Common Ground on the Colorado

The newest park on the river takes shape

By Dan Oko, Fri., April 26, 2002

"Common ground creates community," says Ted Siff of the Austin Parks Foundation, who has been helping marshal the latest efforts to develop the Roy G. Guerrero Colorado River Park, 363 verdant acres of Austin parkland just east of Longhorn Dam. Siff is being neither coy nor metaphorical, He's simply offering a truism on the importance of metropolitan parks in this day and age, when suburban-type sprawl threatens to devour the last open spaces in many Texas cities. People turn to parklands for romantic walks, for ballgames and birthday parties; to take a break from the busy-ness of urban living, jobs, traffic, and taxes; to learn about the natural world, the plants and animals that share our habitats; and, of course, to exercise.

Listening to Siff, you can quickly be persuaded that projects like the Colorado River Park -- the final piece of the Town Lake park system, named in honor of the retired deputy director of Parks and Recreation affectionately known as "Mr. G" -- can do a lot to make up for not just our alienation from the land, but our alienation from each other as well. "This goes beyond 'We want a pretty neighborhood,'" Siff says. "This has to do with the city's social and health goals. If you have 400 kids playing Little League or bird-watching, and some others out picnicking with their families or just enjoying nature, you don't need a truant officer. You can chalk it up to 'midnight basketball' if you like, but if you supply these sorts of outlets and activities, you won't need to build youth detention centers. Basically, it boils down to 'Pay me now or pay me later.'"

Even with an area eventually larger than Austin's beloved Zilker Park (355 acres), it would have been hard to imagine a couple of years ago that the 363-acre Colorado River Park could become so many different things to so many people. Funded through a 1998 bond election that ultimately will supply $10 million for development and construction of ballfields, recreation trails, and natural areas along the river, in the fall of 1999 the park was the subject of a series of highly contentious public meetings. Viewed as the ideal spot for an Eastside destination that one day might rival Zilker with its soccer fields, hike-and-bike paths, miniature train and so forth, planners set to work to address the city's vision of what the Colorado River Park might look like 20 years from now. But as they did so, kayakers demanded a paddling course, local Little League coaches complained that the neighborhood was still owed ballfields, bicycle advocates argued for expanding the Town Lake hike-and-bike trail, and environmentalists and a host of NIMBY-minded neighbors urged the foundation and Austin Parks and Recreation officials to leave the riverfront alone. Even today, Karin Ascot of the local Sierra Club chapter maintains, "If you're looking at the amount of space being used and the amount of time it's available, these natural areas hold a higher value."

Balancing Needs and Resources

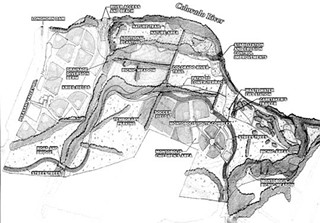

Within the next week or two, the local landscape architecture firm Richardson-Verdoorn, which designed the city of Georgetown's open space plan as well as community parks in Cedar Park and Dripping Springs, takes over the reins from the San Francisco-based Hargreaves and Associates. A look at the master plan generated by Hargreaves, and approved by the City Council under former Mayor Kirk Watson, shows a remarkable effort to take into account almost all potential users. Along the upper stretch of the park, farthest from the river, there's a patchwork of ball fields and areas dedicated to organized sports (Ascot, a soccer player, perks up a bit when she hears that a handful of soccer fields are in the mix). Away from the neighborhoods and the developed play spaces, the plan calls for paths, picnic areas, and zones for passive recreation, such as tossing a Frisbee, birding, or simply walking among the wildflowers.

This spring, the city unveiled a new one-mile extension of the Town Lake loop, paid for with federal transit money, and stretching from the Longhorn Dam to the new Montopolis Little League complex. PARD has set its sights on restoring the natural grasses of the Blackland Prairie that historically grew on the property, and also plans to correct some of the drainage problems that turn areas of the park into a boggy mess whenever flooding occurs. This will also prevent portions of parkland from being swept into the Colorado River, which resumes its natural flow after it passes through the Longhorn Dam. "What the master plan has achieved," Siff says, "is an optimal balance of what citizens wanted based on the resources available."

PARD boss Stuart Strong points to the city's efforts to restore native grasses and improve drainage as representative of his agency's commitment not just to providing a recreational resource, but also to PARD's conservation goals. "The park will provide an interesting assortment of human uses and biological communities," says Strong. "We think we can really jumpstart the nature area. We're designing this so we will be able to minimize the most expensive maintenance costs and concentrate on the areas that need the most attention."

Strong goes on to describe the efforts of the city Wastewater and Water Protection division to find ways to channel water that currently bisects and trisects the park when heavy rains come. An old farmer's gully forces water to drain directly through the middle of the park right now, he notes, but new channels will be cut through the property to minimize the impact of flooding. Moreover, Strong is well aware that by allowing the park to retain much of its natural character, the city not only provides a model of Austin's native ecology for visitors, but PARD can save money on maintenance required by ball fields and other high-activity zones elsewhere. "The visitor will see a great nature area, but we know this will also make it a much easier site to maintain," he says.

Maintenance issues remain on the back burner, though, as the city is still just cranking up the first phase of design and construction, including not just landscape restoration but the extension of park roads and the expansion of parking areas, as well as additional nature trails. Nonetheless, even with this work pending, a variety of stakeholders, ranging from the Travis County Audubon Society to the Montopolis Little League, express their appreciation for the work done thus far, and view the park as offering tremendous potential for both neighborhood groups and for the whole Austin community. Many compare the plan to New York City's famed Central Park, a magnet for city folk wanting to run their toes through the grass. City Council Member Raul Alvarez could be speaking for any one of these interests when he says, "We're happy it's finally moving along. It's providing recreational opportunities for the neighbors, and we've been able to balance those with the fact that we don't have that many natural wildlife areas left within city limits."

Building Community Support

Park organizers make clear that the bottom line must be balanced with the demands that will eventually be placed on the resource. The first phase of park development, which will likely take the next two years, calls for $2.5 million in bond money. But the overall cost of developing the park over the next decade or more has been estimated as high as $40 million -- in other words, bake sales just won't cut it. Ted Siff is well aware of that fact, and he's already begun to turn the foundation's attention to firming up the sort of private-public partnerships that most analysts think will be necessary for shoring up public land in Texas during the 21st century. Potential funding sources range from naming rights for ballfields to out-and-out donations from the same individuals and foundations that currently back APF, which has an annual budget of $300,000. "I'll always advocate for more park funding," Siff says. "But whether we're in a time of fiscal restraint or in a boom time, there will always be a need for citizen involvement in the parks as well."

Siff goes on to talk about the three "Ts" -- time, talent, and treasures -- which the community can bring to the not-so-proverbial common ground. As proof, he points to the fact that last year, volunteer hours helped account for more than $5 million worth of in-kind contributions to Austin parks. Already, a pair of springtime clean-ups at the Colorado River Park, assisted by volunteers and members of the local AmeriCorps chapter, a sort of domestic Peace Corps, resulted in the removal of tons of garbage from the site. Mattresses, old appliances, discarded carpet, shopping carts, and burned-out water heaters were hauled away, and while litter remains, especially along the river bank and even suspended in some of the trees, the effort resulted in making the park a much more hospitable place for an early morning jog or late afternoon meander. "We would still like to see an increase in city park maintenance and the development budget," says Siff, "but our job right now is to help turn up partnerships and funding opportunities to help Parks and Recreation do their job." ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.