No Man's Land

Substandard Conditions Are a Way of Life for Northridge Acres

By Cheryl Smith, Fri., June 9, 2000

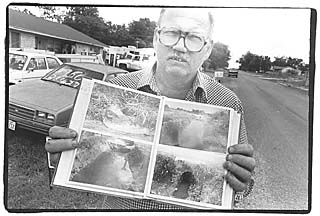

Turning off FM 1325 onto tattered Northridge Acres Drive is like rolling into the Twilight Zone. The foul scent of sewage permeating Kenneth Snyder's house and the green stagnant water in the drainage ditch parallel to his yard are dramatically out of sync with the choice real estate surrounding the displaced subdivision he calls home. A sign for a 328-acre commercial multi-use development, La Frontera, coming to the former farmland less than a block from his home, and the new apartments on the other side of the chainlink fence a couple of blocks from his corner -- home to many of the techies of nearby Dell Computer Corp. and other high-dollar companies -- exemplify the growing gap between Northridge Acres and its neighbors. These disparities, exacerbated by the fact that Northridge Acres is currently drawing its water from a nearby fire hydrant, set the scene for a strained relationship between the subdivision and area government officials. The subdivision's 300-plus residents cope in different ways. Kenneth Snyder, a bicycle repairman who vends soft drinks out of a Coke machine next to his front door, opts for making daily phone calls to the offices of elected officials in Austin, Round Rock, Travis County, Williamson County, the Texas Legislature and several state agencies.

"What burns me is we're so close to everything but we gotta live like this," says the 50-year-old Snyder, who along with his wife, Laura, has lived in Northridge Acres since 1985. "It's like I told Gov. Bush's [office], 'You're down there worrying about Mexico and stuff, and here we are with a colonia in your back yard.'"

Standing in his front yard, Snyder squints, then attempts to straighten the crooked, wide-framed glasses high on his nose. "Nobody wants to hear about colonias here in Travis and Williamson counties, but they've got 'em," says Snyder, who is fond of likening his community to the more than 1,400 substandard communities on the Texas-Mexico border.

Developed in 1961, the Northridge Acres subdivision straddles the Travis and Williamson County lines, about a half-mile west of I-35, off FM 1325, also known as Burnet Road. Back then, Austin boasted a population of 186,545, and its city limits stopped several miles south of the rural community. The city of Round Rock's population was less than 2,000, and its city limit stood five miles to the southwest. In the early days, Northridge Acres' only neighbors were cows, a drag-racing track -- silenced years ago -- and a 100-year-old house where the Texas Chainsaw Massacre was filmed. The old house is now a restaurant on Lake LBJ.

Early on, the subdivision was a draw for those wanting to escape the hubbub of city life. "I didn't like the idea of living in the city. It [Northridge Acres] was a more quiet, serene environment," says Fidel Acevedo, who bought his grassy, one-acre lot in the back end of the subdivision in 1971. "Most everybody owned at least one acre of land. All the neighbors knew everybody. You always knew whose kids were out in the streets."

Time and rapid growth have changed those days for good. Austin's city limits now stop only two miles short of Northridge Acres, while Round Rock, itself a burgeoning community, literally bumps up against the subdivision and has a population of almost 53,500. Neither city, nor their respective counties, has ever officially supplied the subdivision with sewer or water services. The city of Austin, whose extra territorial jurisdiction (ETJ) includes Northridge Acres, recently finished extending a sewer line in the community's direction for the southernmost portion of portion of La Frontera, which also falls within the city's jurisdiction. With retail stores, restaurants, a multiscreen theatre, a hotel, an apartment complex, and office buildings, the new mixed-use community will reimburse Austin for the multimillion dollar sewer line extension in the form of tax-generated revenue. It wouldn't have been cost efficient to provide the line solely for Northridge Acres, says Mike Erdmann, wholesale services manager for Austin's water and wastewater utility.

Widespread Phenomenon

All things considered, Northridge Acres isn't as bad off as many of the border's more downtrodden colonias. Nobody uses an outhouse, the roads are paved, and water flows directly into homes. But, Northridge Acres' 640-foot-deep well -- its only permanent water source -- went dry last summer, the downhill end of the subdivision is plagued by drainage problems, and many residents' septic tanks leak into their yards and overflow easily, making flushing during a rainstorm a potential health hazard.

"When I heard about [Northridge Acres], it was clear to me that it was a colonia. The colonias are much more widespread than has been understood," says Peter Ward, a professor in the University of Texas' Sociology Department and LBJ School of Public Affairs. Ward is also the author of Colonias and Public Policy in Texas and Mexico: Urbanization by Stealth. As in Northridge Acres' case, Texas' colonias generally fall into what Ward calls "an administrative no man's land," meaning they are outside the nearest city's limits or in its ETJ. Most of Texas' unincorporated areas go largely unregulated. Counties don't have the authority to require developers to provide running water under state law. They can only force developers to state whether or not water will be made available to a subdivision. And until last year's legislative session, developers who said they didn't intend to pave roads in unincorporated neighborhoods didn't even have to file building plans with counties.

Texas' constitution is extremely pro-landowner because of the state's open-frontier, pioneer roots. As Paul Sudd of the Texas Association of Counties puts it, "Texas has this image, for better or worse, as a haven for property rights." By contrast, the constitutions of several other states, such as California, make no distinction between city and county land use authority. Explains DeAnn Baker, of the California State Association of Counties, via e-mail: "We both share police powers and zoning authority equally -- our authority is mutually exclusive."

In Mexico, Professor Ward notes, the powers of cities and municipalities -- the Mexican equivalent of counties, are lumped together, leaving less room for "jurisdictional ambiguity." In his book on colonias, Ward writes, "There is an urgent need to give greater consideration to the way in which we, in Texas, approach the colonias phenomenon, and to think more aggressively and imaginatively about how we can intervene more effectively."

Border Improvements

In the late Eighties and early Nineties, images of border residents -- the majority of them U.S. citizens -- living in shacks and cottages without electricity or plumbing caught the national media's attention. The publicity forced local, state and federal officials to address a situation that had been tolerated for decades. As a result, Texas has spent hundreds of millions of dollars over the past decade trying to bring the border's colonias up to par with development standards first established in the 1989 Legislature.

Lawmakers tightened the standards, known as the Model Subdivision Rules, in 1995, requiring water and sewer hookups, electrical connections and subdivision blueprints for border communities. Developers are now prohibited form selling residential lots without water and sewer hookups, roads and drainage.

Vick Hines, a legislative aide for Sen. Carlos Truan, D-Corpus Christi, says the proliferation of communities lacking decent water, sewers, and, in many cases, paved roads, hasn't been addressed sufficiently statewide. "I think it's really important to get the big picture on this stuff," says Hines, who has worked for Truan on colonia regulation legislation for more than 10 years. "Until rural counties near major metropolitan areas wake up, they aren't going to get anything solved."

The state as a whole is a breeding ground for colonias because in addition to its weak county government, it has several large metropolitan areas where people can move to the outskirts. Searching for a better quality of life and fleeing high municipal land taxes, low-income individuals are migrating from inner-city neighborhoods to low-cost subdivisions on the fringes of town.

"What we have are not substandard subdivisions, but substandard housing. Living conditions here [in colonias] are not any worse than when you put several individuals in a two-bedroom house in the middle of the city," argues Scot Campbell, a Harlingen-based developer who has been building subdivisions, some of which are considered colonias, in the Lower Rio Grande Valley for 22 years.

According to 1990 U.S. census data, Texas has the eighth-highest poverty rate in the country, with an 18% rate compared to 13% nationally. Disturbing as this statistic is alone, it is much more alarming when coupled with data from the Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs' (TDHCA) year 2000 report on low-income housing. According to the report, there is a shortage of affordable housing for low- and moderate-income Texans because the majority of professional developers have been building for more lucrative markets. Central Texas is especially susceptible to substandard development the report says, because it is one of the state's fastest growing regions and because Travis, Hays, and Brazos counties are three of only six state counties in which low-income individuals spend 45% or more of their income on housing.

According to Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission (TNRCC) statistics, the number of septic tanks installed yearly in Texas, a figure that roughly corresponds with the number of homes being built in areas without sewage systems, is on the rise. The number of applications for on-site sewer system permits filed during 1999 -- 48,940 -- rose from 43,129 in 1997. The statewide application process is based on the honor system, so the septic tank figures are likely lower than the actual amount, notes Annette Maddern, program administrator for TNRCC's on-site sewage facilities program.

An obstacle keeping substandard communities in most non-border counties from making improvements is the difficulty in receiving funding. Counties adjacent to the border or with a per capita income 25% lower than the state average qualify for the state's Economically Distressed Areas Plan, which was created in 1989 to curb colonia development. Qualifying counties that enforce the model subdivision rules receive state and federal aid for projects. But with a per capita income of $27,610 in Travis County and one of just over $23,450 in Williamson, local substandard communities like Northridge Acres have very limited funding options for potential improvements.

Northridge Acres was awarded a grant of about $300,000 from TDHCA to install a sewer system in 1997. But, progress has been slow to none, partly because residents are divided over whether their Small Towns Environment Program (STEP) grant, which requires them to supply a portion of the project's labor and construction resources, is even appropriate for their community, which has a significant elderly population.

Also, some Northridge Acres residents are bitter about the fact that neither Round Rock nor Austin wants them, and openly vocalize their discontent, weakening their community's relationship with cardholders simultaneously. "It's been rocky all the way through," says TNRCC utility specialist Carol Limaye, when asked about the so-far-unsuccessful sewer project.

"It's been stall, stall, stall, all the way through. Nobody wants to do anything," says Snyder, who airs his gripes weekly on public access television. "They figure if they give us enough hell that we'll just give up, leave and they'll take over the land," he says of Austin officials in this case. "They want to put all the fancy houses in and everything."

Because Northridge Acres is in Austin's ETJ, the city has the authority to annex the subdivision at any time. In fact, Austin has taken the westernmost portion of Northridge Acres into its city limits before. The city annexed several strips of land in its ETJ in 1985 as part of an effort to control area growth, says Erdmann, of the city's water and wastewater utility. Northridge Acres, along with some other tracts of land, was de-annexed in 1989. State law began requiring municipalities to provide extensions of water and sewer services to annexed areas in 1987, but city officials say that since the requirement wasn't retroactive, the new law had nothing to do with the de-annexation.

Austin dumped Northridge Acres because, one, the state legislature was clamping down on the city for doing large strip annexations, and two, because residents, unhappy about paying city taxes without receiving water and sewer services, petitioned to be removed from the city's limits, says Diane Quarles, Austin's former principal planner, now with the city of Santa Fe, New Mexico. The city, however, doesn't have a Northridge Acres de-annexation petition on file. "They fought bitterly to be removed," she says. "It's a case of, 'be careful what you wish for.'"

Residents of Northridge Acres then clamored for the entire subdivision to be taken into Austin's city limits in 1997, the year the city did a mass annexation, Quarles says. "It was just rearing its ugly head again. The city didn't do anything wrong," she adds.

Northridge Acres residents, who say they paid city taxes from '85 until '89 beg to differ. Snyder says the annexation stretched as east as the telephone pole at the edge of his one-acre lot. He paid about $1,500 annually during those four years, he says. Because Northridge Acres is in Travis County and partially in Williamson County, it is difficult to trace where Snyder's tax dollars were going. Travis County Appraisal District's computer records indicate that his property has been in Williamson County since 1990. His address was consequently deleted from Travis' computerized tax records. Williamson County doesn't have any record of Snyder's taxes during the Austin annexation years.

"They just dropped us and didn't do nothing for us," says Snyder, who's been told his signature appears on the community's elusive de-annexation petition, but he contends he doesn't remember signing it. None of the former Austin taxpayers got their money back because cities aren't required to return tax money to residents of de-annexed areas. "There is no process or method for returning taxes after you've collected them. There wasn't any way to send the money back to the folks," says Erdmann, adding that the Northridge Acres tract was not the only community the city de-annexed in 1989.

A Tangled Web of Water

Until another water source comes along, Northridge Acres' residents will continue getting their water from a fire hydrant in Round Rock's Corridor Industrial Park. Almost all of the subdivision's houses are tied into the hydrant, located near the green dumpsters and semi-trucks of Michael Angelo's, a frozen Italian food company, which occupies a space in the industrial/warehouse facility. The community's well was sealed last summer after it went dry. Some residents say that when it had water, it was contaminated because of the leaking septic tanks.

The well's water pump was black and slimy when it was removed to fill the hole up with cement, Snyder says. However, water quality tests conducted by members of the Northridge Acres Water Supply Corporation, as well as the Texas Department of Health, have never found evidence of fecal contamination.

As it happens, Round Rock's water and sewer lines are closer to Northridge Acres than Austin's lines. Despite this, Austin -- which pays Round Rock more than $1,000 a month for the fire hydrant water, then bills Northridge Acres the same amount -- had to tunnel under FM 1325 to extend its water lines in the subdivision's direction.

"They're in Austin's ETJ. That's how the law is set up," says Jim Nuse, Round Rock's director of public works. "Their [Northridge Acres'] sewer and water needs to come from Austin."

The 16-inch extension, which has been in place since February and cost about $14,000, is still dry because Northridge Acres' Water Supply Corp. is responsible for connecting the new line to the subdivision about 200 feet away, says the city of Austin's Erdmann. "We're all buttoned up and ready to go," he says. "They just need to tie in."

It's not that easy, argues Nettie Brown, vice president of the Northridge Acres Water Supply Corp, and a longtime resident of the community. The water supply corporation hasn't been able to take care of its connection facilities because the Texas Department of Transportation, which owns the land on either side of FM 1325 -- where the potential sites for the hookup are located -- won't grant the subdivision approval to use their property, she says.

The highway department will approve use of its land for almost any public utility if the community wanting to install the lines hires a professional engineer to draw up plans, and if the professional builder pays the installation cost up front to ensure the job gets completed, Erdmann says. The water supply corporation is paying an engineer to install a hookup, but he hasn't done anything yet, Brown says. "I just think they want to stop the growth in this subdivision," she says.

Mark Petrusek, TxDOT's utility coordinator for the Austin area, says Northridge Acres can install its water line on TxDOT land. It's just a matter of the subdivision and the city of Austin deciding who's going to pay for the hookup, and then applying for the permit. "It's just a matter of them deciding what's going to be done," he says. "[The water supply corporation] just can't seem to afford it. They want the city of Austin to do it for them."

Another obstacle for the corporation has been finding the funds to pay for the estimated $20,000 connection fee, Brown says. That amount was reduced to $15,000 about a month ago, when Travis County agreed to cover 25% of the cost on the condition that the corporation submit to a financial audit, says Erdmann, who represented Austin at the Commissioners Court meeting where the decision was made. Travis County will ask Williamson County to match the contribution, he adds.

Round Rock had intended to disconnect Northridge Acres from the hydrant June 1, a more than fair deadline since the water arrangement was temporary and Austin's line extension is complete, Round Rock's Nuse says. Now, Round Rock is extending the water cutoff deadline on a day-to-day basis. "Our goal is not to put people out of water. Our goal is to have the water supply corporation act responsibly," he says.

Life at Northridge

With a long, manicured front lawn hosting two tropical looking Spanish Dagger trees, a brick-red picket fence, his own private well in the back yard and a four-bedroom fieldstone exterior home, Fidel Acevedo, who spent 28 years working in a handful of departments at IBM, is one of the community's more upscale residents. He pulls a white lace curtain in his den away from a set of French doors leading to a narrow sunroom facing his back yard. He points to a cluster of new multi-story houses on the horizon of his property line. Then he stares and frowns at the rusty trailer surrounded by a pile of clutter in his next door neighbor's back yard. "[Northridge Acres] has the problems of any colonia that you'll find, but then again, there's a lack of responsibility on the part of the homeowners," says Acevedo, the Democratic chairman of Precinct 225, which includes Northridge Acres, part of the Wells Branch community -- a little of Round Rock and a little of Pflugerville.

In a white V-neck T-shirt, dark Wrangler jeans and open-toed leather sandals, he doesn't look to be politically connected. But his incessantly ringing cordless phone and atypical sympathy toward local politicians gives him away. "We cannot live that way. I think [residents] need to realize that they cannot have this trailer-trash mentality. They can't just expect the county to keep giving them everything," he says.

Meanwhile, the La Frontera development is sprouting up. Its eight-story Marriott is currently under construction, the stores and restaurants should be ready by late summer or early fall, says Trey Salinas, who represents 35/435 Investors, L.P., the project's development partnership made up of Don Martin, Bill Smalling, and Bill Boecker.

Acevedo, who resides on the east side of La Frontera, only yards away from Round Rock's industrial park, a marker for the city's ETJ line, never had to deal with Austin's annexation whims. He says his property taxes, which totaled about $570 in 1999, haven't risen much since the Seventies, but he fears they'll soar once La Frontera is complete. Northridge Acres' residents, whose children go to Round Rock schools, already have to contend with one of the highest district tax rates in the state.

La Frontera's developers spent about $30 million on their 328 acres of land across the road from Northridge Acres, Salinas says, adding that the developers probably wouldn't consider purchasing the land Northridge Acres occupies since the property is in Austin's ETJ, he says.

"That makes a big difference in terms of what you can do," says Salinas, referring to Austin's notoriously stringent development rules. "In all honesty, we'd prefer to stick to Round Rock." Salinas was an aide to former Austin mayor Bruce Todd.

Northridge Acres residents wouldn't mind being a part of Round Rock and have made requests for the city to annex them. Not surprisingly, residents weren't pleased when Round Rock decided to annex La Frontera, whose Marriott alone will generate about $1.5 million annually in taxes. "It is not fair to bring them into the city limits and not include Northridge. After all, we have been asking for help from Round Rock for years," wrote Snyder in a protest letter to the city.

The tall chainlink fence separating the industrial park and the condominiums from the subdivision screams the city's answer.

"The council doesn't believe they're in the best interest of the city as a whole," Nuse says. "We're not interested." Travis County Judge Sam Biscoe, who was the driving force behind the county's decision to help Northridge Acres with its water hookup fees and who has worked to get grant funding for projects in other local substandard communities, explains why. "The problem with the cities is they're kind of revenue conscious. The residents of wealthy communities are annexed a whole lot faster than the poor ones," he says.

Janie Rangel, co-chair of People Organized in Defense of Earth and its Resources (PODER), an environmental and social justice group, agrees. "They're building and developing everywhere. Why not help your own people out before you bring in someone else?" she says. "I for one would like to see the cities spend more time and money on them. The money is out there. It's just who's holding it and for what?"

Round Rock found a way to waive about $100,000 in building fees for its new Marriott, including the charge for tying into the city's water and wastewater system. "You have to pay for the right to tap into that system," Salinas notes. Mark Borskey, chief of staff for state Rep. Mike Krusee, R-Williamson County, sums up the predicament of countless Texas colonias when referring to Northridge Acres. "Everybody has a responsibility to somebody else, and Northridge Acres has been caught right in the middle. It's caught in this no man's land and it shouldn't have been."

One suggestion Ward, the UT professor, makes at the end of his book for dealing with substandard development in Texas is to hold cities more accountable for colonia integration. He argues that Texas' traditional response to substandard developments -- to shun them, or deny that they even exist -- has been counterproductive, and that Texas should look to Mexico, a poor country with hard-tested public policies pertaining to substandard development. "The tradition has basically been learned from Mexican housing projects, that's why there's so many on the border," he explains.

Even if no municipality wants Northridge Acres, resident Snyder for one has his fingers crossed that someone else will. "It's hard to replace what you've got. I ain't going to give it away. It's going to take $200,000. But if they'll pay my price, I'll sell it." ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.