https://www.austinchronicle.com/music/1999-01-22/521043/

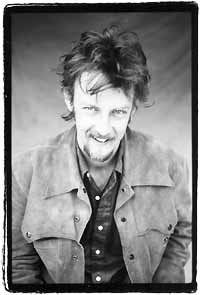

Tasting Defeat

By Andy Langer, January 22, 1999, Music

|

|

"None of this is very interesting to me anymore," says Nelson of his story. "It might be to someone, but I'm a little skeptical. I would like to think that it's the songs that people are interested in. I'm not good-looking. I don't have a great voice. And I'm not a great guitar player. The only thing I can figure out is that the people who dig what I'm doing are interested in the songs. That's obviously what I spend my time working on, not on perfecting my story."

The funny thing about Beaver Nelson's story is that it's actually not all that unique. Every year, major labels sign, record, and drop dozens of bands without ever releasing a single note of their music to the public. Sometimes, as in Nelson's case, it happens twice to the same artist. Nelson isn't exactly the first teenage next-big-thing who's spent time wondering if he's washed up at 26, nor is he the first musician to wait nearly a decade to make an album. What makes Nelson's story of a bad record deal and deflated hopes so compelling is that, whether he wants to admit it or not, the story and the music have now been inextricably intertwined.

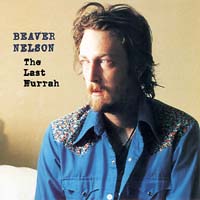

From its title on down to the album's final notes, The Last Hurrah is gritty, soulful, and utterly vital, and it's hard to imagine the album having the same urgency if it hadn't been so long in the making. And once you know what Nelson has been through, somehow the depressing songs sound that much more disheartening and the easygoing songs sound even more surprising. As a matter of fact, Nelson's backstory doesn't detract from the songs and the record as much as it bolsters them.

So, what exactly is the story locals have been speculating about for years? It starts not unlike that of any number of longtime local singer-songwriters -- at the Chicago House. In 1989 and 1990, while Nelson was finishing high school, he would occasionally drive into Austin from his home in Houston for the club's open mike nights, at the invitation of Will T. Massey, one of Nelson's counselors at a Christian youth camp in the Hill Country where Nelson also met his wife. A few years earlier Massey and a few other counselors had changed Nelson's life with a handful of albums. In just four weeks, Nelson was introduced to Bob Dylan, Steve Earle, Lou Reed, Neil Young, Townes Van Zandt, and the Rolling Stones -- all for the very first time.

"I went home, threw away all my records, bought new ones, and started writing songs," Nelson says.

Those inaugural songwriting attempts, which Nelson now calls "awful," led to a pair of homemade cassettes, of which he managed to sell 800 each to his school and camp friends. A year later, in 1990, he graduated high school, went back to the camp as a counselor, and spent the next four months doing cowboy work in San Saba. On weekends, Nelson played open mikes in Waco, San Angelo, and Austin. By the time he moved to Austin in January 1991 for his first and only semester as a University of Texas English major, Scrappy Jud Newcomb and Troy Campell, two Loose Diamonds he'd met at the Chicago House, had already offered him a slot at a regular acoustic showcase they were organizing at Sixth Street's El Chino, where Nelson shared bills and forged long-lasting friendships with locals songwriters of note Kris McKay, Jo Carol Pierce, David Halley, and Robbie Jacks. He also struck up a friendship with guitarist Rich Brotherton.

Before long, the El Chino gig and Nelson's Chicago House open mikes turned into regular gigs opening for McKay, Halley, Jimmy LaFave, Loose Diamonds, and Mike Hall at the Hole in the Wall, as well as the regular Wednesday night host of Chicago House's open mikes. At the time, Nelson didn't realize that not every singer-songwriter that moves to Austin does so well so quickly.

"I just felt like it was supposed to happen that way," Nelson explains. "My whole deal in high school was that I was going to write as many songs as I could because I knew I wasn't real good and needed to learn. And then I got here and was like, 'Okay, my hard work has paid off.' I'm 19 and so-and-so says I'm better than anybody else that's 19; I believed them."

Brotherton and Don Harvey helped feed the local hype when the pair of veterans offered to play in Nelson's band and finance a six-song tape to shop to major labels. For the sessions, recorded at the Austin Rehearsal Complex, Harvey and Brotherton called in A-list backing, including Newcomb, Sarah Brown, Jerry Holmes, Tommy Shannon, Chris Layton, Doyle Bramhall II, Bukka Allen, and Susan Voelz.

"Everything on that six-song cassette was good except my voice," recalls Nelson. "It was awful. I was living on Bukka's floor. The semester was over and I had three weeks before I went off to camp again. I was smoking three and half packs of cigarettes a day, didn't have any money and ate a bag of popcorn, a Baby Ruth, and two Slurpees every day for a month. I was just really ragged and my voice sounded like it."

|

|

"At the time, I hadn't tasted defeat yet," says Nelson. "It hadn't occurred to me that it wasn't going to work. Everything up until than had. A lot of great musicians were gracious enough to let me play with them, and I'd gotten a lot of good advice, did what I was told, and tried to work hard and write as good of songs as I could. I didn't see any reason why it wouldn't work."

Soon after the failed Columbia deal, Nelson's publisher's assistant found him another deal, this time, with another imprint under the Sony umbrella -- a new label called Lightstorm, which had been set up to handle film director James Cameron's soundtracks. The only catch to the deal was that Nelson had to fire his band.

"That was the stipulation," says Nelson. "Period. They wanted me to find musicians my age. The whole scene was 10-12 years older than me. Everyone in my band was at least 30 and these were not people that get fired regularly. And that was the weird thing. I didn't do it because they couldn't play, but because they all looked like my older brother. There were a lot of pissed-off people."

Nelson eventually found bassist Tony Scalzo and a drummer in Los Angeles and recruited Paul Minor for guitar duties. Joey Shuffield, who eventually joined Scalzo in Fastball, replaced the Los Angeles drummer and signed on just in time for a month of Austin pre-production and a Memphis recording session. Like the Columbia deal, this one was ill-fated too. Apparently, Lightstorm was looking for Nelson to make a singer-songwriter-driven grunge album, though Nelson wasn't necessarily opposed to the idea.

"I wanted to rock," Nelson says. "It was fun, but not the record I needed to make. I should have had less fun and not made that record. I don't now how to put it any better."

While rocking was fun, and his new band was young enough, loud enough, and more than capable of recording the album Lightstorm wanted, Nelson says a lot of the pre-production and actual recording was painful because he didn't know how to use his new band effectively.

"I was immediately lost musically because I didn't speak the language," says Nelson. "You have to remember, I was a singer-songwriter who moved here having never played in a band before and was instantly playing with great musicians. I didn't know anything, let alone how to tell the drummer to do this or that. I couldn't speak to them on that level. With Jud and the guys, I'd walk in play a song one time, take a leak, get a Coke, and come back to run through it. That was it. And it's not like I would walk in that first time and say this is what I want to do with this. They were directing the music. Period. This was completely different."

After a month of mixing and vocal overdubs in Los Angeles, where the budget finally soared past the $100,000 mark, Nelson returned to Austin and fired the band.

"I knew it wasn't going to happen," says Nelson. "I could just tell. I wasn't happy making that record, and kept trying to talk myself into being happy with it. But it was all forced and it was nobody's fault but mine. There were some good songs and great playing, but I would have preferred to make the record I wanted with the band I had a better musical rapport with on a $5,000 budget."

Nelson would have to wait to make that album, because although Lightstorm rejected what he'd just recorded for them, the label tied him up for another six months with a clause that gave them the rights to find a different major-label distributor (they didn't). In the meantime, Nelson played around town with a new band and found yet another different band to start a three-month tour with, ostensibly in support of an album he knew would never come out. Worse still, Nelson's Austin fan base had grown significantly smaller. Between all the fired bands and loud, sloppy shows, locals felt like the golden boy had lost a lot of his shine.

"The one mistake, the one regret I have over any of this stuff, is something I didn't do. I should have kept playing acoustic shows in town," asserts Nelson. "I got a little outside myself in the writing during that period because I had this big, loud, and crazy rock & roll band. When I was 17, I was trying to write songs like a 40-year-old and when I was 23, I was trying to write songs like a 17-year old.

"And during that period, I never sat down with a guitar and played my songs for an audience. You can be a little less honest in your writing when you know damn well that nobody in the room can understand a word you're saying. I should have been at the Cactus."

Nelson's return to solo performances came two years and two as-yet-unreleased recordings later, after Nelson returned from Townes Van Zandt's funeral in Nashville in January 1997.

"It just kind of hit me," Nelson says. "I wanted to concentrate on songwriting again. And I couldn't deal with people right then anyway. I just didn't have the energy for it."

Today, Nelson admits part of that post-Lightstorm depression came from how quickly he bought his early hype and how slowly things actually developed.

"If somebody would have told me seven years ago what would happen and then tell me I was going to start making records again at the age of 27, I would have said. 'Okay, I can live with that.' But I was damaged goods for so long that I didn't know if anybody was ever going to want to do anything again.

"And the weirdest part was not understanding why. I could understand why people didn't like this band or that band or didn't know about the direction. I could understand how I pissed some people off. What I never could understand was how, if I was this great songwriter at the age of 19, at what point did I turn into a bad songwriter? At what point was I just not good anymore? That's what I could never understand. It was so confusing."

At the end of 1997, Nelson says he started feeling good again and decided to return to full-band gigs again. Negotiations with Freedom Records proprietor Matt Eskey about finally releasing an album followed, and the pair struck a deal. Initially, the two agreed to release a 14-song, mostly acoustic album Nelson had recorded a year earlier. Although it would have been cheap and easy to release those sessions, Nelson and Newcomb eventually encouraged Eskey to fund a new album, the local indie label's most expensive recording venture yet.

At the end of 1997, Nelson says he started feeling good again and decided to return to full-band gigs again. Negotiations with Freedom Records proprietor Matt Eskey about finally releasing an album followed, and the pair struck a deal. Initially, the two agreed to release a 14-song, mostly acoustic album Nelson had recorded a year earlier. Although it would have been cheap and easy to release those sessions, Nelson and Newcomb eventually encouraged Eskey to fund a new album, the local indie label's most expensive recording venture yet.

"It wasn't expensive by most people's standards, but Matt can't afford to make mistakes," explains Nelson. "It's one of the great things about being on that label. His ass is on the line every bit as much as mine, and because of that, he doesn't overextend himself. I'm not competing with 250 acts like I would have been at Sony."

Even at Sony, The Last Hurrah might have been a standout. Produced by Newcomb, the album includes performances by many of Nelson's original bandmates, including Reiff, Brotherton, Brain Zoric, Kevin Carroll, and Mark Patterson, as well as guest appearances from Champ Hood and Jules Shear. And even with all those different performers, The Last Hurrah is thoroughly cohesive thanks to Nelson's songwriting and singing being consistently compelling and interesting. Looking back, Nelson says the Lightstorm album's failure was definitely a blessing in disguise. Had it, or any number of Nelson's other unreleased efforts, hit shelves, The Last Hurrah might not have been the definitive, well-crafted debut it is.

"We made this record and we made it right," says Nelson proudly. "It's the record I wanted to make for a long time, but didn't know how. Also, I wanted to make it very clear that I still don't take any credit for how this record sounds. It's the guys that played on it and Jud. They knew what I wanted to do better than maybe I did."

With an album finally in stores, a collection of positive reviews, and favorable reports from the AAA and Americana radio fronts, Nelson still isn't sure what to do.

"In the past, I've always known the best and worst scenarios going in. This time, I don't know the best case scenario. I know that there's kind of a minimum thing I'm shooting for. I would like to think that at the end of the day, at some point and at the very least, I'd be perfectly happy if it topped out at me getting in the car and playing gigs at the Cactus Cafes of the world for 200 nights a year. I'd be fine with that. If there's more than that out there for me, that's great."

Of course, the greatest irony of Nelson's story is that The Last Hurrah is anything but that. It's his debut record, after all, and for all his misadventures and false starts, Nelson is still just 27 years old. He may be scarred and a little worse for wear, but he didn't truly grow old waiting for his record to come out.

"Yeah, I know I'm a young guy and have all the time in the world," says Nelson of the last line to a story he didn't want to tell anyway. "But I think having all the time in the world can be as dangerous as knowing your clock is running out. So I got all that time? Now it's, 'What am I gonna do with it?'"

Copyright © 2024 Austin Chronicle Corporation. All rights reserved.