https://www.austinchronicle.com/news/1999-01-15/521006/

Blueprint for a Breakdown

Not Worth the Work

By Kevin Fullerton, January 15, 1999, News

|

|

"We're not bidding any more bond work with [AISD]," says David Bandy of D.L. Bandy Constructors, which just completed renovation work at Allison Elementary. "For the effort we expended, there was nowhere near the return there should have been." Bandy, whose job was delayed three weeks while he waited for confirmation to relocate underground water lines which were in the way of his workmen, says he managed to get paid for expenses caused by the holdup only after "considerable arguments and hassles." If he were to bid AISD again, Bandy says, he would need to hire an additional full-time employee just to process the paperwork, and would up his price 6-8%. "That cost increase has less to do with the market than it does with the people running the [AISD] program," Bandy says.

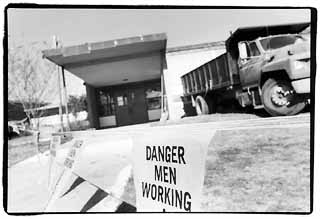

Smaller and midsized builders such as Bandy have had the most difficulty working with BLGY/Sverdrup because they have less working capital to compensate for the slowed payment schedule, delayed decisions, and stringent safety compliance that the construction management company has imposed on them. But larger contractors say AISD has slipped lower on their preferred client list, too.

"Because the construction market is strong, we can be fairly selective about the work we pursue, and right now we prefer to pursue work other than AISD," says Russell Garner, vice president of the $30 million-dollar Browning Construction. Garner says BLGY/Sverdrup acts as a "filter" between AISD and general contractors, which adds the potential for complications. "When we cannot communicate directly with the owner, we may prefer not to participate because that's less desirable. ... That's a negative for AISD as far as I'm concerned," says Garner.

"AISD was always one of the more friendly bureaucracies, until recently. Now it's become one of the toughest to work with," agrees another large contractor, currently working on several AISD sites.

BLGY/Sverdrup, however, is not without its defenders, including AISD staff and architects hired by the company, who say that the construction manager has accomplished a great deal in a short period of time, and that only a private company could move at the pace necessary to complete nearly 200 projects in four years. School and BLGY/Sverdrup officials say it was inevitable that not everyone in the construction community would like the company's business style. AISD construction manager Curt Shaw says that while drug testing, safety considerations, and ROCIP add layers of bureaucracy, they also add benefits that contractors encountering the system for the first time don't immediately recognize. "There's guys that will say, 'I'm not peeing in a bottle for anybody, and as long as that's a piece of the requirement, we aren't going to do any more work for [AISD],'" says Shaw. And while larger contractors aren't bothered as much by BLGY/Sverdrup's style because they already incorporate precautionary rigmarole in their own business and are used to it, Shaw says, "guys that bid work in the half a million to a million-dollar range, it's a different ball game for them. ... They just don't like to operate that way, and I can understand that completely." Shaw believes stories about unhappy builders are overstated, but he admits that "there are probably more than you'd want in that category."

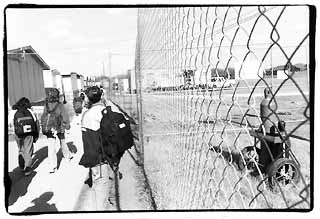

But how is it that we now count the exclusion of small businesses from the bond construction process as an acceptable casualty? The BLGY/ Sverdrup program was sold to the AISD board as a means of including a wider diversity of businesses, and AISD is paying $3 million as part of the construction manager's fee for a HUB program. And the truth is, many builders have taken on contracts with AISD for the first time in this bond program. The harsher truth, however, is that some of those smaller companies wish they hadn't. As Shaw noted, they haven't taken well to losing employee workdays to urine tests or safety classes, nor to having their crews hassled by inspectors for not wearing hardhats while eating lunch or sent home because scaffolding was damp.

"I'm all for safety," says one subcontractor who asked not to be identified because he fears he may never get paid for change orders he performed on an AISD site, "but I've worked on nuclear plants, I've worked industrial, and I've never seen a safety program to the extent they've got. I think it's ludicrous."

Delays Too Common

|

|

But the headaches and delays suffered by some contractors on AISD sites cannot be so easily dismissed as the mere result of a "no sympatico" business relationship. In his northeast Austin office, general contractor Keith Hutchison displays a list of 63 change orders for work on Pease Elementary, dating from the first day he was scheduled to begin remodeling and additions, March 2. The change orders -- which represent unanticipated expenses Hutchison encountered on his job for which he is contractually entitled to be reimbursed -- total more than $120,000, a cost escalation of 10% on the $1.1 million Pease job. Hutchison says getting those change orders approved and paid out by BLGY/Sverdrup has been an exercise involving "many battles, lots of tears, screaming, and fighting," and that the resulting delays have turned a project scheduled to last six months into a 10-month Chinese fire drill. "I have no qualms with AISD," says Hutchison, "but I'll think twice before working for Sverdrup again. ... Their entire attitude and lack of planning is just ridiculous."

Hutchison suffered an immediate two-week setback on his first day onsite at Pease, when he discovered that his job had not yet been permitted by the city. Once work began, Hutchison found that the architectural drawings were not complete, confronting him with numerous ambiguities or errors for which clarification and change orders had to be requested. And on almost every item, Hutchison says, no matter how small, from wrapping air ducts to installing grease traps, it took Sverdrup weeks to respond. The most jaw-dropping of unpleasant surprises, however, was when Hutchison discovered that the building was not fitted with the steel beams necessary to support a planned new elevator shaft, nor was the requisite steel on-site. Hutchison lost weeks while an engineer drew up a plan, pricing was approved, and the material finally shipped. Meanwhile, he says, unfathomable delays getting answers to relatively simple mechanical problems in the school's kitchen delayed its opening past the first day of fall semester. Students ate sack lunches from home in the meantime.

"You don't hear anything from them until it's a crisis situation," Hutchison says of the construction manager team. "Then all of a sudden, you better get out there immediately: 'Overtime! Get on it! Why haven't you started?' Then they turn around and say, 'You didn't meet the schedule.' Well, no kidding I didn't meet the schedule with 63 change orders to deal with." Hutchison says he still hasn't been paid for the time lost on the initial permitting problem, and that, after agreeing in August to allow him to make change orders at will to speed the schedule, BLGY/Sverdrup is now balking on payment for those changes. "They told us to go for it," says Hutchison Construction's project manager at Pease, Fraser Gorrell, "and we jumped through hoops. Then, after we were done, they started nitpicking the pricing."

Further north, at Brykerwoods Elementary, builder Bill Holladay, owner of Wi.C.H. Company, experienced similar difficulties that forced him to run 45 days on costly overtime to finish on schedule. He has been waiting two months for nearly $300,000 in payments, he says, but is not sure whether BLGY/Sverdrup will ever pay full recompense for his overtime, even though he kept careful records. "My profit's gone, and now I'm pulling it out of my pocket," says Holladay. Like Hutchison, he suffered an initial delay, more than a month, waiting for site permits, then had to take an unwanted two-week furlough for asbestos removal. His biggest headache, Holladay says, was a lowered ceiling which an architect told him to install, not knowing, apparently, that accountants at BLGY/Sverdrup had scrubbed the ceiling to cut costs. Holladay did the job at a cost of $10,000, only to be informed later that he had erred and would not be paid for it.

But if the job delays and payment haggling hurt Wi.C.H. and Hutchison, they cut even deeper into the pockets of smaller subcontractors carrying much less reserve capital to bank on. "It's just a fiasco," says one subcontractor. "People are dragging their feet because they're not being paid. ... Because of the money crunch, every time we found a mistake and went back to get it rectified, they didn't want to pay it. ... We've thought seriously about pulling off the project; it would be cheaper for us to quit."

The blueprints for the projects at Pease and Brykerwoods elementaries were both produced by the same architectural firm, Coffee, Crier, and Schenck, which declined to comment for this story. But Hutchison and Holladay say they don't blame the architects for their projects' design mistakes, saying rather that the architects' ability to properly review their plans and oversee the construction phase was undermined by sharing responsibilities, and fees, with BLGY/Sverdrup. Jerry Hammerlun, a project director at the architectural firm O'Connell Robertson, says the BLGY/Sverdrup practice of reducing architects' participation in the construction phase doesn't tend to create positive results. "What you're doing is taking the group that designed the project, and knows the guts, the building, inside and out, and bringing in somebody who doesn't ... when there's lots of critical decisions and issues to resolve."

Process Flawed

|

|

Architects and contractors' work has been complicated by the "value engineering" process that has become an almost standard cost-paring exercise in this bond program as budgets for a great many campuses run overbudget. Hammerlun says Sverdrup brought in a design process which, in theory, should have closely matched projects and pricing in the early stages, preventing costly modifications later. But on some projects, he says, BLGY/Sverdrup failed to address cost problems that were looming, leading to last-minute adjustments that opened the doors for errors, delays, and confusion.

Sverdrup's strategy was to bring architectural/ engineering firms and general contractors together earlier than usual, when projects were about half designed, to prevent surprises on cost. But Hammerlun, whose firm has designed several current AISD projects, some of which have suffered prolonged budget overruns, says the construction manager failed to act proactively when his company flagged severe budget discrepancies early in design.

Architects say BLGY/Sverdrup delayed delivering the bad news on troublesome projects to AISD, instead letting projects move on to construction phases and planning cost cuts down the road. Everyone rolled along fat, dumb, and happy until contractor estimates came in and budget realities hit the pavement. Then came the scramble to "value engineer," or strip projects down to more basic specifications. Hammerlun says if budget problems had been addressed early on, rather than after builders contracted for the jobs, some paring down might have been prevented. "Their pencils aren't as sharp once they've been awarded the contract as they are when they're trying to get the contract," Hammerlun says of general contractors. "That's just the nature of the beast. When you make changes after the contractor is on-site, either the price is going to go up or you're not going to get as much credit back, maybe only $8 for $10." If $400,000 in cuts are made on paper, Hammerlun says, as much as $500,000 in actual value can be lost. Some sites have had budget overruns in the millions, which, multipled by 45, the number of AISD projects currently over budget, can add up. The amorphous nature of projects being value engineered can also cause builders to back away.

One contractor, after reviewing the plans on one particular middle school project and watching the constant design changes and confusion already in progress, walked away. "We didn't just say no," he comments. "We said, 'Hell, no.'"

In the last few months, bidders for renovation work have been scant; it's not unusual for the district to receive only one or two bids per project, and those have sometimes run 30%-100% over budget.

Sverdrup Speaks

|

|

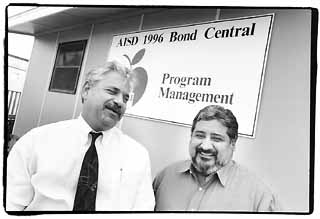

BLGY/Sverdrup executives did not have a chance to respond to the specific problems detailed in this article, but program manager Mitchell Gershen and deputy program manager Jerry Jaramillo spoke with the Chronicle for an hour and a half addressing the general complaints being made against their company. Gershen and Jaramillo say the AISD bond program has been a unique challenge that their company needed time to adjust to. Responding to questions as to why AISD projects have strayed so far from their budgets when their own company was paid millions to scope them to budget before the bond construction officially began, the BLGY/Sverdrup execs said active involvement by parents and school officials led to various interpretations of what had been promised at individual campuses. Sorting out what was acceptable to everyone took time, they say, and meanwhile, the hot construction market was making initial projections more and more unrealistic.

"So when you have that tug of war on budget, and yet people's expectations are high, plus the economy impacts, etc., sometimes you have to stop, call time out, regroup, and problem-solve," says Jaramillo. Many projects ran smoothly, they point out, and the first third of the program came in within 1% of the budget. AISD construction manager Curt Shaw agrees that "the ground shifted" under BLGY/Sverdrup after it accepted the AISD contract. But he admits that Sverdrup's lack of familiarity with AISD and the wider community made it that much harder for them to get in synch. "New AISD staff would have had a learning curve, too," Shaw says, "but there's a kinship that occurs with having district personnel handling some of those issues rather than a hired gun." School board president Kathy Rider says she sympathizes with BLGY/Sverdrup's difficulty negotiating with campus task forces who "thought they were going to get chocolate ice cream and instead got vanilla."

Asked about the bureaucratic delays and miscues that contractors are complaining about, Gershen replied, "Your comment is valid as it relates to the past. Yes, we let delays happen and created problems, but we're attacking those issues with a vengeance." He gives as an example a new arrangement with the city of Austin that has eliminated site permitting holdups. And Jaramillo adds that while many contractors are used to dealing directly with a single AISD manager and may be frustrated at the slower pace of BLGY/Sverdrup's process, the payoff for the district and taxpayers is strict accountability and coordinated direction.

Some architects involved with the AISD bond package say that while the BLGY/Sverdrup machinery has turned too slowly, they don't think the company is incompetent or unconcerned. They say if the company is guilty of anything, it's trying too hard to please their client, and not dealing firmly with AISD when the district added educational specifications to projects that made campus budgets unrealistic for the size of the bond package. "Sverdrup was determined that they were going to get this done and everyone was going to be happy," says Andrew Vernooy, of Black/Vernooy Architects. "They didn't go back to the board and say, 'These things cost extra.'" Carl Holiday, a project team member for Vernooy, adds that Sverdrup failed to negotiate a contract with AISD that gave the company true decision-making authority. "They're given the title of vicar, but they don't have the authority to actually be the vicar," says Holiday. "That was a fatal flaw." Meanwhile, Vernooy says, AISD made a mistake in firing all but one of its construction managers, throwing out institutional memory that Sverdrup sorely needed. "It would have paid to have kept those people on staff," given the time that's been lost to errors, Vernooy says.

School board president Rider says that BLGY/Sverdrup wanted to come to the board and begin reporting problems long before the meeting in August, but that school superintendent A.C. Gonzalez had refused the company access. Gonzalez replies that it's a "misperception" on the board's part to believe his office "bullied" the construction manager into withholding information from them, saying monthly meetings BLGY/Sverdrup has held with the board-appointed citizens bond committee since the bond projects began provided plenty of opportunity to hear the company's reports. It wasn't until August, however, that AISD staff and BLGY/Sverdrup sounded an alarm, when "we totally understood that the levels of difficulty had reached a point where we were unable to resolve them without getting more dollars," says Gonzalez.

For its part, Sverdrup says that the deal it made with the school district -- which gave it the role of "construction manager," meaning that AISD, not Sverdrup, held builders' contracts, rather than "construction manager at-risk," in which contractors would have signed directly with the company -- wasn't the arrangement the company preferred.

"What we got was a mechanism with no way to ensure that, at critical moments, there would be someone with the balls to say, 'You know, we screwed this up and we need to come clean right now,'" says Holiday.

Lessons to Learn?

|

|

But even if many are unwilling to blame BLGY/Sverdrup alone for the misery and disappointment that has plagued this bond construction, it remains true that hiring Sverdrup has been no bargain. The notion that importing a private bureaucracy to place atop a public one has cost the school district, the building community, parents, and students both money and frustration. Those looking up into the belly of the beast -- contractors like Hutchison and Holliday and the various subcontractors who have struggled to stay afloat while working on AISD projects -- have borne the cost of Sverdrup's learning curve directly. It's hard to say what further delays or cost overruns will be caused by subcontractors avoiding AISD job sites. "I can't get subcontractors to do work for us, because they say, 'Well, we haven't got paid from last time,' so my position gets muddled a little bit," says Hutchison Construction's Gorrell. Asked if his company has perhaps tried to balance campus budgets on the backs of contractors by haggling over reimbursements for change orders and delays, Gershen said that he "absolutely would not tolerate that." But builder Holladay's experience, especially, seems to indicate that even if the construction manager means no harm, its tight-fisted accounting, now being applied after so much has gone wrong, is placing the cost of those mistakes on the wrong people.

"AISD did not give consideration to the size of the entity they were creating and how it would affect those of us in the industry," says a contractor. "It locks these jobs up because we can't get subcontractors that want to deal with it." The contractor says if he could point to one feature of the Sverdrup process that's especially onerous to smaller builders, it's the ROCIP insurance program. He says complying with the insurance can increase an employer's correspondence tenfold over what he's accustomed to. AISD staff and BLGY/Sverdrup executives held two forums last summer at which builders clamored for an end to ROCIP, but the program remains in place. The intent of an owner-administered insurance program was to make AISD projects easier and less costly for smaller builders to participate in, but subcontractor Lee Roy Anderson says as far as he knows the program doesn't save either builders or the school district money. Far from allowing AISD a credit for providing them insurance, Anderson says, most subcontractors increase their prices when bidding AISD to offset extra administrative costs.

Many contractors begin their frustrating accounts of working through BLGY/Sverdrup with the preface, "In all my (15, 16, 23) years, I've never seen anything like this." But Anderson, a plumber since 1973 whose firm Fox-Schmidt has a long and happy history with AISD, does remember a similar situation. That's when Round Rock hired a "construction manager" to build some schools in the late 1970s, Anderson says, and the result was a lot of bankrupt subcontractors. "I mean, you find one of these construction management programs that works right, and it's a miracle," says Anderson. Construction management might work for private companies, he says, but it's not right for a public program.

"Contractors from Austin that I've dealt with over the years ... they've just refused to bid the [AISD] projects, said, 'We're not going to look at them. It's not worth the hassle,' " says Anderson. Anderson himself has paid a price for dealing with AISD this time around; he's currently working overtime to keep pace with concrete work that has been accelerated due to initial delays from the ubiquitous site permitting problem. Anderson has been told flat-out that he cannot collect on the additional expense.

"Some of the grumbling and complaining can probably be chalked up to this just being a different way of doing things," says Rider, "but when you begin to hear it all across the city ... something's not cricket."

One thing seems certain: If AISD chooses to hire a private construction manager for future bond programs, it may get more bells and whistles -- some of them, like the HUB program, not insignificant -- but it will pay a premium price for the service. Asked why surrounding school districts are now paying less for their construction than AISD, BLGY/Sverdrup's Gershen replies testily, "I guarantee you we're not using the same materials and systems as some of those other folks. ... It's not the same building, my friend, and I can say that with conviction." Del Valle director of facilities Crook, however, insists that the district's buildings are in fact as good, if not better, than AISD's. And his statements are confirmed by AISD staff and contractors who bid with Del Valle.

"We're building what AISD used to build," before this last bond program, says Crook. "I'll put 'em up against any AISD building."

So that's what Sverdrup, even if their intentions were for the best, has brought to AISD: an alienated building community and higher prices. It's ironic to note, of course, that if AISD had continued through the construction with former superintendent Jim Fox, whose idea all this was from the beginning, Fox's propensity for tight control might have helped Sverdrup work more efficiently. But as architect Vincent Hauser points out, an overly efficient process is not necessarily compatible with the "nature of citizen participation." For now, Hauser suggests, the best thing for the school and construction community to do is "think about how we're going to do the work that's left in the best possible way. What do we do now in order to make things better?" To their credit, BLGY/Sverdrup has shown that they're willing to regroup, address problems, and deliver the goods. Superintendent Gonzalez reports that payments to contractors are being processed more quickly now, and that AISD will do what it can to prevent more holdups.

But next time around, if AISD feels that a bond project is bigger than it can handle, perhaps it would better serve itself by concocting smaller bond packages and taking longer to do them. Maybe some community challenges just aren't amenable to a corporate solution.

Copyright © 2024 Austin Chronicle Corporation. All rights reserved.