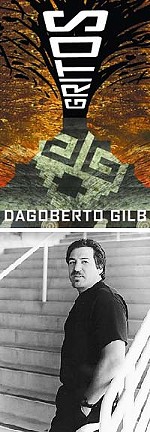

The Years With Carlos Fuentes

The Author Revisits Mexico's -- And His Own -- Past

By David Garza, Fri., Nov. 24, 2000

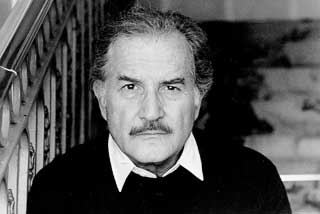

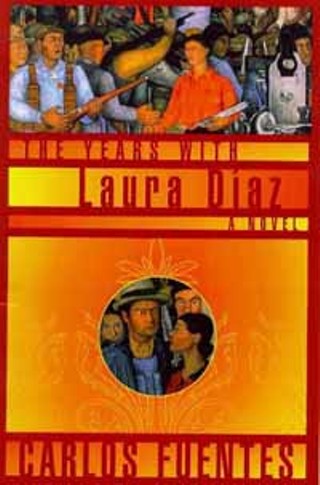

Writers like Carlos Fuentes tend not to exist anymore. His vast body of work not only reflects the historical events and personal lives that shaped Mexico during the past century, it fully serves to create and re-create the social reality of the country. Just as Fuentes cannot imagine a world without Shakespeare and Cervantes, it is impossible to imagine a Mexico without Fuentes. Along with other Latin American masters of the past century, from Borges and García Márquez to Neruda and Paz, Fuentes represents a type of artist that is fading into extinction -- the literary statesman. With his irrepressible political nature and his vast knowledge of history and human nature, Fuentes the novelist is as qualified as any Mexican to serve as the president of his country. With his new novel, The Years With Laura Díaz (Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 544 pp., $26), Fuentes revisits the historical figures and events that created the 20th century, not just in his country of Mexico, but in the world beyond his own borders.

![]()

Austin Chronicle: In your new novel, you have this line which states "art does not reflect reality, it establishes it." In your view, what sort of historical truth does this novel establish?

Carlos Fuentes: You're asking me two different questions, at least. Let me start with the last question. One is that history is an unending process. And if you consign the past to the past only, you are consigning it to a museum. One of the great functions of the novel has been to make the past a living present. To give history the dimension that history books lack. I can read all the history books I want about Russia in the 19th century, yet I will not understand Russia in the 19th century if I do not read Gogol and Dostoevsky and Tolstoy and Turgenev, for example. So there is that dimension of maintaining history alive.

Then the relation with reality -- reality is sufficient unto itself. There it is! It doesn't ask writers to come and write about it. What a writer does is to create another reality, to add to reality. Not merely to reflect reality, but to add something to reality that is not there. Hamlet was not there if Shakespeare had not written him. Don Quixote would not be there if Cervantes had not written him. And we can not imagine a world without Hamlet or Don Quixote. Yet they were not in reality. If the writers had not come around and written them, well, no Hamlet and no Don Quixote. So this is an addition to reality, it enriches reality, it creates a new or further reality, if you prefer.

AC: How can you articulate what this particular novel brings to the common notion of Mexican history that wasn't there before, then?

CF: This was very clear in my mind because I had written a novel about the same period of Mexican history, The Death of Artemio Cruz, which has very much to do with the male protagonist and the events in which the male was central to Mexico in the revolution and the post-revolutionary period. Since I was very young -- a teen, or maybe even a child -- hearing the stories of my grandmothers, who were courageous women, both of them, I said, "I have to write the other side of the story, the story that is not being written, the story seen from the woman's point of view," and this is how Laura Diaz came into being. I knew all these anecdotes -- my great-grandmother's fingers being chopped off with a machete by a bandito and all that, but I had to wait and say the story isn't over yet, so I had to achieve a perspective. I only achieved it well five years ago when I began writing the novel and there you are, it's another vision of Mexican reality, the other side of the coin, if you wish.

To be a woman in Mexico and in the Hispanic world, and perhaps throughout the world, not excluding the United States, is a very uphill fight. I was driven by this because I had two young grandmothers who lost their husbands early, became young widows, and had to fight a lot, one as an educator, the other running a boarding house. And they had to fight to raise their children and were very strong characters. And most of the generational stories in this book come from my grandmothers.

AC: Let me ask you, as a novelist, how you go about re-creating a historical setting that in truth is unattainable. What kind of imagination does that take on the part of the author?

CF: It takes precisely that -- imagination. I didn't have to consult any book at all to write this novel. It was all in my head. Even the events in Europe, the Holocaust, the Spanish Civil War. These were all events that were all in my head. But of course, you are using the imagination and the imagination is a kind of constant relationship between memory and the senses and the opening of the discourse. Not letting the discourse die down. Basically, it is a work of the imagination but based very much on facts that I did not have to consult in history books because they were part of my biography. They were part of my experience.

AC: Where did you do your writing for this novel?

CF: Listen, I live a dual life. I live parts of the year in London. That is where I get up at six, start writing at seven, and write five solid hours and read three solid hours and have no interruptions and get my work done. Then I go to Mexico. Mexico is an impossible place to write. I have too many friends, I have too many people calling on me, interviewing, faxes coming in and phone calls, and the hours are abominable, lunches last until six in the afternoon and the dinners begin at 11 and end at two in the morning! So not much writing gets done, but it's my country, it's my friends, so I just go there and take a big bath of Mexicanness. Then I go back to London, a city where you write beautifully, amongst other things, because you look out of the window, you look at the climate, you look at the rain, and you say, "Hey -- I'll stay and write." Then, the food is not that good, and the English are cold fish, so it's a beautiful place for writing. I recommend it highly.

AC: I want to go to another quote pulled from your book, when you write that "It isn't the past that dies with each of us, the future dies as well." It appears, as a reader, that with every generation, another possible version of Mexico, for instance, dies whether it was the industrial one of Rivera or the neo-liberal one of Salinas.

CF: I think that happens in all societies, if you look at the West from the Renaissance until today. You have all the changes, what Alvin Tofler calls the 'first wave,' the 'second wave,' now the third technological wave. I was recently in Ireland, which is a Joycean place you have to visit. Beautiful country, my God! This is a country that has gone from being an agrarian country with millions of people migrating out of it to a third-wave technological and service-oriented industry. Now it's demanding workers to come in. So history changes all the time, and Mexico has gone through many, many changes -- the revolution brought great changes because it distributed land to the peasants, because it freed the peasants from the hacienda and permitted him to become cheap labor for industrialization, because oil was nationalized, because an infrastructure -- highways, electricity, etc. -- was created. But now this industrial phase is dying all over the world. Now we're going to technology, information, services -- another kind of economy. That again poses a problem for Mexico and all the Latin American countries. Are we going to be left behind in this third wave, or are we going to be able to catch up?

Well, my novel doesn't go that far because it ends in the 1970s when the whole dream of an industrialized Mexico that Rivera had painted with glorious Marxist optimism in Detroit at the service of Henry Ford, who shared this extraordinary optimism that we lived in the best of all possible worlds. Well, Hitler and Stalin and the Holocaust and the Second World War took care of that.

AC: You use Detroit as an epitaph for the "terrible twentieth century." What legacy is left after that century for Latin America?

CF: It is a paradoxical century because I think there is no century that represented greater leaps forward in science, technology, the resources to make life better. But also, there is no more immoral century than the 20th century. By this I mean that having all these great resources to make life richer and better and healthier for millions of men and women, we got the political debacle, the political derangement of the Holocaust and the gulag and mass extermination, genocide. It is difficult to reconcile the scientific and technological advancements with the moral and political horror of the 20th century.

AC: As the 20th century has just closed, is there any way to have a sense of where Mexican literature and art proceeds from here?

CF: I think there is a very clear sense that we have attained an identity. There's a very strong Mexican identity. That's why I'm never afraid of all the people who cry, "Wolf!" when they say that the influence of the United States is taking over. This is superficial. I've always said, "Who's afraid of Mickey Mouse? Not me." So the Mexican culture has a very important profile. I think the presence of Mexican culture in the United States is just as important -- maybe even more important than -- the presence of U.S. culture in Mexico, which is quite superficial. But this poses a problem for Mexico and for Brazil and Argentina and Chile, that we have attained after 200 years of independence, a sense of our identity. Now we have to go toward diversity. Identity first, okay. Now diversity. Respect for religious, sexual, political diversity. This is going to be our challenge.

AC: Very interesting. And since we're talking about the Americas, I want to ask you what is the view of the United States now in the eyes of Mexicans? As so many Mexicans re-enter the geographical space that used to be Mexican territory, especially.

CF: You know curiously, I was having breakfast recently with Arthur Schlesinger, who wrote this beautiful book Alive in the Twentieth Century. We were commenting on how the anti-American sentiment has gone down in Latin America. It is due to the fact that a lot of us, writers of the first rank, have been saying, "Hey, let's stop blaming the past. Let's stop blaming the Spanish conquest or the gringo influence." Let us try to solve our problems here and see that we are responsible for our own destiny. There may be all the foreign pressures, but basically we have to solve the problems right here in the village, in the barrio, etc. As to the Latino influence in the United States, I think it's welcome. I simply think it means that we are going to live in a multicultural society. All of us in the next century. The United States is no longer a WASP country. It is also a Latino country, and it is an Asian country, and it is an Indian country, and it is a black country. It's a rainbow country, and it's a multicultural country.

AC: Do you think that this relationship between Mexicans and Mexican-Americans has changed in that it's become closer, more understanding of each other?

CF: I think so. There's still talk about the distance. There's always the problem of a new generation, you know, a new wave of immigrants comes in and the older wave is menaced in a way. But at the same time, this older wave is achieving status and an identity that is not divorced from their Latin roots. I mean when the lieutenant governor of California, Cruz Bustamante, is the first Chicano politician to reach that level, President Zedillo of Mexico went to Sacramento, and he spoke in Spanish. Gray Davis spoke in Spanish. Cruz Bustamante spoke in Spanish. So the culture is there, and it's accepted. And even George Bush and Al Gore speak Spanish suddenly! The prejudice that existed against Hispanics, against the Spanish language, I felt very much as a child. Listen, I went to Texas as a little boy, going to Mexico every summer and I read signs saying, "No dogs or Mexicans allowed" in restaurants. So there is a big change. There is a big change.

AC: Let me ask you, since you mentioned George Bush and Al Gore, it's very trendy these days for politicians to spout off a few words in Spanish. It's fine to do that sort of thing, but what are they really doing for Mexico or Mexican-Americans or Latinos in general? What do you think really needs to be done between the governments of Mexico and the U.S.?

CF: Well, we have outstanding problems between Mexico and the United States. One is trade. Okay, very good, I'm all in favor of the flow of trade and investments -- of productive investments, not speculative investments -- but I wonder when we're going to have the same attitude toward the movement of peoples. Why do things travel freely and people do not? So free trade cannot be disassociated from migrant labor. Right now the U.S. has the lowest unemployment of the past 50 years. They can no longer say that Mexican migrants take labor away from American workers. That simply is not true. Mexican workers add to the wealth of the United States, they do not subtract from it. Maybe it will be a good time now with Fox coming in, and who knows who your next president will be, then we might be able to find some sort of arrangement by which the status of the migrant worker from Mexico into the United States is protected, even quantified according to needs, but is not demonized. It doesn't swing according to whether your economy goes up when the workers are welcome, or if the economy goes down, the workers are beaten and thrown out and sometimes even killed. Then we have the problem of drugs and drug certification, which is a hypocritical exercise by which the U.S. Congress, in a holier-than-thou attitude, certifies or decertifies Mexico and Columbia. But who certifies or decertifies the country that demands the drugs, which is the United States? So there we have areas of disputes, which I think we can solve in a peaceful manner.

AC: Let me ask you -- if you visualize Mexican history as a continuous mural, what is your opinion of the current president-elect, Vicente Fox? What sort of Mexico does he represent?

CF: It's a historical event that after 71 years, the PRI is out. And I think that people voted against the PRI, and Fox represented the anti-PRI vote, so there he is. He's elected now, but it is one thing to win an election and it is another thing to govern a country as difficult as Mexico with all the problems that are left over. Fox will have his honeymoon as all new presidents do, but then there comes a moment when we'll say, "Are you solving these problems?" They are very deep problems, sometimes they are century-old problems. Let's see how he does. I think that all Mexicans wish him well.

AC: Getting back to the novel. There are three sisters: Hilda the pianist, Virginia the poet, and Leticia the domestic. One thing that struck me is the way that Hilda and Virginia dream about a Germany that they'll never reach. It seems to hint at a historical tendency in Mexico and Mexican art to either idealize the European aesthetic or to do the opposite and rebel by exploring the indigenous roots. Either way, the definition of the self comes vis-ô-vis the European past, no?

CF: Yes, but this is simply a reflection of the way things happened in my family. German migration was puny to Mexico; it was not a big migration. Now the fact is, and I'm sorry about this and I worry about this, but okay, during the 19th century, everybody looked toward Europe in the cultural elites of Latin America. France, especially, was the fashion and that was it. You had to be French and know French, etc. Now we've lost Europe. Now we're oriented toward the United States, and that is a pity because we have to retain our European roots, our European identity, and especially our economic ties with Europe. We cannot be as dependent as we are on the United States. Thanks to President Zedillo, Mexico has entered the European Union, we are members of the European economic community, and that is good. We must diversify. This is one of the things that Jose Marti insisted upon very much: Diversify, do not depend on only one buyer, or you will be the slave of that buyer.

AC: Do you see Mexican art turning that way, turning back to Europe?

CF: No, I think that Mexican art is very universal. When you speak of the nativeness of Diego Rivera and Siqueiros and Orozco, well, let me remind you that Rivera owes everything to the Renaissance muralists. Orozco owes everything to German expressionism, and Siqueiros owes everything to Italian futurism. They are not that native if you look at what native art, Indian art, is in Mexico. It has nothing to do with the modern art of the muralists. They derive very much from Europe, although they strongly denied it.

AC: How do you re-create the personalities of these very distinct historical voices like Rivera or Frida Kahlo and Xavier Villaurrutia? How much freedom do you feel in giving them voices?

CF: The freedom that any novelist who introduces historical figures has. Tolstoy had Napoleon on the scene; that's a big one to swallow. It is an old tradition of the novel to have current or past historical figures appear and speak and walk, and you try to give them as much autonomy as you would like. But they are part of a scheme of the novel, and they fit into that scheme, then you give them as much freedom as you can.

AC: One of your characters, Orlando Ximenez, says, "The difference between us and Proust is that he finds old age and the passage of time in an elegant salon in French high society, while you and I, proudly Mexican, find them in a funeral parlor."

CF: (laughing) Yes, what an absurd personality and what a mysterious personality, that Orlando Ximenez. When he reappears in the life of Laura Díaz, it is to go to the burial of an old friend. That's where they have this Proustian scene where all their old friends of the 1930s reappear in the 1970s rather worn for use. It's curious that when you meet old friends in Mexico, it is usually at funerals. And then you're very surprised, or as García Márquez usually says, "Do you realize how many people are dying today that didn't used to die yesterday?"

AC: Right. So what might this age and passage of time mean for a character like Orlando Ximenez, or for Mexicans in general?

CF: Ximenez is a rather frivolous character, of course. He has lived for pleasure, he has lived for the day, he has lived for a youth that is no longer there. What a difference with Laura Díaz, who in her fifties and sixties finds herself, becomes a photographer, becomes an artist, and discovers that youth is not something you lose. Youth is something you win. That is the difference. There are people, and I hope I count myself among them, who think that youth is something that you conquer every day.

AC: What about the painting of Adam and Eve by Laura's son, Santiago? It seems extraordinary in a culture that traces its roots back to a sexual betrayal by La Malinche and Hernan Cortes.

CF: Well, I had a very beloved son who died last year at 25. He was an extraordinary poet. His book of poems just appeared in Spanish. He was an extraordinary artist and painter. Watching him paint and do all he had to do, I saw this constant need he had to rescue images from their sinful context and give them kind of artistic benediction, to say "this is not true." Adam and Eve did not sin, they did not fall -- they ascended. They went up. To have remained in Eden would have been horrifying. We would have been the pawns of a cruel, almighty god. Thanks to what is called "The Fall," we rose to our humanity.

AC: It seems that throughout history, artists in Mexico and Latin America have been better able to fill political roles or convey political messages than those in the United States, whether it's the muralists that we talked about or whether it's a poet trying to become a president. What might be the difference in the role of the artist in the U.S. and in Latin America?

CF: You have had a strong civil society almost from colonial times. You have also had great, great problems because, okay, you achieve independence in the 18th century and freedom and life and the pursuit of happiness, but you do not grant it to blacks, you do not grant it to women. In Latin America, the things we have not achieved yet have been achieved because writers have spoken out for those who have no voice. As civil society has grown in Latin America in the past 30 years, let's say, there is less and less need for writers to be spokespersons. People have organized. There are nongovernmental organizations and there are barrio associations, and there are unions and agrarian co-ops. There is the feminist movement and the gay movement. A million things that diversify society and make the role of the artist less important. We're back at square one: What is the responsibility of the writer? Basically, it is in writing. Maintaining language and imagination is an essential act for the well-being of a society. But then we're also citizens. And as citizens, we're free to vote, to manifest our ideas, or to keep quiet if we want to. It's a more modern situation than the one my generation went through when we felt a great need to speak out in the name of those who could not speak.

AC: What, ultimately, is the goal then, for the writer in Latin America or elsewhere?

CF: The writer is telling us basically that history is not over. Against these fantastic inventions that history has ended, the writer is saying, "No, history has not ended." We must maintain an open discourse. We cannot shut history down because if we do, we'll be prey to powers that incarnate history without consulting you. The writer says we must imagine the past, the writer says we live in a variety of cultures, and the writer says that the windmills are giants, believe it or not. ![]()