Riding With Bob

By Lee Nichols, Fri., Aug. 13, 1999

|

|

Calling an Asleep at the Wheel album "A Tribute to Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys" is redundant. For nearly three decades now, that's all band leader Ray Benson and company have been doing -- praying at the altar of the legendary King of Western Swing. Starting in West Virginia, rambling out to California, and then finally arriving at Ground Zero -- Texas -- where they've played every building worthy of the designation "dance hall," Benson and a few dozen different backing musicians have become the undisputed ministers of the country-jazz hybrid with which Wills is synonymous. They are the evangelists, and swing is their message.

But you can't preach without disciples and converts, and Asleep at the Wheel has found plenty. In some cases, conversion was unneccessary; Merle Haggard, Willie Nelson, and Don Walser, among others, knew the gospel long before Benson did. The youth, however, are easily impressionable, ready to be washed in the blood of the lamb, so Benson decided it was time once again to have a big tent revival, and everyone was invited.

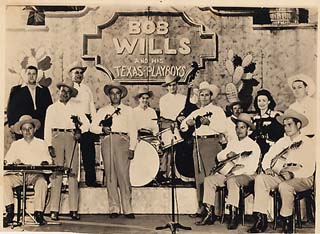

Six years ago, in 1993, the Wheel put out an album that was considered a landmark in the band's already storied history: Tribute to the Music of Bob Wills. It was a star-studded collection that not only won the band a Grammy, it also brought together the old masters -- former Texas Playboys like Eldon Shamblin, Leon Rausch, and Johnny Gimble -- with modern-day Nashville staples like Garth Brooks and Suzy Bogguss, and even an oddball or two, such as Benson's old pal Huey Lewis. And they made it sound great; even the bland, middle-of-the-road types who get blamed for country's current sad state came off sounding like diamonds, and the Wheel reached new audiences that had likely never heard of either them or Wills.

But a mere 18 songs can't possibly encompass all that is a deity like Wills, so the Wheel has done it again. This time, armed with a new contract from Spielberg entertainment juggernaut Dreamworks, Benson has rounded up the suspects -- both usual and unusual -- and put together an album that can both satisfy the purists and reach the masses.

Ride With Bob is the new title, and it's a full tour bus. Walser, Haggard, and Willie are along for the ride, as are veterans Tommy Allsup and Larry Franklin, former Wheel pianist Floyd Domino, fellow country/jazz master Lyle Lovett, top country stars Vince Gill, Steve Wariner, Dwight Yoakam, the Dixie Chicks, Lee Ann Womack, Tracy Byrd, Reba McEntire, Clay Walker, Tim McGraw, Mark Chesnutt, and Clint Black. The Manhattan Transfer make an unexpected appearance, and local Shawn Colvin and Squirrel Nut Zippers round out the revival.

Ray Benson sat down with The Austin Chronicle last month in his South Austin studios and discussed the latest album that surely would have made Bob holler:

Austin Chronicle:In a sense, you've already made this album. Why do it again?

Ray Benson: This is an extension of the same album. [Originally,] I wanted to do a four-album set, but my label at the time, Capitol Records, said, "You're out of your mind. You're not doing a four-album set." So I was lucky to get 18 cuts on the first album. The songs we didn't include on the first album were "San Antonio Rose," "Faded Love," and "Maiden's Prayer" -- the hits. And it was not conscious, because the process is, I'd just go say, "Hey, is there a song you want to sing, a Bob Wills song? I'm doing this thing." And they'd say yeah, or I'd say, "I've got this song that would really fit your voice." Plus, the first album had none of the big band swing stuff. So I really felt like I hadn't finished that record. This is a continuation of that record.

Unfortunately, [Capitol] dropped us, so I couldn't do it on the same label. I also wanted it to be a box set of all of the Capitol Records stuff. But we got dropped, so I took the project elsewhere.

It really is a continuation. Maybe that's a rationalization, but it was never in my mind. My mind was, "Aw, shit, we didn't do 'Faded Love,' aw, shit, we didn't do 'San Antonio Rose,' we didn't do 'Cherokee Maiden,' didn't do 'Maiden's Prayer,' didn't do 'Take Me Back to Tulsa,' which was our first record, our first single in 1973. And the big band stuff -- there was nothing like that on the first album.

AC:It sounds like being a radio deejay and only having an hour to do your show.

|

|

RB: Yeah, cue your songs up ... "Wait a second! I know too much about this subject!" There's also the fine line between commerce and art. Or I don't even want to call it art, but commerce and making this album. That's another problem. Yeah, I wanted to cut 40 tunes, but you can't do that in the commerce world. The world of commerce says no, you cannot do that.

AC:Why do this type of album, with Nashville stars who are pretty different from what you do?

RB: The reason we do this is to bring it to a wider audience. Some people don't like Nashville; I think it's very important. I don't have to preach to the choir. The people who love Bob Wills are going to love it, and Asleep at the Wheel might be the reason they like it, or might have nothing to do with it. But to be able to bring people into the music that don't know anything about it is why [we] do this kind of album.

And this is not a tribute album. I don't like the phrase "tribute album." I did a tribute album in 1993, and it was something we had always talked about as a band: "Wouldn't it be cool if we could do themed tribute albums of all our [heroes]?" You know, we were talking about Fats Domino, George Jones. That was just our thing, we liked to do it. So I did one, and they did one for the Eagles, and then it became a marketing tool. It became labels going, "How can we get ...?" Now it's a blood sport. That was the hardest part of the album -- the lawyers. This is not a tribute album.

AC:How did you hook up with Dreamworks?

RB: They started the label concurrently with their movie company, and about a year later, they hired [famed Nashville producer] James Stroud to head up the Nashville unit of it. I knew him. I was intrigued because of their commitment to interrelation. In other words, if you're in Sony Records, you don't talk to anybody at Sony Pictures, Sony TV. They don't even communicate. At Dreamworks, that's part of the deal: network everybody in the company to do projects. So, I felt like it would be a good thing for this project, because we have a television show and some other things that are yet to be seen. So far, they've been great, because they also have the attitude of, "The artist or the musician does the work and we sell." And so far, they've done that with us. They said, "Go. Here's the money to do what you need to do." The cover and stuff, I said I wanted it to look like a pulp novel, but it could cost a bunch of money to do that. They just said, "Let's go."

AC:Sounds like a Dreamdeal.

RB: Dreamworks, baby! They are really committed to that. They gotta make money; these are not nuns. They're capitalists for sure, but they seem to know that if you don't make something good to sell, it won't sell. That's smart.

AC:How did you fall in love with Western swing in the first place?

RB: I came up in the Fifties and did what everybody did: I played rock & roll, I played bossa nova, I played jazz, I played in the marching band, I played in the high school stage band, the swing band. I played upright bass. And I listened to radio. There was all kinds of radio. I loved music. I played everything.

And then I heard Hank Williams in 1967. I mean, really heard him. We all knew "Your Cheatin' Heart," but my family didn't listen to country music. I heard Hank Williams and went, "Whoa!" It just turned my life around musically. I mean, I was a hippie; everybody was listening to the Grateful Dead and the Rolling Stones, and I listened to all that. I loved all that. But I was a country nut.

On the other side of the coin, I loved jazz. I grew up in an area where jazz was incredible -- outside of Philadelphia. I'd go into Philly and all my cousins were -- and are -- jazz musicians. I grew up with the Brecker Brothers and heavy jazz guys. I saw John Coltrane; I was deeply immersed in jazz.

But as a kid, that was my first group there -- see those four kids? [Points at a black-and-white photo on the wall.] That's me at the top in 1960, and we sang folk music, 'cause folk music was big: Kingston Trio, Woody Guthrie, the Carter Family, the Lamplighters. All these musical influences were kind of going around, and then in 1969, we decided to form a band and get back to the land, which is where all the hippies were going anyway; get out and play country music, half because of Bob Dylan and half because of Hank Williams. But I had all these other musical influences. And I loved the blues. I knew everything. I didn't realize that there was compartments to music, 'cause we listened to all this music and we played it all.

So when we got to do this country band, we said we've gotta narrow our focus down. So we just played hillbilly music. And we said, "Wow! We really want to play roots music." That was our rallying cry: "We're going to play roots music!" I hate Led Zeppelin. Really. I hate white guys sounding like wimpy blues singers. But we loved blues. I love Jimi Hendrix. So we formed the band. We started doing this thing, and then the creative urge to play, to jam, to improvise especially, was there, and I couldn't do it in country music. You did a turnaround or half a chord, you know what I'm saying?

All of the sudden, Western swing entered, and I went, "Wow, I can sing hard songs with country themes and play fiddle breakdowns like I've always played in square dance bands. I mean, you could do it all. I could play swing music, improvise jazz however complex you want within the structure they give you, and wear a cowboy hat. That was the deal. That's how it all happened. We were in West Virginia, and then we moved to California. There were so many Okies, Arkies, and Texans out there that Western swing was real big on the West Coast. We found the remains of that, and then some of the old guys led us down Texas way.

If you listen to Hank Williams, it was at the peak of Bob Wills' influence, and a lot of Hank's stuff has got Western swing kind of stuff in it, especially the guitar playing, which for me was the whole thing. Like the Texas Troubadours; [Ernest Tubb] is a direct outgrowth of Bob Wills, but it was real country. That's where we came from. On a break, the Texas Troubadours would play hot jazz Western swing, and then Ernest Tubb would come up and go, "I'm walking ..." boom-chucka, boom-chucka. Which is where Junior Brown gets his sound.

|

|

But the jazz part, we ate it up. Here were these guys who could play simple, beautiful, wonderful country music and burn like the guys in New York. And the Texas guys were the guys. Texas and Oklahoma. When we started meeting all the old guys, they were all down here in Austin. We met Johnny Gimble and Willie Nelson, and that's who directed us down here. They were in Nashville.

We would go to junk shops and buy 78s, go anywhere, because this stuff wasn't reissued back then hardly. You'd find old albums, old LPs, 10-inch LPs. That's how we got Bob Wills music. It was starting to disappear. There was places in Texas and Oklahoma where there were still Western swing bands, but not classic Western swing bands. You had to go back and find the material. That's where I met [Texas Playboys steel guitarist] Leon McAuliffe and all the Playboys. That's how we learned. You had to do that. And we were very lucky to be around when they were all there and learn firsthand how they did it -- hear the stories, hang out, get drunk. I feel very privileged.

That's why I have this. I really feel like we're carrying a banner. And you know, I'm not from Texas, I'm from Pennsylvania, and this friend of mine from Del Rio that I went to college with said, "You know, in the first few years you were playing, it really pissed me off, 'cause you know, here you were from fucking Pennsylvania and you were reviving our music. And then I finally realized you were doing it better than everybody and I got over it." [Laughs.] I said, "Well, thank you, man, I appreciate that," 'cause I always felt like I'm not George Strait. I don't have the lineage that George Strait has. But on the other hand, I have the perspective George Strait doesn't have, which gave me the ability to look at the music another way.

AC:I personally know what it's like to be a hippie getting into country music in the post-Cosmic Cowboy era, but what was it like back in the Sixties when it wasn't so smooth?

RB: From the redneck side of the fence, we used to have to fight our way out of the bars in West Virginia, literally, until they respected us. And that took a week. [Laughs.] But there were fights all the time -- these were redneck, hillbilly bars. On the other side of the coin, we'd go down into Washington, D.C.; our first gig was with Hot Tuna and Alice Cooper, and the second one was with Poco. And the Poco one was fine. That was like coming home. But with these other bands, they'd be like, "Rock & roooollll!!Rock & roll!" But we never got booed off stage. Commander Cody took the brunt of it. We worked with them. They really got us going. They would open for Alice Cooper. I remember them opening for War, and getting booed off stage -- getting shit thrown at them. We just got a little abuse. The [audience] would just leave.

Because Asleep at the Wheel, they figured, was a rock & roll band. You know, we had long hair and all. Even when we moved to Austin in the Cosmic Cowboy era, Greezy Wheels, B.W. Stevenson, Michael Murphey -- they all played the rock joints, and we did too: the Armadillo, up in Dallas, Mother Blues, Houston, Liberty Hall. But we also played the dance halls. In San Antonio, the Farmer's Daughter, the Skyline Club in Austin, because we were a Western swing band. Plus, we played country music and very much wanted to be in the country venues. So we were the only band that did that. That's one of the reasons we moved to Austin because we could play all those hippie joints and we played every dance hall. Didn't leave Texas for six months after we moved here.

AC:Back to the album. Did you pick all the artists that are on it, or did the label pick any?

RB: They didn't make any suggestions. They just kept going, "Great. Keep going." I said this is what I'm going to do. I said look, I'm going to get my friends and people who want to do this. Some of these people just bugged me and said, "I want to be on the album." And it got to be the same thing [as happened with the first album]. I got to a point and the record company said, "Hey, stop." They had committed to 15 tunes and they let me do 17. That was great.

Some of them I consulted with them on. Clay Walker basically collared me in the airport and said, "Please, please, I want to be on this album." I knew him a little bit. He really wanted to do it. He's from Beaumont, and he really wanted to do it. He genuinely wanted to do it. You know, he's not going to make any money from this. He ain't gonna get famous from this. He's just one of those young Texas country singers that I felt like, okay, this is good. This is something that's good for you.

AC:Were there any other artists that you were working with for the first time?

RB: Yeah, the Squirrel Nut Zippers. I'd never met them. I'd heard their music on MTV, and I said these guys have attitude like we had back in 1970. So I sent them a letter at the Backyard, through a caterer friend of mine, and next day they called back.

AC:What made you pick the Squirrel Nut Zippers? I thought that was a real interesting choice.

RB: This whole "swing revival" is mostly big band stuff and they're not. They're just this wacky, weirdo, kinda funky string band with horns. That's what I wanted. And I knew the song I wanted. Then they surprised me and came up with a song ["Maiden's Prayer"]. It was perfect. They want to sound old. And that's part of what we wanted to do was to sound old. The sound of the 78 was very comforting.

AC:There were some other artists that might seem like strange choices. Why Manhattan Transfer, who sing "Going Away Party" with Willie Nelson?

RB: We did a record with them three years ago. We backed up the Manhattan Transfer on a record called Swing. We did three cuts with them, which were incredible. And then also, one of my favorite records of Bob Wills' music is Patsy Cline doing "Faded Love." It's not Western swing. It's Patsy Cline. I just wanted to show the versatility [of Wills' music], and that's one way. It's like an early Sixties pop record. And then we put Willie Nelson in instead of Johnny Mathis. This is the kind of music Bob loved. His wife told me years ago that Bob used to go put a quarter in jukeboxes just to hear Patsy Cline sing "Faded Love." He just adored it. I just wanted to show the versatility of the music. If Bob Wills was around, he would have just flipped over this record, and I can say that with great confidence, really.

AC:How did you meet them?

|

|

RB: I met Tim Hauser at the Rhythm & Blues Foundation thing one night. I put on this thing every year, the Rhythm & Blues Foundation Pioneer Awards that I'm the chairman of. He was at one and said, "I've always loved your band." And I said, "Hey, you guys are the best, man. You're incredible." And I knew the original Manhattan Transfer guys, way back. We talked, and he said, "Someday I'm going to call you up to do something." And a year later, we hooked up to do the Swing album, which was so cool; it had Stephane Grappelli, and the Rosenberg Quartet. It was #1 for nine weeks on the jazz charts. They're just very legit jazz vocalists. It's my favorite cut, if I have to have one, but there's three that really are.

AC:What are the other two?

RB: The Merle Haggard cut of "St. Louis Blues" and Lee Ann Womack singing "Heart to Heart Talk."

AC:I'm not familiar with her stuff, but she sounded good.

RB: She's incredible. She's from up in Kilgore, around in there -- Tyler. She was on the George Strait tour and that's how I met her.

AC: That's a really different version of "St. Louis Blues."

RB:It's a very different version. It was based on Bob Wills' version. It was the one song that Bob Wills did from his early days to his later days. By that, I mean in his early years he did a lot of Bessie Smith, ragtime, "St. Louis Blues," "St. James Infirmary," that kind of stuff. That's the only jazz tune he did all the way through. It's funny, because "classic" Western swing is [supposedly] three fiddles doing "Faded Love." Uh-uh. It's everything. It's that Dixieland, Emmit Miller. That's what I like about it.

AC:To some people Shawn Colvin, who duets with Lyle Lovett on "Faded Love," also might seem like a strange choice for a Western swing album. Why did you pick her?

RB: In 1976, I think, she moved to Austin with a [Western swing] band called the Dixie Diesels. We helped them out a bunch, and I was very friendly with the guitar player, and Shawn was the girl singer. We were doing real good back then. We'd had our first big hit and they were nobody, so we helped out a little bit, hung out a little bit, and then they broke up. They went home [to Illinois], we didn't hear nothing.

She's just an incredible singer. So I called her and she said, "Yeah, I'll sing 'Faded Love.'" And then I thought, how can I make this a little different? And Lyle's different. He's one of my good friends. This is a guy who I would go anywhere to do anything with. He's been so good to me. He likes what we do. We used to back up Lyle when he didn't have a band. I can't say enough good things about Lyle Lovett. He just kills me.

AC:Tell us about the song selection process. Was it always the guests picking the song, or did you pick some?

RB: What I would do is say, "Hey, I'd like you to sing a Bob Wills song on our next record," and then I'd say, "Is there a song you want to sing?" Like Shawn Colvin said, "Yeah, I want to sing 'Faded Love.'" And if they said, "I don't know," I'd send them a tape of three or five picks. Some of them knew exactly what they wanted to do.

AC:Did you have some of them jockeying for the same song?

RB: It only happened once. It was "Take Me Back to Tulsa." Mark Chesnutt and Clay Walker both wanted to do that, and I convinced Mark to do "Stay All Night," which he really did well.

AC:Where there any artists you asked who were unfamiliar with Bob Wills' stuff?

RB: Yeah. Not unfamiliar with who he was, but like Tim McGraw, he was very honest. He said he knew who he was because of George Strait, and he had never sung any before in his life.

AC:Is this album going to translate into any live stuff?

RB: We're going to do a TV show. We're about halfway there. The Nashville Network gave me a really good budget to do a big two-hour show about the album and Bob Wills.

AC:You met Bob Wills before he died in 1975 didn't you? Worked with him on his last session in 1973, for the album For the Last Time?

RB: No, [I didn't work with him, but] I was there. We helped put together the deal. We were on United Artists Records, and our producer, Tommy Allsup, was the producer of For the Last Time. We took the project to United Artists, and I didn't have anything to do with it except to bring it to the label. Then we went down to Dallas to meet them, and as we walked in, Mr. Wills was being wheeled out in his wheelchair. And he was kind of slumped over, and they said, "Mr. Wills, this is Asleep at the Wheel." And his wife said, "I'm going to take Bob back to the hotel, and we'll be back in tomorrow." And he had a stroke that night, never regained consciousness, and died two years later.

"This is that band that is doing your music," I think is what they said. And then he went and croaked, essentially. [Speculating on Wills' thoughts]: "Oh my god, if they look like that, I'm dead!" [Laughs.]

I didn't think much about that particular day except that it was the only time I ever met Bob, so I didn't get to talk to him or nothing. But then two years later, we were going to play the Longhorn Ballroom in Dallas, which was the old Bob Wills ranch house. Bob Wills built it in 1949, Jack Ruby bought it, etc. We're driving up in 1975 to play a gig there, and normally we would do about 600-900 people. And I get out of the bus and the AP reporter is there and says, "Did you hear Bob Wills died this morning? Are you still going to play your show?" I said, "Of course we're going to play the show. We'll celebrate his music." That night 3,000 people showed up. The next week, I remember thinking, "Whoa. We walk in, he walks out and has a stroke. The day he dies we're playing his ranch house." And we were doing a lot of Bob Wills at that point. At that point, I realized we had been handed the mantle. It was a little too hot to handle for a while. It took me about 10 years to say, okay, this is good.