https://www.austinchronicle.com/music/1999-03-19/521590/

Genius of Love

By Ken Lieck, March 19, 1999, Music

|

|

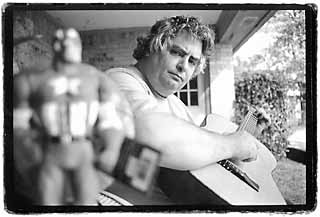

It's February 1999, in the quiet, smokeless confines of the Cactus Cafe on the University of Texas campus, where a rapt crowd looks on as a frazzled Daniel Johnston seats himself at the club's piano. His wavy, almost completely gray mop of hair has grown to shoulder length, and his physical form, not so long ago skinny and youthful, is large and unhealthy looking. The the 38-year-old songsmith looks like some half-mad, aging Mozart overworked to the point of exhaustion from creating some new masterpiece in the service of an impatient monarch.

|

|

Daniel Johnston, you see, is more than a songwriter, more (or, a neophyte might say, less) than a singer. For one, he's also a severe manic depressive, an unpredictable character whose wild mood changes and erratic behavior have become legendary-- triggered sometimes by whatever elements of fame have come his way. His former manager Jeff Tartakov once deemed it necessary to issue a press release begging journalists writing about Johnston to desist from using the dreaded "g-word," knowing the negative effect its use would have on the artist's mental health. Unfortunately, this desperate request was rarely honored. Hence, there have been a number of distressing incidents involving Johnston in his manic state-- usually following the release of a new album or the appearance of a particularly gushing, widely seen barrage of praise in the media-- that have ended tragically with physical harm coming to friends and strangers who had the misfortune of getting too close to him at the wrong time. As a result, Johnston has found himself, as often as not, waking up in whatever mental hospital the authorities found handy.

If his handle on reality can sometimes be somewhat precarious, however, the muse that looks over Daniel Johnston and bestows upon him his many and varied artistic talents is not. Holding an iron grip on him, Johnston's muse has carried the musician through the emotional battlefield that his life has so often been. Just what is that muse? Such things are usually maddeningly elusive, but in this case, the songwriter's inspirations are vexingly palpable. Johnston's music can be beautiful, but more, it is hauntingly, intensely personal, to the point that many find themselves too embarrassed to listen. There is no separating the singer from the song; when you hear the plaintive, childlike voice struggling to hit the notes of "Walking the Cow" (from the cassette the he's best identified with, Hi! How Are You?) singing, "Try and point my finger, but the wind is blowing me around in circles, circles, lucky stars in your eyes," you're right there with him on that lonely dirt road. For those accustomed to the slick sounds of modern pop radio, it's uncomfortable ó a burden having an artist try so earnestly to get close to you.

Daniel Johnston was born in 1961 to William and Mabel Johnston, a devoutly God-fearing, down-to-earth, and fastidiously old-fashioned couple who could never in a million years have guessed what an unusual, gifted, and often downright frustrating package the stork had dropped at their doorstep that fine January morning. While the Johnstons were not what anyone could construe as music haters (Daniel's three sisters and brother are all proficient at the piano, with two of the girls having put in time as music teachers), but the music little Dan was about to begin pouring forth from deep inside his soul was a far, far cry from the hymns and easy listening found in the home of these good, hardworking American taxpayers.

|

|

While the family remained constant, the churches changed more than once, and the family moved from the Mormon-centric state of Utah to wild West Virginia when Daniel was three.

"I remember traveling all the way to West Virginia," says Johnston. "And when we got to West Virginia, I didn't have any friends. When we lived in Utah, there were kids all around-- it was sort of a Mormon community. But when we escaped from Utah up to West Virginia, there were not any kids around that I knew."

Not surprisingly, Johnston's resulting loneliness was the catalyst that propelled the lad into artistic realms, though music was not his first love. "My mom started buying me paper and I started drawing all the time," he says, and the power of the pen was nothing short of magical in its ability to keep the youngster entertained and happy in the absence of a group of friends. Again, however, Johnston's choice of artistic mediums was not necessarily driven by altruistic desires. "I decided early on that there had to be some way to make a living without having to work for it," he laughs.

If the muse charged with spreading the visual arts got to Johnston first, her sister Terpsichore was nipping at her heels all the way. Soon enough, lonely Dan had discovered the family piano. "I used to always play on the piano and pretend I was making the musical score for a monster movie," he recalls with glee. "I could make the piano play itself by jamming on the pedals!"

The atonal thumps produced by Daniel's exuberant cinematic compositions quickly wore on the elder Johnstons, and Daniel was soon given a proper introduction to the instrument. "We had sort of a family tradition where my sister taught me," he explains. "Then my brother taught me to read music, so I was young and I could [already] read music, and towards the end of high school I started playing music by ear, figuring it out, you know, and I started writing Songs of Pain."

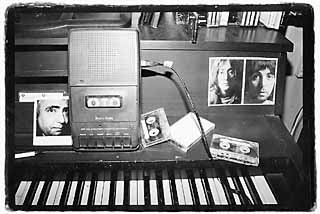

Songs of Pain served as the family's introduction, welcome or not, to the music that would one day inspire countless cries of "genius!" The cassette album, recorded at the family's home via a simple tape recorder set precariously on the Johnstons' piano, bursts to life with the majestic, soaring "Grievances," which Daniel has proudly dubbed his "Song of songs" and to which he has alluded in countless subsequent melodies. Whipping effortlessly between wistful, cheery pop and somber, longing ballads, "Grievances" introduced themes and characters that remain integral to Johnston's oeuvre, most notably that of his boundless love/obsession with a young lady the singer believed he was fated to marry, but who had instead rejected his courtship and wedded the director of the local mortuary. "I saw you there at the funeral. You were standing there like a temple. I said, 'Hi, how are you? Hello.' Then I pulled up a casket and crawled in."

To Johnston's fans the world over, hearing the singer in his now-trademark shaky, childlike voice, setting to music the deepest sorrow of eternally lost love, is a moment of pure, brutal honesty and desire. Just as brutally honest, however, was the elder Johnstons reaction to "Grievances" and the remainder of Songs of Pain.

|

|

"It made a lot of noise!" replies William Johnston when asked what he thought about Daniel's initial recording efforts. Shortly thereafter, the elder Johnston moved the piano into the recreation room in the basement so it wouldn't disturb the rest of the folks in the house "because he was playing it all the time-- and loud!"

As Daniel continued marching forward in the face of adversity, it soon became clear that it was the senior female of the Johnston clan who was to be his harshest critic. Despite the inclusion of cautionary tales decrying premarital sex ("Prematerial Sex"), the evils of marijuana ("Pot-Head"), and the Biblically themed "A Little Story" on Songs of Pain, anxious and often teary admonitions from mother Mabel Johnston not only accompanied each round of new recordings, they actually became a staple of the tapes themselves! Typical motherly screeds of, "You'll never amount to anything!" peppered albums as between-song patter.

|

|

As high school ended and life continued on, there seemed no immediate danger that Johnston's music was going to bring the family any great riches, and so it was that the bird left the nest. Attending art school at Kent State for two and a half years, Johnston then followed his brother to Texas for a long visit. After landing in Houston, where he manned the "River of No Return" ride at Astroworld, Johnston found himself in the famed Live Music Capital of the World by 1985, where his talent in the visual arts was called upon to save him from the dreaded spectre of real work. He attempted to ingratiate himself within the clique of Austin's underground cartoonists, getting as far as showing some of his drawings to the (apparently just visiting) famed creator of the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers, Gilbert Shelton, but having no real luck in getting any work published.

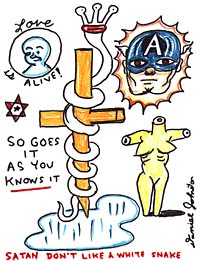

One has to wonder how the cabal of hippie artists reacted to the advances of the shy, strange, devoutly Christian-raised boy from West Virginia; though Johnston has always been fond of comic books, it's largely the symbolism he finds hidden within Captain America and Casper the Friendly Ghost that informs his drawing. Turned away by the "professionals," Johnston returned to the "studio," this time with only a toy chord organ as accompaniment. Meanwhile, he supported himself with jobs at various fast-food franchises. More cassettes issued forth, along with a much-needed dubbing machine; previously, when someone requested a copy of one of his cassettes, Johnston was obliged to throw a blank tape in the recorder and perform the entire album, start to finish.

Eventually, Johnston's unusual blend of charity and self-promotion led to positive results. Among those who had cassettes foisted upon them was Kathy McCarty of the popular and acclaimed local band Glass Eye.

"He gave her a tape," remembers Glass Eye co-founder and Johnston's current producer, Brian Beattie. "And I remember her-- I think she was dating Jon Dee [Graham] back then-- telling me about Jon Dee's reaction, because Jon Dee, as a songwriter, you know, people who are 'songwriters' songwriters' sit in judgment always of other people's songs, and Jon Dee was just ... frightened! Initially, I guess everyone who's heard it for the first time, you're kind of like trying to confront or understand that nervous feeling you get, that voyeuristic feeling from listening to how intimate [it is]."

Johnston soon got a call from the band ("Me calling him up at Tom's Tabooley was like, you know, the President calling you up or something. He was like, 'Oh! Oh! Glass Eye! I can't believe this!'" recalls Beattie), and that was all it took. At their first show together, many of those who witnessed Johnston's shaky solo performance already knew who he was because of his tapes. In fact, word got around so fast, Johnston even ended up on an MTV special about Austin, where he was seen coast to coast and pole to pole waving his homemade cassettes frantically in the air-- cassettes which he no longer had to give away, but was selling instead.

"About a month later," recalls Johnston, "after the MTV show, I stopped playing out. I just started drawing pictures all the time, spending time by myself."

That sounds harmless enough, but unfortunately, this early mood swing was only a small taste of an increasing tendency toward emotional extremes that would adversely affect the musician's career-- and his life. Things were still going well more often than not, however, and when Johnston hooked up with manager Jeff Tartakov, who began duplicating and distributing the singer's tapes, his songs started getting into the hands of more well-known musicians-- eventually to be covered by everyone from Sonic Youth to fIREHOSE to Pearl Jam. Johnston even got the attention of veteran producer/Svengali Kim Fowley, who took him into the studio with a full band (Texas Instruments). The unlikely frontman liked the initial recordings well enough, but balked at the amount of control Fowley demanded.

|

|

In the end, Johnston bought the tapes from Fowley, self-released, like his previous tapes. More popularity followed and more recording. Johnston joined the Butthole Surfers on their compilation, A Texas Trip, and afterwards Homestead Records started putting out several of his cassettes on vinyl (and later, on CD). Unfortunately, every action has an equal and opposite reaction, and in Johnston's case, the reaction to his various successes was an increase in his manic episodes. In the next few years, such events were legion. It was in Austin, actually, after someone introduced him to LSD, that he attacked a friend and landed in a state institution for the first time. Later, in New York, where he had just recorded a version of "Pale Blue Eyes" with the Velvet Underground's Lou Reed and Moe Tucker, Johnston disappeared into the Big Apple and found himself briefly visiting Bellevue.

Soon it seemed that Johnston was spending more time in hospitals than out, and his time inside seemed to be doing more harm than good. First of all, his condition simply required more monitoring than the institution was capable of-- their business was to handle large numbers of people with mental problems the best they could. Rather than seeing his condition improve, visitors in those days only saw a well-sedated Johnston unable to write, draw, or for that matter, talk for any extended period of time. Between incarcerations, Johnston eventually ended up in an apartment on 41st Street (conveniently located only a few blocks from the hospital) and things were once again looking up; he had a girlfriend he'd met in the institution, and Tartakov was working desperately to get him the major label deal he had dreamed of all his life.

The planned deal, with Elektra Records, was not to be. Johnston had grown increasingly erratic, and fired Tartakov. Elektra declined to take on the responsibility of having the singer on their roster without Tartakov coming along to keep an eye on him. "That all fell through because Daniel kinda got off the wagon there for awhile," explains Johnston's father. In 1991, after the senior Johnstons retired and moved to Texas, and it was decided they should be the ones to keep an eye on their troubled son. Having lost his chance at Elektra, Johnston then found himself entering his mid-30s and moving back in with his parents.

One of Johnston's last career advancements before his retreat to the small town of Waller, about a half-hour outside of Houston, was finding a new manager and landing that magical record deal. Atlantic Records took the bait and brought in Butthole Surfer (and pal) Paul Leary to produce 1994's Fun, Johnston's long-awaited major-label debut. The singer was far from in good shape, however, and the album came out with little musical involvement from the artist; aside from some keyboard noodling, the instrumental work was done by others, reflecting Johnston's then-inability to play adequately. Atlantic didn't seem to have much of a clue about what they'd gotten into, or how to promote it. One rather horrid video was made, the price of which came out of Daniel's pocket.

"I never even asked them to come, you know?" says Johnston. "I had $35,000. I was going, 'Yeah! I'm rich!' The next day they came out, made a video, and a couple of weeks later I get a $30,000 bill. Isn't that a ripoff?"

While Johnston's Atlantic A&R man seemed to have a handle on his signing, the label didn't and Fun stiffed. A couple of years passed without Atlantic doing much for Johnston, and while they kept insisting Johnston hadn't been dropped, he was never mentioned on their advertisements, Web sites, anywhere. And he was getting nervous; he knew there was a deadline for him to provide them with new material, but he wasn't hearing anything from them about recording. He was also getting fat. The medication he was taking and the complete lack of anything to do in Waller had turned him into little more than an eating and sleeping machine. Luckily, Brian Beattie, who had been brought in to produce a track by Johnston for the movie Kids (a project with only slight ties to Atlantic) decided to stay on and work with his friend on new material to submit to the label. After a good deal of hemming and hawing, though, Atlantic finally announced that they had no further use of Beattie's-- or Johnston's-- services. That's a decision that didn't bother Beattie in the least.

"When all is said and done, the tape that I made for him essentially cemented that he oughta get dropped," says Beattie, "and that was the best thing ever to happen to me and Daniel as far as doing it together, because we're both listening to it and we're both satisfied and they're unsatisfiable. They just obviously don't understand."

|

|

Portand, Oregon-based indie Tim/Kerr Records, on the other hand, doesn't seem like such a bad idea, according to Beattie.

"Now he can say he's on the same label as Pere Ubu!" laughs Beattie. "And I think that makes a whole lot of sense. I think Daniel could easily be the biggest selling artist on Tim/Kerr Records, which would really give him more attention than he ever could get on Atlantic."

He's ready for it, too, with three albums in the can or nearly there, including a greatest hits collection, which looks to be Johnston "singing all my old songs with saxophones in it"-- something he feels better about with the help of his friend Beattie rather than Kim Fowley. There is a snag, of course; after months of delays, the Tim/Kerr debut is still somewhere in limbo, reportedly due to illness at the top level of the label's minuscule staff. Even though the label hasn't even returned calls to their artist and producer in weeks, both Johnston and Beattie say they're not worried about the situation.

Whenever it appears (and advance orders now number in the thousands), Rejected/Unknown will be worth the wait. With the new album, Beattie has managed to keep the songwriter's visions intact while bringing them into focus for the listener. Using a number of different instruments and players, Johnston and his producer have filled the album with a Sgt. Pepper sense of melodic exploration. Silly horns burst out here, peaceful violins sing across still waters there, a toilet flushes in the distance, voices nag at the listener or offer brief snippets of philosophy between songs-- all complementing the lyrical observations: "Love never comes or goes, feelings never really show. What will become of us? No one really knows" ("Darling Girl"). And yes, he's still singing about his lost Laurie-- and she knows it.

"She calls him once or twice a year," Beattie confides.

Outside the studio, Johnston's physical and emotional health has also improved at a steady rate. The singer credits this largely to an increase in visitors to his lonely Waller island, beginning when a booking agent called him wanting to do a benefit show. Others started showing up not long after. Johnston credits his medication with his improved state.

"I'm on better drugs now," he nods, "feeling a lot better, so it really makes a big difference. I went on a tour, my first ever."

He did, to both New York and California. Recently, he also made his first jaunt overseas-- to Switzerland where he performed at a music festival that he says turned out to be quite an avant-garde affair:

"I was the only one who was playing really straight songs," explains Johnston. "There was a guy playing the saxophone, on some kind of wire, standing on a piece of metal. I swear it was about half an hour and at the end everybody applauded. Then I just went out and played my songs."

|

|

Johnston also just reunited with Half Japanese's Jad Fair, with whom he cut an album a decade ago, for recording and some live appearances, and where he hasn't yet been, his drawings have gone on ahead as ambassador; gallery showings of Johnston's work have been wowing art crowds all over Europe. By his side at each event, there's Johnston's constant companion, his fatigued father, looking like he's getting awfully nostalgic for the days when Daniel did nothing but eat and sleep! Dad's resigned to his fate as caretaker, though.

"I go with him to make sure he minds his 'P's and 'Q's," says the elder Johnston, "because Dan has some bad habits he drops into if I'm not there to take care of that. He's on a lot of medication and cannot tolerate mixing any of that with either alcohol or large amounts of caffeine or sweets."

|

|

And so we find ourselves ourselves back in the Cactus Cafe, February 1999, witnessing the sorry sight of a fatigued and confused-looking Daniel Johnston beginning his set. His voice, on the heels of a recent cancer scare (it turned out to be just hoarseness from a combination chest cold and his heavy smoking habit), is gruff and cracking; the closest approximation of stage patter is his occasional hacking cough. Clearly, his throat has no more than three songs in it, perhaps four.

He begins a song, only to become hopelessly lost halfway through, and mutters a flustered apology as he rifles through the worn notebook to find another. Three songs come and go, then a fourth. He turns toward the general direction of the audience's applause, staring blindly past them as though seeking some distant oasis, well-stocked with soda pop and Snickers bars. He returns to the ivories and begins another song. Then another, and another, and another, a bit more energy returning with each note. By the time he's made the mid-set switch to his beat-up old guitar, he's joking around, making the audience alternately laugh and cry from their perch in the palm of his hand.

From his mini-medley of old favorites and new rib-ticklers to his brilliantly twisted rewrite of Paul McCartney's "Live and Let Die," which culminates in a thunderous warning that "I'm a walking time bomb!," Johnston gives people what they came for and more. One more quick apology for all the (by now forgotten) flubs, an exit to frenzied cheering, and another Daniel Johnston show is done. Outside, two drop-dead gorgeous college girls approach the star and ask with a grin if he'd perchance care for some company.

"Um, sure," he says genially. "You wanna come to Denny's with me and my Dad?"

The look on William Johnston's face makes it clear: It's a long drive home and there'll be no Denny's tonight, nor any other detours. And it's a pretty safe bet that whatever the young ladies had in mind, it probably wouldn't have been wise to mix it with his medication.

Missed opportunities aside, these are not bad days to be Daniel Johnston. He's slowly but surely fulfilling his dreams of becoming a star, is free to share his music with the fans who love him (and whom he loves back), and as far as the elder Johnstons, while they may never truly understand why Daniel writes and sings the kind of songs he does, there's no doubt that the two of them are very proud of their son.

"As far as our life here," William Johnston states wearily, "we live more of Dan's life than we do our own right now. Not by our own choosing, but that's the way it works out."

Copyright © 2024 Austin Chronicle Corporation. All rights reserved.