Honky-Tonk Soul Man Charley Crockett Makes His Move

The singer's long road to Austin

By Doug Freeman, Fri., Dec. 14, 2018

Last week, Charley Crockett released his fifth album in four years. Come early January, the 34-year-old country soul singer will undergo open-heart surgery.

"I've had a hernia for seven years, and I didn't do anything about it because I didn't have insurance," offers the Austinite. "This last year of touring, it really started bothering me onstage."

Preparation for that procedure this past summer revealed he had Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome, a fairly common congenital heart condition. A visit to the cardiologist revealed an even more dangerous abnormality: Crockett's heart only has two valves.

"My heart and aorta [are] enlarged because 30 percent of my blood is flowing back into my heart between heartbeats since I'm missing a valve," he explains. "I've been getting really dizzy randomly over the past year, and really tired. I thought it was just that I was playing 200 shows and traveling in a van and not getting any sleep, but the doctor said, 'Nope, your heart is slowly shutting down because it's overworking.'"

Crockett conveys the news with a sense of wonder and inevitability, as if the strange circumstances leading to his diagnosis happened to someone else. Whether out of denial, survival, or sheer determination and optimism, he refuses to allow the impending surgery to slow his roll because, for maybe the first time in his life, the tides are turning his way.

Sitting at a small kitchen table in the cozy East Austin house he shares with his girlfriend Lyza, the Texan is typically calm and unhurried but speaks with an excitable, unbridled energy. One thought barely finishes before the next one leaps in. He ponders through answers unsure of where they might lead, as if he's trying to describe a new color no one's ever seen.

His songwriting compels with the opposite effect – precise and direct. He burrows into a bluesy simplicity soaked in suave, soulful vocals, melting heartache in a distinctly lisping delivery. This year's 4-star fourth LP, Lonesome as a Shadow (see "Texas Platters," May 11), marked Crockett's best thus far, shades of Louisiana and Texas baked into his unique honky-tonk blend.

"I'm recognizing that one of my challenges is they're having a hard time pinning me down, and what's interesting about that, to be candid, is that often if they can't pigeonhole you, that hurts you," he admits. "They want to be able to understand your sound. And look at me, I'm all over the map."

Crockett's accent rolls in a deep Southern drawl, but with a sharp clip to his phrasing, more New Orleans than his hometown of San Benito in South Texas. Onstage, he's a figure drawn from another era, dapper suit and stiff cowboy hat to match his throwback sound, but with a wily energy erupting in his shimmies and shakes. His sets seamlessly meld honky-tonk deep cut covers and bluesy soul originals that bend time.

No surprise, then, that after years wandering across the country, the troubadour finally settled locally, where artists from Doug Sahm to Gary Clark Jr. have carved success through unconventional evolutions of traditional forms. Although Crockett still plays only a handful of local shows every year, he's gaining national attention with backing from influential Nashville booking agency Red 11 and a distribution partnership with powerhouse indie imprint Thirty Tigers. This past summer, he wowed festival crowds at Portland's Pickathon (see "Playback," Aug. 10) and Austin City Limits.

So instead of taking his impending surgery as a setback, Crockett considers the diagnosis a stroke of luck, arriving now that he has insurance and some money in the bank.

"They told me I'd have been likely to have heart failure in the next 12 to 36 months," he says. "If I didn't have that hernia, I would have never even found out about it."

How Long Will I Last?

Charley Crockett is tired of running.

Before settling in Austin three years ago, the troubadour spent over a decade living rough on the road, his guitar and restlessness the only constants in his life.

"My mom got me a guitar from a pawn shop in Irving when I was 17, and that's when I started playing," he allows. "I didn't ask for that guitar. I think my mother knew that life was hard. I think she knew that I was alone most of the time. I wasn't seen as gifted in a lot of ways, but she knew I was highly creative. I taught myself how to play and started to write songs immediately, without any chord knowledge or anything.

"I didn't know what key I was in for 12 years," he laughs. "But my ear was really good, and I could play in any key and any chord. I just didn't know what it was."

Growing up in Dallas with his single mother and spending summers in New Orleans with his uncle, Crockett didn't like his options coming out of high school. He hit the road at 17, trying to find a different path.

"At first, I floated around," he says. "I was determined not to be a part of mainstream society. I tried to stay outside of the limited choices I saw for myself. I remember the first time I slept under a staircase in a park, and how scared I was. When I woke up the next morning, even though I'd only gotten a couple hours of sleep, the sun still came up."

In Northern California, Crockett worked on communes and farms. He busked the streets in New Orleans and Memphis. He ran the subways of New York City, sleeping in abandoned warehouses. He was constantly in trouble with the law, existing in an itinerant world. Homeless in plain sight, he finds those years difficult to explain. And yet that blur of highways and train cars and cities revealed to him a different side of America: a country in the shadows of increasing poverty and struggle.

"If you're not working a nine-to-five like everybody else, you're seeing what's actually happening," he says. "That's what makes artists so powerful, so dangerous to the establishment. One of the only ways to be outside the system without breaking the law is to be an entertainer.

"If you listen to my songs, you're not going to hear a social critique, but listen to Lonesome as a Shadow and you're going to hear a record that's about a lot of pain and suffering," he continues. "People are really struggling and music that can help them relate to that struggle is the best thing I can do to empower people. That's what fuels me more than screaming about injustice, because nobody listens when you do that."

As he got better at his craft, he began organizing street bands in hopes of getting discovered. Oddly enough, it worked. Crockett caught the attention of a Sony representative while working the subways in New York with a collective of artists, and she signed him to a management contract. He balked at signing a publishing deal, though.

"It was one of those things where I would have basically signed over everything and plugged into a model that was already in place," he recalls. "I don't fault that at all, but I was homeless and living desperate, and had I been a little healthier and a little bit more clearheaded, I would not have signed it because I would have known exactly what it was."

Instead, he headed back to Northern California until the terms of the arrangement expired. He was 26.

"When I left New York, I knew I couldn't live on the street anymore," he says. "I was tired of it, and I just knew it was going to get me. I was becoming cynical. I was becoming too street. All I'd done my entire adult life besides play music was break the law."

Goin' Back to Texas

Charley Crockett is ready to make his move.

After three years working on the farms in California, Crockett returned to Dallas with a self-recorded album in hand and, to his surprise, found a burgeoning music scene.

"I had played in Deep Ellum when I was 18 and 19, but there was nothing going on," he says. "When I went back, it had blown up. I met Leon Bridges in 2014 before he kind of blew up, and we became friends right off the bat. The Texas Gentlemen were getting their thing together, and you could just really tell there was something going on in DFW."

He immersed himself in the local blues jam scene and played any bar that would have him. His CD, the aptly titled A Stolen Jewel, became his calling card. "If you looked at me, you got a CD," he laughs.

While making a living playing bars, he couldn't score bigger venues in Dallas because he played so often. He vowed not to make the same mistake here. Instead, he focused on recording and building a touring profile.

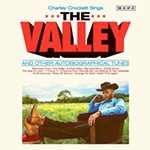

The result was a barrage of releases on his own label, Son of Davy – songs he'd written over the past decade but never recorded. In 2016, he offered up his sophomore album, In the Night, followed the next year by a collection of covers, Lil G.L.'s Honky Tonk Jubilee. This month's fifth LP, Lil G.L.'s Blue Bonanza, picks up the covers theme with takes on Ernest Tubb, T-Bone Walker, and a host of deep blues cuts.

"Lil G.L. is my side name, like Hank [Williams] had Luke the Drifter. I use it for all my side projects and cover projects," he explains about the moniker given to him by local blues drummer Jay Moeller in reference to obscure R&B singer G.L. Crockett.

"I think there's an over-emphasis on original material," he says. "George Jones and Loretta Lynn are amazing songwriters, but I would bet not a quarter of the material they put on records they wrote themselves. Hell, Ernest Tubb had 50 studio albums, not even counting live records."

It's an unorthodox approach to releasing albums in the 21st century; but then again, Crockett never took the obvious route. And it appears to be working. He's quickly built a fan base with a deep appreciation for his interpretations of past hits like "Jamestown Ferry" as well as his own exceptional material like "The Sky'd Become Teardrops."

"I don't have a normal mind," Crockett laughs. "When I was really young, I was seen as really slow and had speech problems and dyslexia, and all that. Which made it really hard on me, so it took me 10 times longer to figure out anything than anybody else.

"And maybe in the end, that's the story," he concludes. "I'm just that kind of person, that I have to learn shit the hard way. But maybe some of those things, for all the weaknesses they've shown in me, some of that persistence has ended up paying off."

The Crockett Catalog

A Stolen Jewel (2015) This lo-fi debut rollicks like a backyard barn bash. Harmonica and twanging strings feed haphazard harmonies, while Crockett's voice floats easily through the bluesy title track, the jazzy swing of "Bei Mir Bist Du Schoen," and the slow, slurring waltz of the Flying Burrito Brothers' "Juanita."![]()

![]()

![]()

In the Night (2016) Crockett finds his soul swagger on 2016's sophomore LP, horns blasting on the opening title track as he wails like Detroit street balladeer Rodriguez. A shotgun, Tex-Mex take on his hometown hero Freddy Fender's "Wasted Days and Wasted Nights" pops.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Lil G.L.'s Honky Tonk Jubilee (2017) The Texan takes on native dance hall music with his 2017 platter of honky-tonk deep covers. Barreling piano and horns scamper through hillbilly soul on Roy Acuff's "Night Train to Memphis." Unexpected highlight "Jamestown Ferry" licks life back into the forgotten country hit, and Hank Williams' "Honky Tonkin'" slides naturally into Crockett's clipped, hiccuped drawl.![]()

![]()

![]()

Lonesome as a Shadow (2018) This year's standout fourth LP of originals finds the Lone Star scarecrow confident in his distinct phrasing and vocals, laying out Delta blues sliced with Louisiana and East Texas soul. "The Sky'd Become Teardrops" delivers a two-minute gem that surprises with a midsong tempo twist, and "Ain't Gotta Worry Child" kicks smooth swaying R&B.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Lil G.L.'s Blue Bonanza (2018) Fifth offering and second helping of covers Bonanza splits between blues shuffles like "Here I Am" and "Bright Lights, Big City," alongside a chunk of Ernest Tubb honky-tonk turns. Takes on Tom T. Hall's "That's How I Got to Memphis" and Danny O'Keefe's "Good Time Charlie's Got the Blues" serve up highlights.![]()

![]()

![]()