22 to Think About

AMOA shows new Austin art that engages the mind

By Rachel Koper, Fri., Aug. 26, 2005

How does the individual relate to a broader American culture? Exactly how many images of Paris Hilton is one expected to digest in a lifetime? Does getting your culture spoon-fed to you make it taste better? The Austin Museum of Art exhibition "New Art in Austin: 22 to Watch" breaks down some excellent social questions, with local artists challenging themselves and the viewers of their work to access things like urban planning, control over the environment, social distance, and the vastness of known science. The triennial "New Art in Austin" show was created by AMOA Director Dana Friis-Hansen in 2002 to highlight the achievements of Central Texas artists (and the area boasts a lot of both artists and achievements). The curatorial team for the 2005 show – Friis-Hansen; AMOA adjunct curator James Housefield; AMOA director of exhibitions and education Eva Buttacavoli; Joan Davidow, director of the Dallas Center for Contemporary Art; and Clint Willour, curator of the Galveston Arts Center – have proven themselves to be sophisticated and in some subtle ways egalitarian ... very Austin. Their exhibit is quite heavy in theory, both art historical and social. The artists included are idea people, and the issues they communicate are almost all interesting.

This is a show that makes demands on you from the moment you enter the gallery. The floor-to-ceiling triptych by Barna Kantor consists of simple, thin metal panels made of a common industrial material and very low tech. But because there are two perforated layers, the panels come alive as you move around them. Turn your head, and the round shapes of light stretch and fly around the black surface. The scale of the piece puts the shapes above and around you like abstract angels activated by the real-time effort of your brain to make two eyes see one thing. It's a fun double-shutter piece that puts you nicely in the moment. It's as spiritual as you want to make it.

Harder to build but equally open to a spiritual interpretation is Jerry Chamkis' Kosmophone, which is based on gamma rays. An ultraviolet pulse is detected and turned into an electrical current, which is then processed through a MIDI synthesizer and made into sounds. While the tones and settings of a synthesizer are common, what is uncommon here is the source of the sounds and the fact that it occurs in real time. Gamma rays are big. So big that for countless generations humans didn't know they existed. So big that they pass right through the earth like it's nothing. Considered in this context, humans seem small, like godforsaken ants. With some patience and some imagination, you can be humbled by this sensation. Take a moment and listen to the invisible rays passing through you and everyone on Earth. Who knows what you'll imagine? Perhaps a rare feeling of unity.

The flip side of unity is distance and isolation, which are interpreted and brought to the fore in Young-Min Kang's Reconstruction. Kang has taken photos of Texas' world-class highway system, pixelated the images, stretched and warped them, shredded them, then woven the dozens of thin colored strips through a 3-D metal framework. His large, mostly paper installation fills the room ceiling to floor with lots of color. He calls it "my matrix." To this site-specific installation, he has added people: almost life-size figures walking away from you, their backs turned; a couple climbing on their motorcycle and driving away from you. Kang portrays people he doesn't know, who will never meet, who will not enter the museum; they are anonymous urban dwellers.

Sterling Allen uses the anonymity of city life as a source of inspiration. A former employee of a franchise business that cheaply and efficiently processes the public's photos, Allen effectively acts out an urban myth, that of the photo lab clerk who steals a look at – or just plain steals – our personal, private images. He has commandeered photos found on the job (a nonartistic self-portrait, the humiliation of a drunken close friend, a moment of intimacy, an image that's just ineptly taken), enlarged them, and drawn them in beautiful, confident contour lines. They are absolutely hysterically funny. The awkward compositions portray these nameless folks sympathetically, and yet they promote a larger paranoia.

One recurring motif of the show is control of the urban environment. This is most literally portrayed in The Architect's Desk, by Peat Duggins. He presents a cardboard desk wired into a cardboard light table, coffee maker, and lights. On the desk sits a highly detailed architectural drawing for a new subdivision. Many aspects of city living are portrayed: water treatment, a dump, a public park, security departments, roads, and lots for homes with privacy fences. On the wall nearby are several more drawings in the style of a "presentation glossy," like he's pitching the development to ol' Mayor Watson. The drawings themselves are beautifully rendered and on close inspection reveal references to American Indians and an airborne military security team. The work asks each of us to sit at this desk and pretend for a moment that we are in control of our cities, that we are the party that planned things to be the way they are. It asks viewers to accept responsibility. Just imagine that we designed our culture for better or worse – the ghettos, schools, and the military, not just the good parts. I find it to be something of a call to arms, not with God as the architect, but you.

Also grappling with urban planning is Heather Johnson. The former resident of San Francisco has made a spidery installation based on old architectural drawings of the streets she discovered. Fascinated with them as art objects, Johnson carefully embroidered the drawings to scale with various black and gray threads on light gauzy white fabric, going so far as to include the signature of the original artist. Like Duggins' work, it is a fake, but one that asks us to revisit and possibly reflect on the basic infrastructure of our cities. In addition to the "historical drawings," Johnson's installation breaks out into a sprawling thread sculpture, with nails placed on the walls – all the way up, higher than the track lighting – and connected with white threads. To install these intersections, actual blown-up maps were placed on the walls and later removed. It's lovingly tedious, and its expansiveness speaks to our cultural appetite for endless sidewalks and sprawl. Perhaps metaphorically the artist is the creator, the spider weaving its complex web.

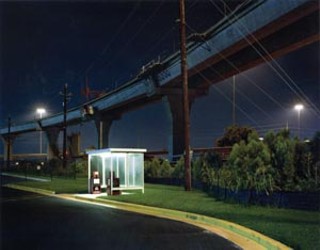

Several artists examine the urban environments as we have created them, using modern industrial elements to represent the future of the American landscape. Michael Osborne's series of large color digital prints depict moody images of our concrete jungle that are haunting. I found the details in the dark shadows intriguing, and I was able to spend more time considering the beauty of Texas overpasses. The panel by the Sodalitas trio – Shea Little, Joseph Phillips, and Jana Swec – echoes this appreciation of and love for the city. They use printing, collage, and encaustic to portray cool-looking buildings and radio towers that radiate waves and circle forms that happily bounce around the panels. In his mezzo-tinted prints, Jeffrey Dell spices up the life of timelessly elegant architectural backgrounds by adding the ultimate city dweller, the pigeon. These birds energize the courtyards. They socialize the gray concrete forms.

Do we control our environment or does it control us? Artist Zack Booth Simpson creates an atmosphere that physically changes depending on the viewer's actions. A self-taught artist and video game programmer, Simpson takes delight in treating the audience as a variable in his game theory. On careful study, like an anthropologist but with math skills, Simpson predicts behavioral outcomes. A rocky-bottomed pool of water is projected on the floor. When you step into this virtual pond, gentle ripples appear on the water's surface. This charming reaction leads you further into the piece. If you stand still, dragonflies buzz up to your place in increasing numbers and gently follow the contours of your shadow. Walk slowly, and colorful algae flowers bloom under your feet. It's a hopelessly lovely effect, for kids of all ages. But if you chase these virtual creatures or move quickly, they all run away. There is a visual experiential reward for calm behavior. Can artists really modify behavior? This aspect of the piece is what takes it beyond the realm of the techie and into the realm of a cultural critique, real social knowledge, and great art.

Ledia Carroll takes a more direct form of control over the environment, asking AMOA: Can I play in your fountain? Can I reroute your water supply? The history of artists dealing with earthworks in Texas is a proud one. Caroll fearlessly puts on those big shoes and pierces the large tempered plate glass windows of the building to allow clear pipes to carry water from the outdoor fountain into and back out of the building. I only wish it had a couple of ping-pong balls to emphasize the directional activities within the pipes.

The Austin Museum of Art will host a series of panels throughout the next couple of months (see sidebar). These smarty-pants artists will meet new audiences both in Austin and later on when the work travels to the Dallas Center for Contemporary Art and Galveston Art Center. I think it demonstrates a maturation of the local visual art scene, the depth and complexity of which stands tall in any urban center. These artists, like the reversed signage on the front door of the museum installed by Jason Singleton, beg for your time and your mind. Are you reading the letters? Are you paying attention? ![]()

"New Art in Austin: 22 to Watch" runs through Oct. 30 at the Austin Museum of Art, 823 Congress. For more information, call 495-9224 or visit www.amoa.org.