APD

Jail first, questions later?

By Jordan Smith, Fri., July 25, 2008

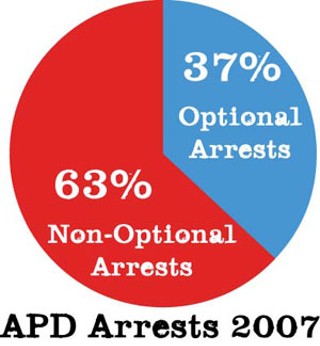

According to a report released Tuesday by a coalition of local advocates calling themselves Austin Public Safety Solutions, more than 36% of people arrested and booked into jail by Austin police in 2007 could instead have been issued a citation and released, saving city taxpayers at least $5.4 million.

Of the 43,418 people arrested and booked into the Travis Co. jail last year, 9,902 were arrested on straight class C misdemeanors – everything from failure to wear a seat belt to possession of drug paraphernalia – which carry a maximum penalty of up to a $500 fine but do not actually include the possibility of jail time. Also in 2007, APD officers arrested 5,910 people for nonviolent class A and B misdemeanors for which "cite-and-release" was an option – including driving with a suspended license, certain criminal mischief and graffiti violations, and possession of up to four ounces of marijuana.

Concerned about overcrowding in county jails and overburdened county budgets, state lawmakers last year enacted House Bill 2391 in order to give police the cite-and-release option for a slew of low-level offenses. Authored by Rep. Jerry Madden, R-Richardson, and carried by Sen. Kel Seliger, R-Amarillo, the bill received nearly unanimous support in both houses (only two voted against it) and was signed into law by Gov. Rick Perry on June 15. The policy was quickly adopted by several major law enforcement agencies – including the Travis Co. Sheriff's Office. TCSO officials estimated that some 7,000 people were booked into jail in 2006 for offenses now listed under the new law. Most of the people would have qualified for cite-and-release, Sheriff's Office spokesman Roger Wade told us last summer, which would have saved the county about $1.2 million. In reality, Wade said this week, the agency will likely see an "even bigger savings" when other cost factors – like the cost of gasoline – are included. "We are encouraging our folks to use it when they can," he said.

The law does not eliminate the possibility of eventual jail time for the class A and B misdemeanor offenses – if convicted, a defendant could get up to six months in jail for a class B offense or up to a year in county jail for a class A offense. But the cite-and-release option allows officers the option of ticketing the accused, who then must appear before a magistrate court for a hearing on the charged offense before being released on a personal bond. Under the provisions of HB 2391, only people who have proper identification, have committed the offense in the county in which they live, and are not also facing more serious charges (or have outstanding warrants) are eligible for cite-and-release.

Moreover, police still retain their discretion to arrest for any of the listed offenses – particularly where they feel that there is "good cause shown" to do so (as in a situation where there is a risk that the person might injure himself/herself or someone else).

While TCSO has embraced the new law, the APD has not – last fall, police officials said they were "reviewing" it to see how it fit in with existing APD policy. Nearly 10 months after HB 2391 took effect, police brass are apparently still mulling it over. In May, APD Cmdr. Sean Mannix told the Chronicle that cite-and-release would create a policy problem: Specifically, that because APD has jurisdiction in three counties (Travis, plus Williamson and Hays, which encompass small areas of the city) and because two of the three counties weren't yet following the new law, in order to "maintain a consistent" policy citywide, APD had decided not to adopt the new law. Of course, since TCSO had already embraced the cite-and-release option, there was already a problem of inconsistent law enforcement policy.

When asked about cite-and-release during a May 14 council work session, APD Chief Art Acevedo said the department does follow cite-and-release for "some of the folks if we can [positively] identify them" (as required under the law), but the problem was "with marijuana" and that Hays and Williamson county authorities wouldn't abide by cite-and-release for minor pot possession. On Tuesday, however, APD Lt. Donald Baker said that Acevedo (who is out of town this week) is (now, apparently) planning to get all the law enforcement stakeholders together in Austin's three counties for a "roundtable" talk about what it would take to implement a consistent policy for the whole area – "so we can look at everybody's needs and look at the most effective way to do this," he said. Among the questions – still pending after nearly a year – are how to make sure that persons receiving citations know exactly when and where to report to court. The Police Department hasn't acted on any of this in the last year, Baker says, because of other priorities – including departmental reorganization and retooling important policies on use of force. But, he said, "It's definitely been on our radar."

According to numbers gathered from APD by the new Austin Public Safety Solutions coalition – which includes members of the ACLU and the LULAC – it isn't clear whether police have availed themselves of the cite-and-release option since it took effect Sept. 1, 2007. That contradicts Acevedo's May assertion – though it is hard to determine from the data APD provided how many people might have avoided jail if the Police Department had adopted the option in a timely manner. In all of 2007, 1,393 people were arrested and jailed for minor pot possession, 543 for criminal mischief, 68 for graffiti, 2,294 for driving without a valid license, and 1,608 for theft of less than $500 – all offenses covered by HB 2391. But the raw numbers don't reflect how many of these arrestees would meet the other conditions of the law.

The cost of processing low-level arrestees into the criminal justice system is high – not only to the individual, burdened with an arrest record even if never convicted (which can negatively effect employment and housing options), but also to taxpayers. Data provided by APD reflects that taxpayers spend at least $342.94 for each person arrested and booked into jail – a total that includes not only the basic booking cost ($104.45 per arrest), the cost for fingerprinting ($10.56 per arrest), and the cost of magistration ($17.45 per person), but also manpower costs, which, conservatively, add up to about $125.17 per arrest. Even this is likely a low-ball number, however. The data APD provided is based on the salary of one three-year-veteran officer (relatively low on the pay scale) completing the arrest-and-book process in just three hours, the "best practices average." APSS argues that APD doesn't monitor for best practices and "tends to use one or two officers" for each arrest, which they "conservatively" estimate at $195.30 in officer time for each arrest. Factoring in all four costs – booking, printing, officer salary, and magistration – the APD spent about $5.4 million in 2007 to jail 15,812 low-level nonviolent offenders. (In 2006, the department arrested slightly more people on the same charges, spending roughly $5.5 million.) These figures are certainly low estimates, as they do not include either the true cost of manpower nor any of the additional jail or court costs that come out of the Travis County budget.

Given the stresses on the city's budget, "if we really want to be fiscally responsible, we have to have all these options on the table," said Austin Police Association Vice President Wuthipong "Tank" Tantaksinanukij. "This is really talking about, in reality, expanding the resources available to officers. We're open to anything that will help us do the job better and free up the manpower of our officers."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.