What's on Tap?

By Dan Oko, Fri., June 16, 2000

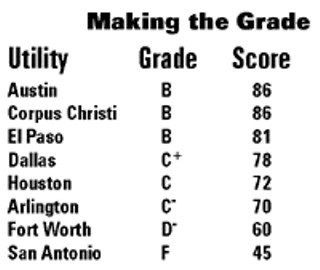

It may be difficult to forecast what the future holds for the Colorado River, but a recent report card on Austin released by Texas Clean Water Action indicates that the city's water system is one of the safest among major metropolitan water supply systems in the state. CWA program director Sparky Anderson explains that the grading system measures not only municipal drinking water safety but also the extent to which utilities provide consumers with information detailing the source and quality of their drinking water, as required by 1996 amendments to the federal Safe Drinking Water Act.

Austin tied with Corpus Christi for the top spot with a high B, ahead of six other cities, all of which rely on rivers for their drinking water. Surprisingly, El Paso received a B, despite the fact that the Rio Grande is viewed as one of the most degraded streams in the Southwest. Dallas, which relies on the upper Trinity River, received a C+, while Houston, which had to shift its water supply in recent years from underground wells to Lake Houston, a part of the San Jacinto River, got a flat C. San Antonio's low F came largely because the utility failed to provide consumers with adequate information about their drinking water.

And managers and monitors across the state indicate that, even apart from the quality of our municipal drinking water system, Austinites have even more to be thankful for. John Jadrosich, public affairs officer for the Trinity River Authority -- an LCRA counterpart that oversees water supplied to nearly half the state -- says he anticipates that 50 years down the road, both greater Houston and the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex will be much more reliant on water shipped from East Texas. But before that point, Jadrosich notes, the TRA must negotiate the rocky shoals of 1997's Senate Bill 1, a water supply measure following the drought of '96, to make sure all its customers get what they need.

"Water's one of those things worth fighting for," says Jadrosich, "but we hope we can get through this process without starting a war between Dallas-Fort Worth and Houston." One of the problems faced by the Houston area, he says, is that the historic use of wells has begun to drain the aquifer beneath the city. As the natural, underground storage tanks fail, things have gotten so bad that subsidence -- or the collapse of land areas in the low-lying city -- has become a serious issue for some residents. Just as Houston has turned to the San Jacinto reservoir that bears the city's name, nearby cities such as Livingston have also come to rely on surface water, including the Livingston Reservoir, part of the Trinity River that captures water processed by Dallas' multibillion-dollar treatment facilities.

Ironically, while Dallas doesn't have the same sort of industrial infrastructure as the upper Gulf Coast, a recent petroleum spill in nearby Lake Tawakoni in the Sabine Watershed has contributed to water woes in the region. The Tawakoni spill, which dumped the toxic gasoline additive MTBE into the Sabine drinking water reservoir, is a graphic example of what Austin opponents of the Longhorn Pipeline want to avoid, but Jadrosich views the spill as an anomaly, and maintains that while the future presents some problems for TRA, there's plenty of water to go around; like most aquatic administrators, his agency is busy trying to deal with the issue of non-point source pollution.

The Rio Grande faces a host of issues more extreme than those seen in much of Texas. First of all, the river not only gets diverted to El Paso and other Texas communities, but also supplies northern Mexico with water for a variety of uses. Add in the assortment of industrial plants on both sides of the border spilling waste into the river, and the issues of depletion and pollution go hand in hand. In El Paso proper, says Gilbert Ayala, an environmental protection specialist with the Texas Clean Rivers program, issues of salinity and persistent bacteria are causes for concern. The current goal, Ayala says, is to figure out how, exactly, effluent and diversions impact the Rio Grande -- many critics already contend that people downstream have fallen ill from contaminated water -- and only after the effects have been measured, he says, can administrators turn their attention to the issue of long-term supply. Meanwhile, Ayala is quick to point out that water treatment facilities in El Paso appear to be taking care of these problems for city residents. "The Rio Grande looks like a nice river until you get to the Texas-Mexico border," says Ayala. "After that there just isn't that much water. To understand it, you really have to see it for yourself."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.