The Lone Ranger

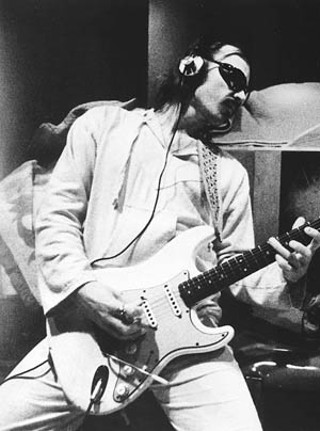

Lone Star songwriter of the spheres, Jerry Lynn Williams

By Bill Bentley, Fri., Jan. 27, 2006

You say you want it and you want it bad

And that you'd sacrifice all you ever had

And that you'd be happy instead of sad

If it just wouldn't take you forever

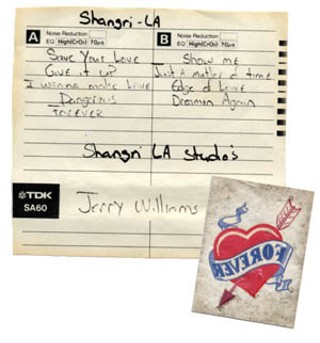

For more than 20 years, I've carried around a TDK SA60 cassette, keeping it in whatever car I drive, and when cars quit coming with cassette decks, I put it on my desk at Warner Bros. Records. It's dated 8/22/84, and at the top of the j-card is written "Shangri-La." There are nine songs on the tape, five on the first side and four on side two.

In so many ways, this tape has become my touchstone, a direct link to a musician who came to symbolize what modern music is capable of. It was recorded by just one person, who played all the instruments and sang the songs he wrote. Sometimes, when not much about the music business makes sense any more, I play the tape and listen to what one man's soul can send out. No matter what the lyrics address, every composition casts a strong spiritual presence.

The last track on side one is called "Forever." It's an anthem to everyone who ever pursued their dreams only to wonder why they took so long to come true. A week before Thanksgiving, I found one of those paper tattoos on the ground in front of my house, the kind you find at the bottom of a box of Cracker Jack. It's a red heart pierced by an arrow, the word "Forever" written across it. I put it inside the cassette case, figuring I'd finally found a cover for these homemade songs. It's a great title for these nine demos, capturing the timelessness at the heart of each one. The man whose name is written across the card spine, Jerry Williams, would have loved it.

Regretfully, I never got a chance to tell him. He died of liver failure three days after I found the tattoo, 57 years old and living as an expatriate on the island of St. Maarten in the Netherland Antilles. His death wasn't unexpected because Williams had been ill for several years, and it almost fit his renegade life and uncompromising character. What isn't right is that so few people have heard Jerry Williams' music of the spheres, or known the magical power of his personality. For that story, it's best to rewind the clock a quarter century and tell the tale of this masked man of rock & roll and how he rode into my life on a white horse with 100 staggering songs.

Would you sell your soul for the money

Would you give it all away

Guess you think it's funny

At least that's what you say

But one of these days now friend

It's gonna come your time

You're gonna get yours

And I'm for sure gonna get mine

Clocking in around 6 feet 6 inches, Williams first appeared before me in person wearing a cape. Little did he know I'd been searching for him for several years. In 1979, an album titled simply Gone appeared, and after reading a review in New Orleans' weekly Figaro, which mentioned "Stax-like horns" on some of the songs, I knew it was something worth seeking. At that time, there weren't many albums with horns, much less ones compared to those from that storied Memphis recording studio. Once I found a copy of Gone, I was addicted. Here was a heart-beating amalgam of rock and soul, but so unique and modern that it was almost impossible to describe. Who was this wild man, and where did he come from? More importantly, why hadn't everyone heard of him already?

Back then, there wasn't really a way to find out. Williams wasn't mentioned in any books I could find, and even his new LP wasn't available any more. Every now and then, a 49-cent used copy showed up in the stores, but after only a few months on the shelves, Gone had gotten goned. It was all a big mystery, so I went looking. The more I listened to his songs, the more obvious it became that true greatness lurked within, and that most likely, an intriguing story went with it.

The door opened a bit in '81 when Delbert McClinton had a Top 10 hit with a song on Gone called "Givin' It Up for Your Love," but in a way that only deepened the mystery. That's why when I found myself backstage at a Leon Russell concert in Los Angeles in 1984, and noticed a tall man in sunglasses standing peacefully alone in a corner, I somehow knew I'd found my guy. It's as if I'd gotten some telepathic message telling me this was the elusive Texan. I approached him.

"Are you Jerry Williams?"

He gave me a huge smile. "Sure am, how can I help you?"

I quickly explained my obsession with his '79 album and said I'd been looking for him for five years.

"Well, you found me," he said happily, and invited me out to Shangri-La, the Band's recording studio in Malibu where he just happened to be living. Thus began a 21-year friendship with one of the most talented Texans to ever make music, not to mention a larger-than-life persona obvious to anyone who ever had the good fortune to spend more than five minutes in his presence. As Delbert McClinton once told me, to be around Williams you "better be well-rested."

Born in Dallas and raised in Fort Worth, Williams started playing professionally when he was barely a teenager, quitting school at 14 to start a band. In 1965 he went to see Little Richard perform, and after the show the rock & roll star offered Williams a place in his group.

"Richard needed another rhythm player," Williams recalled in a 1985 interview, "and when I joined I was the only white guy in the band. I had to lie about my age; I was 16 but said I was 21 because I had the street sense to pull it off. We took off for California on the train. Richard told his lead guitarist to take me in the bathroom with our Strats and teach me the songs.

"We had a little amp in there too and we wailed. The guitarist told me, 'Man, how'd you know those things? You're white. You ain't supposed to be able to do that.' He taught me not to be afraid of the high strings, and also said if I'd teach him how to sing he'd teach me how to play lead. I said that's a deal. He was a monster player then, and when he changed his name from Jimmy James to Jimi Hendrix I knew he was going to be huge."

Eventually the underage Williams got sent home when the authorities discovered how young he was, but that didn't stop him from quickly putting together a 13-piece band called the Top Beats and touring around the Southwest. Married at 17 and soon a father, Williams found himself fronting a band at a local club called the Silver Helmet, run by several Dallas Cowboys.

By the time Gone came out on Warner Bros., Williams had already had a lot of high hopes and dashed dreams to experience. In the Sixties he'd been a member of High Country, which released an album on Atlantic, and upon going solo shortly thereafter, he found a guardian angel in producer David Briggs (soon to find fame working with Neil Young) and his Spindizzy imprint on CBS. The first LP came and went fairly fast, and while there were plenty of deep emotions and blazing style on it, the public never connected with either, no matter that label head Clive Davis had personally promised the singer that CBS would do whatever it took to break the album. As soon as Davis' well-documented troubles with the corporate brass started, a second album began to vaporize and Williams could see the writing on the wall.

"I was too young," he said. "I didn't know how to handle it, and they didn't know how to handle me. I walked out. I knew they were trying to mess with me, and I wasn't going to stand still for it."

From that early promise of his debut solo recording came the first in a series of career nosedives. After the album's appearance in 1971, Williams was back in Texas milking cows to pay the bills. "I milked 90 cows, seven days a week, twice a day. Once at 3am, and once at 3pm," he explained. "But I kept singing, trying to stay in practice."

Following a few more years in limbo and the expiration of his CBS contract, Williams got back in the music game in '75, first performing with Dave Mason in L.A., and then making demos with Leon Russell at the Shelter Records studio in Tulsa. Those demos came to the attention of Warner Bros. Records president Lenny Waronker, and were strong enough to get Williams a new recording contract. For the Gone sessions, heavy hitters were enlisted, including producer Chris Kimsey, fresh from the success of engineering the Rolling Stones' recent Some Girls LP, along with Booker T. & the M.G.s' guitarist Steve Cropper and Wings' drummer Denny Seiwell. Even then, the album belonged completely to Jerry Williams.

"My music's coming from heaven," he told me on my first visit to Shangri-La. "I have so much faith in it I get cold chills. It's hard talking about it, but I know it's the truth. Writing a song is to stir the emotions, and if you touch one soul you touch the whole universe. I believe in it 1 million percent, and the happiness I feel, I want to give to other people."

Unfortunately, that happiness was seriously sidetracked after Gone was released in 1979, but to this day no one has fully explained why. Cropper has mentioned an irreconcilable rift between Williams and Warner Bros., one so serious that it almost broke into open warfare before each side tore the sheet and went their separate ways. There are stories of one of the musician's reps walking into the label's Burbank headquarters with a submachine gun, demanding more promotion muscle be put behind the album. This was immediately followed by a restraining order barring the artist and his management from the building.

Needless to say, no one wants to talk about it now, and for his part, Williams spent the rest of his life trying to heal the wound between himself and Warner Bros. Some of that must have worked, because only a few years after Gone was shelved, Lenny Waronker produced a majestic cover of Williams' "Forever Man" for Eric Clapton, resulting in one of the guitarist's biggest hits of the Eighties and more Williams songs finding their way onto more Clapton albums.

Around this time, the elusive Texan surfaced at a favorite Malibu club called Trancas. It was billed as his debut solo performance, promising Mick Fleetwood on drums and several special guests. A full house showed up, but the special guests never quite materialized, except for the onstage appearance of adult actress Seka, lending her presence as a visual backdrop to the music. Williams tried reaching Fleetwood via a phone patched into the club's PA system, and when he called the drummer's home and surprised him, he got in some good jabs before letting him off the hook for the evening. That night, Williams performed accompanied only by his own piano.

Watching him play, it was obvious he was off in his own world, one ruled by the absolute definition of soul, where one's inner life is expressed entirely by music. Naturally, it was the only advertised Jerry Williams show in Los Angeles for the rest of the Eighties. An attempt to add him to a concert billed as Millions of Williams in '85, featuring Victoria Williams, Lucinda Williams, the Williams Brothers, and MC Marvin Williams got close, until the Texan said he didn't have time to assemble the 15-piece band he'd need to play a set.

The last onstage sighting in California before his move to Oklahoma was during his Fort Worth running buddy Delbert McClinton's set at the Palomino in North Hollywood. Williams took over the piano, and played an original ballad unaccompanied by the band, who all stood there with their mouths open in sheer wonder. There wasn't a sound heard in the raucous room during the entire song, and at the end an experienced pro leaned over and told me, "I never want to hear another song in my life, because no matter what it is, it'll never be that good. I'm done," and then walked out of the club. Williams himself gave the audience a slight nod, and then walked out too. Shortly after, he left the state and bought a big spread in Leonard, Okla., and started writing more songs than ever.

By then, he was becoming the go-to songwriter. Clapton covered five Williams songs on his Journeyman album, including "Pretending" and "Running on Faith." Bonnie Raitt, who had started with Gone's "Talk to Me" on '82's Green Light, included "Real Man" and "I Will Not Be Denied" on Nick of Time, which won three Grammys. Williams contributed five songs to B.B. King's King of Blues, and co-wrote "Tick Tock" with Jimmie and Stevie Ray Vaughan for their Family Style set. The publishing royalties were rolling in, but for Williams, who added his middle name Lynn to minimize confusion with singer Jerry Williams Jr., aka Swamp Dogg, he always kept his eye on the prize of making more albums of his own. Before long, I had a whole wall of new demos, and frequent calls from the singer, testing the waters regarding a return to Warner Bros. He felt the need to mend fences, and truly felt his music could make a difference.

"Music is the voice of angels and spirits, and if you treat it that way, that's what you'll get out of it," he said, and believed it. I'd always refer to him as the Twisted Christian, because he had a true faith in God. At the same time, he wouldn't be denied any of the worldly pleasures.

Finally, after not finding any takers on a new album, Williams decided to do it himself and released The Peacemaker on his own Urge label. Once again, he played most of the instruments himself, though Clapton, Fleetwood, and Stevie Ray Vaughan also contributed to the sessions. It includes his original version of "Running on Faith," along with "Sending Me Angels," later covered by Delbert McClinton and several others. The man the Los Angeles Times recently eulogized as "probably the most successful unknown songwriter in rock and rhythm and blues" had re-entered the ring, though only a select few knew it.

The album never got national distribution, and while Williams did his best to get it heard, not even his hardcore fans ever got a chance to find it. None of which, obviously, slowed the singer down a bit. The last time I saw Williams in person was at the Hole in the Wall in 1994, when he came to town for SXSW, and showed up at the release party for the Texas Tornados' new album 4 Aces.

In a room full of stellar musicians, he was the brightest light there. He had a walkie-talkie to keep in touch with his tour bus driver, never mind that he wasn't on tour, and a cell phone to call his limo driver. Watching him go back and forth from one to the other was like observing a man playing ping-pong with himself, and at last when the Tornados took the stage, Williams slipped out like the Lone Ranger he often seemed to be. If he wasn't going to be making the music himself, what was the point of being there? In his endless grace, it wasn't a slap at anyone else, it was simply the way it was. So off he went.

Once Williams moved to St. Maarten in 2002, I kept staring at the cassette he'd given me in '84. It would stare back at me, daring me to do something with it. Then one day it came to me. These nine songs had been an invisible soundtrack in my life for so many years, surely others should be able to hear their beauty too. I found a small label to take it on, and we titled it Demos From Shangri-La. Williams even had his publisher in England e-mail us a sound file of a new ballad called "Love and Shelter" that was absolutely gorgeous, and the perfect end for the album. After mastering the music, the label got cold feet because there wasn't anyone to sign a contract for the deal, and the label head was afraid one of the old studio owners would come out of the woodwork to claim rights to the original recordings.

The bad news is that the album never came out, but the good news is that instead of my 22-year-old cassette, I now have a supposedly indestructible compact disc to last me the rest of my days. Williams was disappointed, but in our frequent e-mail exchanges he understood the timidities of the music world. After all, he'd been fighting them his whole life, usually without a Tonto by his side for support. He'd sign off each time as "His Jerr-ness King Solomon," and promise that glorious days were ahead for us all, never doubting the wisdom of his Lord, or the unending beauty of the world.

To this his day, too many people have never heard Jerry Williams' music played by him. Very few know what put the magic there, and how a young teenager living in Fort Worth had turned his life over to chasing the sound he heard in his head and in the wind. Sometimes he connected and sometimes he was spinning his wheels, but Jerry Lynn Williams never quit, right up until he took his last breath on November 25, 2005, down in St. Maarten, where he'd gone "offshore," as he liked to say, to get away from what the recording business had become. There, he could write the music he knew could change the world.

"It's gonna be something," he said. "I hope it will, if God will stay with me. And I don't see any reason why He'd abandon me now."

Save your love like it means the world to you

That's exactly what your love means to me

Like a spirit, Lord, finally set free

Save your love for me

In the world of Jerry Williams, there was always hope. He was constantly dreaming of the day his songs would lift the lives of his listeners, taking them to a better place. His last messages to me were not about moving on, but about all the music there was still to be made. When I found out Williams had died, the chorus from "Save Your Love" – the very first song on the demo tape he had given me so many years ago – started playing in my mind, as it often did when I needed a friend. That's when I finally figured out what Williams meant: he was writing from the Lord's viewpoint, telling us that in remembering to love Him, the kingdom of heaven was right here on Earth. And for that, we should all smile for the masked messenger of rock, for we know exactly who he was. ![]()

All lyrics by Jerry Lynn Williams

Bill Bentley has bought over 25 copies of Jerry Williams' Gone for friends, each copy for under $1. He's still trying to get it reissued on CD.