resolution means thinking outside of the box. "They could have shot the woman in the foot or the hand," says Harry Wilson, former host of Austin public affairs TV program The Lion Speaks, who has been highly critical of the police in the past. "These motherfuckers are the forces of oppression. These motherfuckers are trained to kill. My 'take' on the subject is fuck the police. When it's a nigger, they always kill."

According to residents, Sophia King ended up on her back, her hands raised at her sides, "as if she was laughing." She lay there for three hours, while a small, half-unfriendly, half-curious crowd lingered, murmuring that even in death Sophia was being disrespected. The police publicly blamed the medical examiner for the delay in removing the body, but the medical examiner's log shows that the coroner was not even called until an hour and a half after Sophia had been declared dead by EMS. Chief Knee was out of town at the time of the shooting, but when he returned he was said to be displeased that a crowd had been allowed to gather at the scene -- his fear, apparently, possible public unrest.

Actually, there's already been considerable public unrest. A lot of people are not pleased with what went down, and they may have good reason. Apparently the officers who saw Sophia King on Monday, the day before she was shot, never referred her case to the police mental health unit. "I wish that intervention on Monday had been made known to the MHU," said an official familiar with the case. This official says that one of the officers who saw King on Monday was a policeman with 40 hours' mental health training but who did not inform specialists, even though department general orders require a mental health officer to be dispatched as soon as possible to such a situation. "Maybe they wouldn't have done anything," the official said of the mental health unit. "But maybe they would have gone over there and said, 'Sophia, what's going on?' Tuesday morning, Sophia's problem was she was sick, and needed emergency care."

In addition to APD, the county's judges also do not look good. A plan had been proposed, before the King incident, that one county court-at-law and one district court would begin last October hearing all mental health-related cases, so that those two judges and the prosecutors assigned to their courts would become particularly experienced in the field -- learning about the resources available, effective strategies, etc., instead of leaving this very specialized field to the whole Travis Co. bench. District Court Judge Julie Kocurek had agreed to take the position adjudicating felonies, but her fellow criminal district judges refused, citing the bureaucratic hurdles of transferring mental health cases to her court and taking over parts of her docket.

How long the jail's relatively good reputation in mental health cases will last is also uncertain. Larry Hauser and Jefferson Nelson, the two psychiatrists who have managed the jail's psychiatric unit for the last 17 years, just ended their contract in a dispute over budget cuts. Dr. Hauser, who also manages psychiatric services at Brackenridge Hospital, says psychiatrists are reporting similar budget cuts in Harris County, in San Antonio, Dallas, El Paso -- the whole country. Citing the Andrea Yates case in Houston and the Columbine massacre in Colorado, he says that the cuts that government is making now "are going to end up costing society more in the future."

God, Lawyers, and Guns

"How do you justify taking a person's soul?" asks one of Sophia's aunts, Alice Pickens, who is serving as a family spokesperson. (She was not the aunt involved in the 1995 incident with Sophia.) "Justice will prevail." She declines to discuss Housing Authority complaints that the family did not intervene with Sophia when asked. She says that the family is putting its faith in God -- but she's also suing the city. "It was a wrong deal. It never should have happened but it happened, but we are going to make it [through this]." In response to all questions about the shooting itself, Sophia's mother says, "Ask Diana Powell." Ms. Elendu says there's a cover-up on the part of the media and the police, "but I know what happened, and the man upstairs knows what happened." She said to tell Officer Coffey that as a Christian, she forgives him -- but she's still going through with her lawsuit.

In fact, no one comes out looking good -- if anyone can be said to look good after a killing. The sheriff's people had warned that APD wasn't ready to fly on its own. That appears to be true. Austin-Travis County Mental Health Mental Retardation had helped push the sheriff and police mental health units into cohabitation. That was necessary. But B.J. Gonzalez says that the morning of Sophia's last outburst, a short while before she was shot, Gonzalez called MHMR, who said they couldn't do anything, and referred her to the sheriff's mental health unit, who told her they were tied up and couldn't come out. "I called everybody," she says. The sheriff's people told her to telephone the ordinary police emergency line, which she did.

Deputy Sorenson of the sheriff's unit says he knows few details about the King case. In defense of the police, however, he says that on occasion force is necessary: "When you're dealing with a person who's psychotic, hearing voices, whatever, sometimes talking to them isn't enough." Yet, that Tuesday, had Sorenson been dispatched to see Sophia, the outcome almost certainly would have been different. He's been doing his job for 18 years, and, he remarks casually, "I don't even carry a gun." ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.