The Road to Rail

Can the A-Train Work and Play Well With Smart Growth?

By Mike Clark-Madison, Fri., July 21, 2000

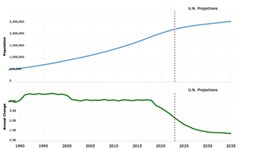

Wanna do something about the horrible traffic on the highways? Light rail ain't it. Wanna do something about our ever-dirtier air? Nope, light rail ain't that either. Wanna change the way Austin looks and works for decades to come? Now let's talk about light rail. Lest any rail fans think this is aid and comfort to the enemy, this is all equally true of State Highway 130 or any other road-warrior dream. The problems of today are not going to be solved, or even very much minimized, by multibillion-dollar infrastructure investments taking decades to complete. Like fruit trees, you plant these systems for your grandchildren.

And the gift you're giving the grandkids is not free-flowing traffic and country-fresh air. Even if light rail succeeds in Austin beyond anyone's expectations, beyond any other city's experience, it will still carry only a small increment of the trips that get made in a bona fide big city. (As would SH 130, whose improvement on the status quo will be barely noticed by anyone outside of southeastern Williamson County.) Even the most transit-friendly cities are still crowded and soiled. Metro areas of 2.5 million souls, which Austin will be by the time these projects are finished, have traffic congestion and less-than-clean air. They just do, and people deal, and they can still be great cities.

But our choice of transportation system will, more than anything else, determine where and how those 2.5 million people breathe, eat, and sleep. A road like SH 130, even if it spawns the status-quo crop of tilt-wall strip-crap that's choking the highways we already have, will at least direct growth into our Desired Development Zone, currently undesired because it has lousy infrastructure. But rail, proponents say, lets us focus that growth on different kinds of development: you know, mixed-use New Urban compact city-transit-oriented neo-traditional Smart Growth stuff.

And furthermore, the fans argue, rail lets us put those projects into marginal, decaying, and fast-obsolescing chunks of the urban core, improving our tax base and putting money in all our pockets. In recent years, light rail has, across the country, seduced not only urban-planning mandarins but the real estate industry, which should help the A-Train's chances of seducing y'all come the November do-or-die ballot. Even rich conservative Republicans dig it!

But in Austin, we tend to vote not on what we know and think, but on what we feel and want. Do we want Austin to be a city with the sense to invest in transit? Or do we want to be a city with the sense to not get on the train? We will build that city, whichever it is, over the next few decades. And once we do, it'll be very difficult to change our minds.

Dallas Sees the Light

Road warriors scoff at the notion that light rail will transform land use all by itself. As well they should. It takes work and commitment on the part of cities, transit agencies, the private sector, and the citizens themselves to turn an investment in transit into the genuine stuff of Smart Growth. And it doesn't always translate into immediate returns on the transit investment. But sometimes it does, and on a scale grand enough to offset light rail sticker shock.

Witness our friends to the north in Big D, home to the only up-and-running light rail system in the middle third of the country. Though Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) pays its propers to mobility and air quality, and proudly touts how its system has exceeded ridership expectations (which, truth be told, were pretty conservative), the agency can't wait to tell you about the development that's happening all up and down its line, and even in places like Plano and Garland where the train has not yet arrived, and the good fortune thus created.

To list all the projects around all the DART stations that -- according to the agency, its member cities, or the developers themselves -- are transit-dependent, returns on the light rail investment, would be tedious. But they stretch throughout the macrocosm of the Metroplex. Most of the current DART system lies in the poor side of town, south of the Trinity River, where public and private investment has long been lean. But the train is credited with reinvigorating Lancaster Road in South Oak Cliff, which now has grocery stores and banks (long rare there as in East Austin), and with attracting affordable housing and customers for small businesses in the area.

There's also the Downtown Dallas boom, featuring three major skyscraper renovations (the huge Adam's Mark hotel moved into the old Southland building because it was on the rail line), major employers relocating downtown, and a lengthening strand of loft buildings. The surrounding burbs are hoping to catch a bit of this wave; urban-village town centers are planned for both Plano and Garland, and the "Telecom Corridor" through Richardson is now being graced by Galatyn Park, a 500-acre multiple-use development with the DART station at its very center. Mind you, none of those lines actually exist yet.

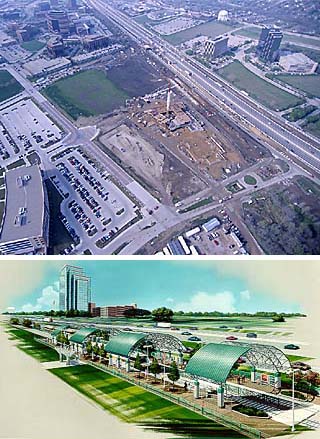

But the big stars along the line, the projects that explain why North Texas developers -- not known as a class for romance or altruism -- have gone gaga for DART, are hip mixed-use urban things in the close-to-downtown neighborhoods. Cityplace, the underground station where DART will link to the old McKinney Avenue Trolley, and thus to the Smart Growth pioneer projects of uptown Dallas, will itself be surrounded (and surmounted) by a 43-story office tower, hundreds of apartments, and retail, including the inevitable arthouse theatre.

Another of those will be up the line in the massive Mockingbird Station complex, which comprises not only 200,000-plus square feet of retail (partly in a converted parking garage) but 200 lofts in the old Southwestern Bell warehouse. On the other side of the station is the old Dr Pepper building, itself being converted into 450 lofts. And continuing the adaptive-reuse theme, on the other side of downtown, the Cedars station lies opposite Southside at Lamar, the lofts-and-more conversion of the old Sears Roebuck distribution complex. The Dallas Police Department is building its new headquarters next door.

Ron Coughlin of Matthews Southwest, developer of Southside at Lamar, says the project has so far begun or built out about 2 million square feet, representing an investment of about $300 million, which is about a third of what DART spent on the entire existing system. "And that was in an area that hadn't seen 10% of that development in years, for miles and miles to the south," Coughlin says.

"We picked out the site looking at several factors -- the proximity to the CBD, the market for loft apartments, and the Convention Center [one rail stop away across I-30] -- but the DART station was most important," Coughlin continues. "Having a DART station changes a building into an area, with the station at its heart. It creates a location where there may not have been one. Very few things create something like that." A widely touted University of North Texas study found that property values and rents along the rail line were 25% higher than at comparable properties elsewhere in Dallas, though anti-rail road warriors (such as the Texas Public Policy Foundation) have raised some valid concerns about this analysis.

But the facts still seem plain enough. However, given these times of plenty, wouldn't this investment along the line -- now worth about $800 million total, at DART's last count -- have been made anyway in a hot market? Well, yes, developers and (more importantly) their lenders would have found some other way to spend their money. But DART fans hold that the train carried that money to where it was really needed, to urban core districts hollowed out by bust, blight, and flight, instead of to far-off Metroplex villages that had not yet been graced with their very own tilt-wall power centers.

"That investment was going to happen," says our own Council Member (and real estate pro) Will Wynn, "but without rail it would have been scattered from Duncanville to Denton. Because of rail, the private sector voluntarily jumped at the chance to be on the line. That's the strongest argument for light rail -- it's an agent of land-use change."

Did Dallas really want land-use change, or did it just want the money? "What DART did is accelerate the area's maturing into what it probably would have become anyway," says Coughlin. "It didn't used to have access, within a half-block, to restaurants and to the CBD and so on. So that moved us along. And it affects parking requirements, which helps you negotiate with municipalities, and it was a big, big deal for the Dallas Police. Would we have built it without DART? Yeah, but the size and scope would not have been the same. It would have moved a lot slower, and we would have started and stopped and seen how the market reacted to us."

No Two Cities Are Alike

Most light rail cities have not been lucky like Dallas, where the economy boiled over just as the train started to roll. But other light rail cities are, after all, different cities, with different expectations and values and goals for light rail to meet -- which is something to remember when road warriors, as they often do, talk about rail's "disappointing" results elsewhere. Rail may be controversial everywhere, but it's hard to find a city where something approaching a mainstream consensus is "disappointed" with its rail line.

In St. Louis, the Metrolink moves large volumes of human biomass to and from the big destinations -- stadiums and arenas, the Gateway Arch and riverfront casinos, the universities, the airport -- and isn't as much expected to do anything else. In Sacramento, the RT Metro was an explicit alternative to widening the highways and mostly runs in the same highways' rights-of-way. And in San Diego, the Trolley travels vast distances to connect downtown to its far suburbs and to Mexico; it's the only realistic travel option for crossing the border, without a car, from south to north, which thousands of Mexican nationals do daily.

Despite these other goals, those other cities have sought transit-oriented redevelopment; they are not run by fools. And Big D has benefited from their pioneering. When Portland debuted its MAX system in 1986, it granted 10-year tax abatements to developers locating in its designated transit corridors, because in 1986 -- hell, even in 1996 -- few in the real estate industry (or, fair to say, in the transit industry) had a clue about light rail and land use. In Portland, where the quest for compact urban form is both a legal imperative and a civic religion, that was considered, by at least a bare majority of the locals, money well spent. In Dallas, that would never happen, but the past five years have sexified Smart Growth, and Big D had no need for such devices.

So could it happen here? Of course, as long as Austin is even hotter than Dallas and, from the national perspective, still a fairly untapped market. "What we really have to do is make hay while the sun shines," says Wynn. "Bad stuff is being built all over town right now, so an [economic] slowdown might be good to stop it. But now is when we have capital, and cachet, and a consensus that we're heading into the United States of Generica and would rather go somewhere else. Right now, the people who build these things want to be here badly."

But Austin probably doesn't want a land rush on the Dallas scale, and neighborhoods might be comforted to know that Capital Metro, at least, does not officially expect it. In the economic impact analysis Cap Met produced for its federal-funds application, the agency projected $885 million in development value over the entire 54-mile system, in 2012 dollars (the first year of "steady-state" ridership). Given the pneumatic property values in our city -- which are now, on average, higher than those in Dallas -- this may prove to be wildly lowball. But it's not such a great return on a $2.2 billion investment, though Cap Met says rail's total economic impact -- including savings from cheaper and faster travel -- will outpace the project's capital costs.

Mostly what Austin is lacking, compared to Dallas, is opportunity -- for example, a few hundred million square feet of built space waiting to be redeveloped, reoccupied, reused, and reincorporated into the neighborhoods. Even if the hipsters on Lower Greenville Avenue objected to the manifest density and unabashed yuppiedom of nearby Mockingbird Station -- which, it being Dallas, they probably didn't -- a 50-acre chunk of obsolete and unlovely commercial real estate is not much better as a neighborhood landmark.

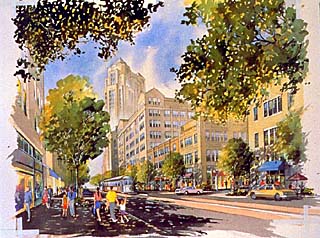

In Austin, developers, the city, Capital Metro, and whomever else will have to be more choosy, since the in-town populace is seeking just enough Smart Growth as is needed to fill in the few dark and empty spaces while leaving their neighborhoods unchanged. "In our analyses, we've assumed increased development and density in some areas but not in others," says Cap Met general manager Karen Rae. "Do we think density will happen downtown? Of course -- it already has. Or on the north end of the line near McNeil, or at Mueller and the Triangle, or out toward the airport." (See maps for a close-up look at four potential hot spots, p.26)

"But we don't see that every place on the line is going to have short- or long-term redevelopment potential," continues Rae, "and that's because of the neighborhoods. We may see modest changes but not major ones, because we're trying to improve neighborhoods and their integrity, not destroy them. Wholesale redevelopment at every station doesn't make sense. But redevelopment doesn't have to be a 20-story building. Eastside neighbors say they want to have a day care facility at a station. That's development. Taking into account what the neighborhoods want to leave for their grandchildren is a key part of this process."

Neighborhoods as Players

OK, humor us a little: Let's assume that rail can give trackside neighborhoods the opportunity to get exactly the scale and density of new development they desire. Let's further assume that, through means ultimately separate from land use, this development can be calibrated to be affordable and accessible, to walk the fine line between revitalization and gentrification. And let's assume that these projects will not simply be a new flavor of generica, in which identical tilt-wall Home Depots are replaced by identical loft-and-Starbucks combos. How do we make this happen?

Well, being Austin, we start by planning. Capital Metro's current phase of light rail planning -- the preliminary engineering/environmental impact study (PE/EIS) required by federal law -- will refine and resolve the final alignment and station locations, and thus set the table for any redevelopment feast. "Developers have asked us how they begin (to build transit-oriented development)," says Karen Rae, "and my answer is that they need to be involved in the alignment process. Developers here are very interested, all over the region; they want to be in on the ground floor because they know it'll be a positive. We need to get that interest into the process, where it can be balanced with neighborhood and stakeholder interests."

The neighborhoods likewise want the PE/EIS process to be part of the solution and not the problem. "We're going to need to settle on where the priorities for redevelopment will be on this or future lines, and which areas we instead need to focus on preserving and carefully managing, given the influence rail might have," says Austin Neighborhoods Council president Will Bozeman. "I think we're finally ready to take steps to work together -- which really hasn't happened to date -- where Capital Metro, the city, and the community have been seriously planning land uses, where the community visions and goals are, and where rail can feed into that." The ANC plans, Bozeman says, to "prompt Capital Metro to work with the city's planning and development functions to make sure its plans are indeed community-based ... to a greater degree than we've ever seen in this city."

For its part, the city has two fronts on which to fight its Smart Growth planning battles. One is in the ongoing series of neighborhood plans. Each of the six already-approved neighborhood plans, and each of the plans currently in progress or close to it, includes a potential chunk of the A-Train route. "Win, lose, or draw, we need Capital Metro to integrate with neighborhood planning very seriously," says Bozeman. "And we need to be very clear about what areas -- whether they be station areas or adjacent to the alignment -- are going to have [zoning] overlays, and what developments are allowed, and how a firewall can go up to prevent speculative influences that impact property values -- both positively and negatively -- and how those impacts can be addressed."

The other city planning front is its long-running and tortured attempts to define citywide transit corridors -- for either rail or bus service -- where increased density can be promoted. After trial transit-corridor balloons were floated and then promptly shot down by neighborhood interests, the city has hired a consultant and convened a task force to guide its second attempt. "It's both process and criteria that they'd be working on," says Mayor Pro Tem Jackie Goodman, including "how [corridor plans] would overlap with neighborhood plans [or] mandate a special planning process involving more than one neighborhood."

For each corridor, "ultimately, you're deciding what this road will be when it grows up," Goodman continues. "Every corridor is a product of a line of different neighborhoods with different character that may call for a different mode of transit or development. If you don't want to plan for the corridor to be what it is now, you have to do something different that's right for that corridor. That's what we're dealing with now, and all of that should have happened a couple of years ago, in my humble opinion. But since we haven't done it, and we're doing things like a 24-hour downtown, we really need to get on this."

Goodman is also pushing for the city to hire "instantaneously" a new "crack team of transportation planners ... and we'd have to pay them the bucks they could get in the private sector, because we really need some expertise. We can't use the lowest bid here." Said team would help resolve the issues that will come up, over and over, in both neighborhood and corridor planning, with increasing rapidity, as land uses start to change and more people start crowding into less space.

So much for planning for a land-use future that would make the light rail investment worth making. Do we then tie developers to the tracks, through regulation, or glue them there with incentives, to fulfill these plans promise? Maturing light rail cities have gotten land-use and redevelopment impact through some, or a lot, of public sweetening. Portland, San Diego, San Jose, and (soon to be on line) Minneapolis all have active and innovative redevelopment authorities that actually intervene in the market, along with some generous incentives, and Portland, being Portland, also has rules that forbid the wrong kind of development along the MAX. The same cities, along with St. Louis and Denver, have likewise tied their big-deal stadium, convention center, and urban-marketplace deals to their rail investment.

In Austin, the only comparable public-private initiative is Mueller redevelopment, and rail is (out of political necessity) only loosely connected to the airport project, even though its planners view transit as absolutely essential to Mueller's success. But Dallas -- which, though different from Austin in ways we all hold dear, is likewise subject to Texas antipathy to taxpayer subsidy and land-use regulation -- has managed to avoid needing a public lever to do the heavy lifting of urban redevelopment, and if Austin gets rail off the ground this year, we can avoid the same.

But even if we need neither carrots nor sticks to drive developers to the rail line, we still will need some sort of active process to manage trackside growth and redevelopment. Dallas did not sit and watch its land rush happen; the city, and now its neighboring cities (DART serves 15 communities in the Metroplex), got in front of the train with station area land-use plans, and DART itself involved developers with its own station projects from day one.

Karen Rae foresees a similar role for Capital Metro if and when it builds an A-Train. "I would expect that we, pending a successful referendum, would create such an arm that would work hand-in-hand with the economic development folks at the city," she says. "I can see a combined organization of Capital Metro, the city, Travis and Williamson County, to help the private sector get ready."

Why should we bother with such active oversight, if the private sector is wetting itself with excitement over rail-spawned opportunities? Well, one reason is to make sure we don't get projects that, while Smart Grown in an abstract sense, are appalling to Austin sensibilities. (Think Gotham.) In terms of character and ambience, "many in Austin would not really want the kind of development Dallas has on its rail line," says Wynn. "We would need to customize. Our real estate products are already different from what's built in Dallas, but we as the public sector need to help developers do what we think we want."

Redevelopment authorities in cities like San Diego can make sure that developers give the community exactly what it wants, as a condition of the deal. We all saw how well that's worked here, with the CSC deal among others, so if we're going to open the door to such projects all across town, we probably need better systems than we have now. We are not ready to create such systems, because we've never had to before. "Other cities with such economic development experience had it because they needed it, and then they got good at it," says Wynn. "Austin, for better or worse, hasn't needed it, and now we'd be skipping an entire step of the process."

And, if we want to create systems that will promote, ensure, or enforce the ideal use of our rail investment, then we need to decide what that ideal really is. "I think as a community we're doing a lot of things that are prescriptive, that we know are sustainable, and that we see from other places are the right way to go," says Will Bozeman, referring to the hydra-headed Smart Growth Initiative(s). "But we aren't yet at the horizon where we know how station-area planning and redevelopment might meet those goals, for the neighborhoods or for the marketplace. We'll hopefully be drawing those conclusions soon and then have a better idea of what systems or incentives, if any, are needed."

Really, folks, if we've been talking about light rail for 15 years, we should have decided these things yesterday. As it stands, it would be mighty nice if, as a diversion from the ongoing pre-referendum light rail debate -- which is already tired, superficial, and forensic, and it's only July -- we addressed the land-use question head on, before we decided what kind of transportation system our grandkids will inherit.

"The reason, I think, that so many of our big projects slogged through the mud for years is that you don't have everybody's attention," says Jackie Goodman. "If you don't get people involved to let them know what's happening, and what the choices are, they won't know how to react. They'll be reacting out of emotion. Once you give them the mechanism to be involved, or to get the information, then it's not that big a deal. They may moan and groan, but they'll live with it." ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.