https://www.austinchronicle.com/news/1999-01-22/521047/

Death Row Dilemma

Resistant to Change

By Erica C. Barnett, January 22, 1999, News

In federal court, two death row inmates -- Danny Lee Barber and Joseph Stanley Faulder -- took advantage of a recent Supreme Court ruling called Woodard v. Ohio Adult Parole Authority, which gave the judicial branch the authority to review due process claims, to claim that the board's "arbitrary and capricious" procedures violated their right to due process. In that case, Sparks ruled that although "the Texas clemency procedure is extremely poor and certainly minimal," it meets the standards for "minimal due process" as established in the Supreme Court case. However, Sparks suggested in his ruling, the board could prevent future challenges to its clemency procedures "by simply adapting the current procedures to require members to succinctly state their reasons for recommending or not recommending clemency." Currently, the form which board members use to fax in their votes on clemency matters is a simple ballot, with lines for board members to sign indicating their recommendation.

The ruling did nothing to change the board's procedures, but the hearings did create a few important precedents. For one thing, it was the first time board members had ever been called to testify about their procedures in court; the testimony of a dozen board members provided the clearest picture yet of the board's clemency procedures. "Just having a hearing and having the board members come in and testify and expose the farce that is clemency in Texas is very significant," said Minneapolis attorney Sandra Babcock, who is representing Faulder in his death row appeals. All the members (except board chairman Rodriguez, whose testimony Judge Sparks called "suspect") testified that they usually do not read every page of an inmate's clemency petition; often, they testified, they vote on clemency matters before even receiving all of the relevant information -- such as, in Faulder's case, a letter from Secretary of State Madeleine Albright imploring Gov. Bush to grant a stay. Some even admitted that they took only a few hours to review Danny Lee Barber's file, a stack of papers over four inches thick. "It's insulting to me that they're making life and death decisions on the cases when they don't carefully consider the evidence," Babcock says.

Moreover, the federal court case showed clearly that board members and their staff workers make mistakes; in the case of Faulder, a Canadian on death row who was never allowed to contact his consulate, and whose existence was concealed from Canada for 15 years in violation of the Vienna Convention, those mistakes included the omission of at least 10 significant letters from his clemency petition file. Those documents included letters from Faulder's friends and family members, a letter from a church association representing 10,000 Texas congregations, and several missives from doctors and the American Bar Association disavowing the testimony of Dr. James Grigson, aka "Dr. Death," who was disbarred from the American Psychiatric Association for testifying falsely in dozens of cases about the future dangerousness of convicted murderers. Grigson's testimony, lawyers say, was a crucial factor in Faulder's death sentence; if board members had known he was disbarred, they contend, they might have decided differently on his clemency petition.

Another thing that was abundantly clear after the two days of hearings was how little formal guidance board members receive in making their decisions. "There are a lot of things you consider in each case, because each case is very different," said board member Sandie Walker in her testimony. "I don't think you could set out guidelines. ... I think that's why we have a board. There are 18 of us and we all bring our life experiences and all the choices we have made in our life and all of these things come to bear on our decision." Board member Daniel Ray Lang, a criminal defense attorney, was even more circumspect: "You can't really define justice and mercy, but when you see it, you know it," he said. "It's an abstract concept." Lawyers for the inmates say this lack of guidelines is exactly why the board, whose members receive only one week of training to prepare them for the 59,000 parole cases and 400 clemency petitions they will be faced with every year, needs to meet in public and establish criteria for its actions. "It seemed to me in listening to their testimony, the only thing they look at is whether they had a trial, and other board members only look at whether the person is guilty or innocent," says Babcock. "Historically, it's been about mercy and redemption and rehabilitation, and these board members have no concept of those philosophical ideas."

|

|

Overwhelming evidence suggests that one philosophical idea -- mercy -- plays little role in most board members' clemency determinations; but death row attorneys insist it should. If a death row client is not innocent -- and Barber's attorney Kurt Sauer acknowledges that most are not -- the only reason the board might grant clemency is mercy, which Sauer says appears to be in short supply. "If there's a question about guilt or innocence or somebody hasn't gotten due process, we're not showing them mercy by granting them clemency. We're doing something that only a barbarian would do otherwise," Sauer said in court. "If Ms. [Karla Faye] Tucker didn't get it, we don't have it."

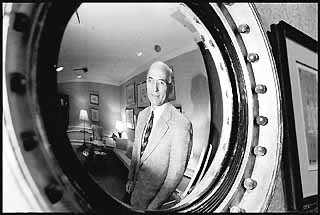

Victor Rodriguez, who testified at length in Sparks' courtroom, counters that the board is willing to consider any information submitted in a clemency petition; the challenge, Rodriguez says, is convincing board members that a guilty death row inmate deserves mercy, which he views as an act of grace. "Our responsibility is to consider the petition -- if they argue rehabilitation, improvement, religious conversion, it is considered," Rodriguez says. "They've argued all kind of things before us. Some have been successful. ... My job is to look at the question of the case and decide it in the best possible way. It is not my fault that they have not presented good enough cases for clemency."

Argument Rejected

Sparks' rejection of the lawyers' claims sent the case catapulting into state court, where the lawyers had, they felt, a stronger legal case. This time, the issues were more clearly defined: Did the board violate the Texas Open Meetings Act by refusing to hold hearings and make its deliberations open to the public? and, did it violate the Texas Constitution, which states that "the Legislature shall by law establish a Board of Pardons and Paroles and shall require it to keep record of its actions and the reasons for its actions"?

The lawyers for the death row inmates in the state class action suit pointed to the fact that the board members' clemency voting sheets -- although recently amended to include a "comments" line -- do not require board members to provide reasons for their actions. This makes filing a clemency petition virtually impossible, lawyers said, because they have no idea what criteria the board has considered when it denies clemency; moreover, since no investigation is done, board members have no way of verifying whether the information in a petition is accurate, leaving that assessment at the whim of the member reviewing the petition. The state's attorneys, led by assistant attorneys general Reid Lockhoof and Dewey Helmcamp, countered that the board only has to give "written recommendation and advice" to the governor, as required in the constitution, when it votes to recommend clemency -- not when it chooses to maintain the status quo. Further, they said, the state's government code says that board members "are not required to meet as a body to perform the members' duties in clemency matters."

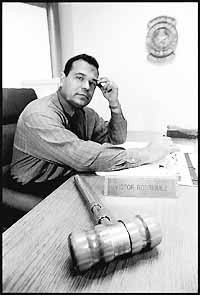

Although Kurt Sauer, representing the death row inmates, argued that McCown should consider the legislative history of the law, which was amended specifically "to not exempt clemency actions from the open meeting law," the judge sided with the parole board, agreeing that the constitution "does not require the board to give reasons when it denies clemency because in such a circumstance it has taken no 'actions.'" Moreover, McCown's ruling said, the Legislature provided the board with "a big loophole" in allowing it to avoid meeting as a body; "if no meeting is required, no open meeting is required."

Board members were buoyed by the ruling, which upheld all of their longstanding claims. Board chairman Rodriguez says that although "there are things for which we are subject to open meetings. ... We are not like any other entity in the state in the sense that we are not required to conduct board business in public." But that's no different, Rodriguez says, from the secrecy maintained by a jury or, for that matter, the Supreme Court. "God only knows what goes on inside that jury room. They don't meet in public. There are reams of information presented to them in the Supreme Court and they just say no. They don't have to explain." Lawyers pick on the board, Rodriguez says, because the courts allow them to. "I don't see them taking Judge A or Judge B to task, saying they didn't get to come and speak before them," he says. "I don't see them complaining how bad these guys are, how they wouldn't let them speak before the jury ... I am at odds to explain to you why they do that." The board, whose members unanimously testified that they feel more comfortable making their decisions individually and without deliberation, has only held one public hearing, called by then-Gov. Ann Richards in 1992 to address questions in death row inmate Johnny Garrett's case which had never come out at trial.

Secrecy Rules

For the time being, it looks like the board's secretive process will continue; an appeal is possible, but lawyers on the case say they don't know yet if they will attempt to make one. Unlike two previous state court rulings, McCown's decision places the onus of changing the clemency system on voters, not the courts, leaving the lawyers on the case little wiggle room for any future legal maneuvers. "It belongs to the citizens to express their judgment through their assembled representatives in the 76th Legislature as to whether this system adequately ensures that Texas is able to determine when mercy should be given," the ruling says. Attorney Maurie Levin says the ruling smacks of political considerations. "Our judges are elected, so you can never discount the fact that politics play a part in their decisions," she says. "Judge Sparks' decision was a much stronger decision, and I think that has to do with the fact that he's not elected." The decision was at the very least a crushing blow for those battling for an open clemency process, made all the more painful, Levin says, by the fact that McCown seemed ready to rule in the lawyers' favor. "It's hard not to believe you have a chance when you feel that the law is behind you so strongly. I should have known better by now," says Levin, who has argued state and federal capital cases for years. "I was so mad at the decision. ... He led us to believe he was doing something else. Even the state thought we had won."

There are a few hopeful signs for death row inmates and their lawyers, though those are few and far between. Board chairman Rodriguez has indicated, as he has in the past, that he is warming to the possibility of making minor changes to the board's procedures. "We want to do everything we can to make sure we are as close to what (Sparks) wants as possible," Rodriguez says. According to the board's assistant director Hugh Campbell, several changes are planned for the next three months, including further modifications to members' voting forms and the installment of a statewide computer network that will allow board members instant access to clemency petitions and supplemental information as they arrive.

Meanwhile, public opinion appears to favor a more open process; the state's major dailies have all printed editorials chastising the board for its refusal to adhere to open meetings law. And former attorney general Dan Morales, as he was leaving office, told The Dallas Morning News that he thought the system could be constructively changed. "There's no question in certain cases that the process does not appear to be an absolutely fair and equitable system," the paper quoted Morales as saying. On the whole, however, the balance of court and governmental opinion weighs heavily in the parole board's favor. Governor Bush has stated repeatedly that he supports the current system, as long as doubts about guilt and whether the inmate had access to the court system are resolved. And new attorney general John Cornyn, who criticized the parole board's decision to commute Henry Lee Lucas' sentence during his campaign for office, has indicated that he, too, supports the current system. "We believe the procedures are in keeping with the state constitution and the federal constitution," says Cornyn's spokesman Ted Delisi. "[Cornyn] is the state's top lawyer and is supposed to enforce the laws as the Legislature sees fit. ... He will represent the state" in court, Delisi says.

The battle, inmates' lawyers say, is far from over; they will continue to fight for their clients in the courts. But even death row attorney Sauer admits that it will take a legislative remedy, not a judicial stopgap, to stop the current rubber-stamp rejection process in its tracks. The question, Sauer says, is "until that happens, what do we do? Do we make them follow the laws and have open meetings until someone decides to do something about it, or do we just keep killing people until we do something?"

Next Stop: The Lege

|

|

But others involved in the case say the effects of McCown's ruling are likely to snowball out of the judicial system and into the Lege. "I think they're damaged by the ruling," says attorney Jim Harrington, who intervened in the case on behalf of his client, Gary Graham, whose execution was halted by the Fifth Circuit last week. "You take away the sword over [board members'] heads when you say it's not unconstitutional. What's the incentive for the Legislature to do anything then?" Even if Naishtat's bills do pass, it is still unclear whether the state will challenge the Legislature's authority, because the board contends that only the executive branch has the power to regulate its actions. Although Naishtat says the state's lawyers have given him no reason to expect a challenge, he acknowledges that much of the decision is in the hands of attorney general Cornyn, who supports the current procedure.

Naishtat's legislation won't be the last time death penalty issues come up this session. Already, a bevy of capital punishment-related bills wait in the wings. One bill by representative Pete Gallego would prohibit the execution of inmates deemed "mentally incompetent" by a doctor; another by Eddie Lucio in the Senate would create a true "life without parole" option for jurors to consider. If that bill fails, Naishtat has filed a bill in the House which would allow lawyers to tell juries that an inmate sentenced to life in prison will not be eligible for parole for a minimum of 40 years, a power that defense lawyers currently do not have.

Death row defense lawyers like Sauer and Babcock say they're not holding their breath for legislation to pass; in their world, "hope" is a word used only sparingly, in reference to 30-day reprieves and last-minute stays, never permanent solutions. With a client survival rate that hovers around 1%, Babcock says, "You just end up walking around angry all the time. It just seems so hopeless. It's hard to keep your energy up when you've just lost another client."

Nevertheless, Sauer says, the fight will continue beyond the most recent round of court rejections. Even if an open process would not spare, in the short term, a single inmate's life, Sauer says the value of open government is greater than that of any individual case. "The thing that really bothers me is, you've got a state agency being paid taxpayer money to keep its decisions secret from the taxpayers," Sauer says. "In every city council, every government body in the state, some 50-person town -- you know, Dancer, Texas -- they all follow this [open meetings] law. Only the board doesn't. What they're doing could not be so important that they don't have to comply."

Copyright © 2024 Austin Chronicle Corporation. All rights reserved.