Honky-Tonkers Don't Cry

Coming and going with old country soul Dale Watson

By Darcie Stevens, Fri., Nov. 25, 2005

South Austin's Broken Spoke is splintering. Packed to the low-slung rafters, the mythic honky-tonk is pulsing to the beat of hundreds of shuffling Justins. Every breath imagines sawdust and manure, echoing the dusty days of rural Texas. Papa Spoke James White leans comfortably against the tall PA near the stage, arms crossed, face pinched up proudly. If those rusty speakers suddenly cut out, or everyone went stone deaf, no one would miss a dip. The music in this silent film is almost deafening.

Dale Watson & His Lonestars prod the herd round and round the dance floor, Gene Autrys twirling their Dale Evans, frat boys counting off the two-step under their ball caps, a lesbian couple gliding casually, pin-up girls inked from wrist to collarbone. Austin's many colors have at least one shade in common, and he's standing onstage. This is Dale Watson's crowd.

The Lonestars are old Ford pickups, buzzing cicadas, and dirt roads. Hot summer days spent inside drinking sweet tea and listening to elders' stories or outside playing in the sprinklers. Rhinestones, denim, and leather. Texan drawls become deeper with every one of Watson's smartass jokes. The clock reverses its direction, and every shirt and hat fades to sepia.

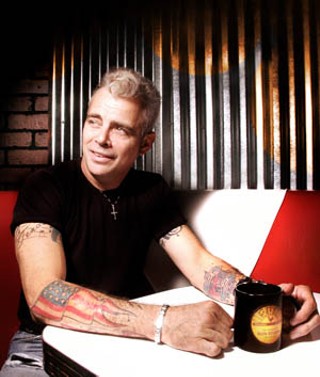

A man like this, a real country star, knows no boundaries in life or in music. Dale Watson is proud without being cocky. Like Merle Haggard, his small frame and classic smile are only a cover for the wheels turning in his head. Country, yes, but far from simple. Steadfast in his ways, true to his meaning, and brilliantly honest, Watson is what country music should be: authentic, legitimate, and bone fide heart.

Which is why he makes his home in Austin, a city outsiders still think of as the home of Texas blues, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and a certain liberal element. But underneath that exterior, like Watson, pumps country blood. Deep in the heart of Texas, many find solace from the music industry. The torch has passed from Bob Wills to Don Walser, and now Watson holds it tight. Not many folks can walk in those boots.

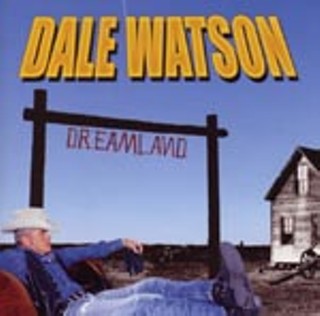

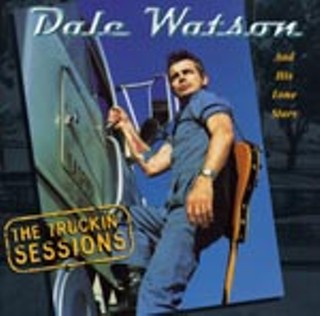

From his first album, 1995's Hightone release Cheatin' Heart Attack, through 1998's country-fried The Truckin' Sessions, 2001's sorrowful Every Song I Write Is for You, and last year's galloping Dreamland, Watson's pen and strum exemplify country. His heart's been broken, his ass whupped, and his Johnny Cash baritone carries the weight of a lifetime. The rest of the country hasn't taken all that much notice – on the other side of the Atlantic, his crowds number thousands – but that's immaterial. Dale Watson saves country music every day and night with one honky-tonk two-step after another, whether folks are listening or not.

If you are, take heed. The man who's obviously "too country for country" is packing up his coin-covered guitar and moving north. He's taking his piano, his awards, his wall-of-fame photos, and hopefully, he's marking all the boxes "return to sender." In six months he hopes to return. Maybe by then we'll have a better appreciation for the special things in life.

Tonight, as Watson hollers Buck Owens from the stage, the sound eases back into the air, every fat bass note, every sad pedal steel, but man, that voice. That voice can mend the deepest heartache. Another Lone Star, please.

It's been 12 years since Dale Watson arrived in Austin. After spending his formative years in Pasadena and playing in his daddy's band, he trekked out to Nashville, then, disgusted, to L.A. Refusing to bend his ways, or rather unable to, Watson found a welcome home in Central Texas, where the people are friendly, the shows ample, and the talent pool bottomless.

While here, his van has experienced the trauma of a million blacktop miles, his Indian motorcycle memorizing the Hill Country. When he wasn't on the road he was in the air, flying to one of many overseas destinations where he's rightly worshipped. Regardless of the hours spent singing, playing, voyaging, the success owed the man never mushroomed on this side of the Atlantic.

He's threatened to quit before, either by implication or directly, which is, of course, the cause of all the ruckus formulated by the announcement on his Web site (www.dalewatson.com) that, "As of January 1, I will be taking at least a six month break." While the streets of Baltimore aren't necessarily the first place country folk think of, it's where Watson's two daughters, 7 and 13, now reside. The man's heading north to be a daddy.

"I'm going to be a fish out of water," Watson admits. "I love this town. I love the folks in it. It's a very unique town. It's going to be a tough separation for me, but I hope it's not going to be a permanent one. This break I'm taking is trying to gear up so I can see some sort of light at the end of the tunnel, musically and artistically, and still be with my family in the meantime. I'm hoping this is only a break, because there are so many things going on."

In four months, hopes are that Zalman King's Watson documentary, Crazy Again, which centers on the singer's hitting bottom following the death of his fiancée Terri Herbert in 2000, will be accepted to the South by Southwest Film Festival with a Broken Spoke gig in tow. That's not to be confused with King's full-length musical for Burnt Orange Productions, Austin Angel. Watson stars as a man who deals with the devil to save his daughter. The film goes into production – after nearly a year and a half of postponements and confusion – late next summer.

There's a book, too: the story of Watson's life, tentatively titled I'd Deal With the Devil after the song Watson penned in the wake of Herbert's death. And don't forget about his upcoming 11th release, titled either Heeah! (because, "No matter how old we are, we always knew some old guy or somebody in our family that always said, 'Heeah!'"), as it is in Europe, or No Help Wanted. That's out in March on Palo Duro Records, preceded a month earlier by a live DVD filmed in Holland. This is what Dale Watson calls "a break."

Watson knows better than most that you never can tell what the future holds. He's held on through tragedy, indifference, and depression, and, at the ripe old age of 43, he's still going strong. In fact, Watson shines brighter now than he ever did as a youth.

"I've never taken that much time off," he laughs. "The most time I went without singing was when I was in the nuthouse for 10 days or a week or whatever that was. I might come back singing like Kelly Willis. Who knows? All this time I might've been a soprano."

That's not what a tour bus full of Europeans has come expecting. Let off at the Continental Club on South Congress, they've planned their entire American tour around seeing Dale Watson & His Lonestars at their long-standing Monday night residency. But that woman up front is no European. Famous groupie Pamela Des Barres takes a break from her book tour to two-step.

The Continental is Dale Watson's third home, apart from Ginny's Little Longhorn Saloon and his quaintly modern condo in North Central Austin, and tonight, three days after the Broken Spoke gig, he's more leather than twang. Here he warbles Presley and Martin along with Bob Wills and Johnny Paycheck. Originals pepper the spontaneous set, blending in perfectly with the Western swing and rockabilly hits. And now for a word from our sponsors.

"Lone Star beer is scientifically proven to eat fat cells," Watson announces. "It's liquid Viagra for both men and women. And the number one reason to drink Lone Star beer ..."

Drum roll, please.

"Chicks dig it!"

Standing on stage in front of the red curtain in his black leather vest and black leather chaps, Watson banters back and forth with the international crowd. He swims through Dreamland's "Fox on the Run," bowing to longtime Lonestars Don Pawlak's master pedal steel and Gene Kurtz's steady bass. But that deep growl is a God-given gift. Nothing touches Watson's voice.

Mixing surf and rock & roll into his traditional country set, Watson gives props to Hag – "He ain't gonna be around forever, a living legend" – and powers through "Mama Tried" like the Okie were grading him. One day we'll all be talking about Watson this way. We'll be saying to our grandchildren, "Sure, 'Drink Up and Be Somebody' is a classic, but have you heard 'Nashville Rash'?"

The foreigners aren't rowdy; maybe they're just in awe. For them, this is perhaps the equivalent of seeing Elvis play Memphis or witnessing Buck himself in Bakersfield. It's strange to watch, all these folks ordering Lone Star like it were a delicacy, taking in every sound, every word, every blink of the cocktail waitress' lashes. Three hours later without a break, Watson finally takes his bow. His faraway family will go home humming "Way Down Texas Way," and they'll finally know its true meaning.

There are nine couples squeezed onto the postage-stamp dance floor at Ginny's Little Longhorn Saloon as Watson sings "Honky Tonkers Don't Cry," a crowd favorite to say the least. Every Thursday and Sunday, Watson & His Lonestars pack into the tiny corner of Ginny's, the proprietors beaming proudly beneath framed photographs of her favorite stars and his British awards and trophies. The bikes line up behind the shotgun hole in the wall, engines revving in anticipation and excitement. Greasers and gearheads mingle with the locals at the bar, cold Lone Stars in hand.

Watson's been playing Ginny's on Sunday afternoons for Chicken Shit Bingo since he first moved to Austin. Now it's habit for everyone to come out and play. Like at the Broken Spoke, the crowd reflects all the faces that Watson has touched. There are cowboy hats and tank tops, boots and sneakers, piercings, dreadlocks, and tattoos out the wazoo. The land where old-school meets new. "Old country" is the real tie that binds.

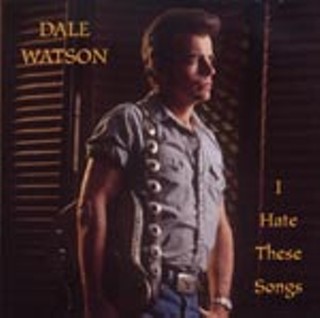

"Whenever somebody says, 'You're playing old country music,' I take it as a compliment," explains Watson. "What they really mean is that it's got roots. I'll play my originals all night long, and they say, 'I like that old country music,' and I think, 'Well, that's interesting. I only wrote that last year.'"

Watson's long-standing feud with Nashville country has been a force behind his music since the start. Aside from the catalyst "Nashville Rash," he played a part in the 1997 documentary Naked Nashville, which documented the corruption behind contemporary country music. "Hot 100" might as well be cuss words to him, and don't even mention Big & Rich.

Earlier this year, Watson went into the studio with famed Sixties producer Aubrey Mayhew and steel guitarist Lloyd Green to record a modern-day Little Darlin' record, a nod to Johnny Paycheck's legendary country music label. Watson set out to prove that new songs recorded with a Sixties mentality can still sound fresh today. "You can still use an old hammer to build a new house," he posits. Unfortunately, after recording wrapped, the Koch Nashville record label tanked, probably thanks to label head Nick Hunter's willingness to push the envelope. Watson's throwback recording might never be heard, but fortunately for us, he takes his influences with him wherever he goes.

"I'm ashamed to be called country music. I'm not saying that I'm Merle Haggard, Johnny Cash, or any of them guys. I just know that they are country. I don't ride horses; I didn't grow up on a farm.

"And it's not so much a blue-collar thing anymore, either. I've had stockbrokers, millionaires, and welders in the audience for our shows. It's nondiscriminatory. It's not just a social music. It's like anybody can like classical music. You don't have to be a billionaire yachtsman to enjoy classical.

"My dream category would be if you hear it, you like it. I wanna be in the if-you-hear-it-you-like-it category."

Sitting on his bar stool beneath the 8-track player, Watson should be in black and white. There's an innocence about him that doubles as rebellion. He's surrounded by friends, and maybe that's what makes him seem so vintage. He's stood up to the man, he's stuck to his guns, and he's been raised up onto a pedestal for it. The dancers swinging in his lap and the band members at his flanks are much more than friends. They're his family. And you always come home to your family.

So while he's sitting at home in Baltimore, learning the ways of the world from his 13-year-old daughter and trying not to think about not playing music, he'll be holding court at Ginny's in spirit. Longtime friend and killer guitarist Redd Volkaert will fill his Sunday slot for the time being, and the Lonestars will bide their time in studio and waiting for the honky-tonker's arrival.

"I don't want people to think that I'm a bitter guy cashing it in, because that ain't what's happening," Watson promises. "I'm just taking this break at the opportune time while this other stuff figures out its time frame. There's lots of stuff going on. These people believe in what I'm doing. I don't want to leave them high and dry. And I wouldn't. At the same token, if everything falls flat, then I'll have to consider a plan B. I'm just taking it one day at a time." ![]()