The Fantastic and Utterly Disreputable History of the Bevy of Sin Known as Guy Town

Before It Was the Warehouse District, It Was the Whorehouse District

By Ian Quigley, Fri., Jan. 26, 2001

It's Friday, and you're going to get tanked in sophisticated company. You head on down to the Warehouse District, and plop yourself at any one of the area's finer watering holes: Sullivan's, Cedar Street, Saba, Fadó. Martinis swirl, pints settle. You lean back and watch the beautiful, moneyed people swan to and fro and congratulate yourself on your fine taste. After all, Fourth Street and its environs probably contain the highest density of hoity-toity nightspots in town.

It wasn't always that way.

A century ago, you could be standing on the soil in front of any of those establishments and facing a different choice entirely. Sure, you'd be looking for romance. But these buildings contained the type of romance one paid for. Some houses would be high-class, some less so, and some downright ugly. Some had only black women inside and some had only white or Hispanic. Some would be connected to saloons or pool halls or even grocery stores through a back door. Others would be cramped little apartments with doors opening into filthy alleyways. Rotting garbage could be found stinking up the streets; dogs and hogs would run wild and get in your way.

You'd walk inside and pitch a nickel into the coin-operated piano. You'd pay about a quarter for a beer, or 50 cents for a whiskey, which was pretty stiff, considering the same would get you a meal at the best restaurant in town. If you wanted a dance with one of the numerous ladies loitering inside, that might cost too, usually about 50 cents for a single twirl. One could also arrange a possibly carnal "date" with a dancer in one of the darkened back rooms for about a dollar, and such trysts usually lasted shorter than a dance might. Brawling, singing, "vile talk," and "abusive language" were common. Knives were pulled, bottles broken, guns fired.

(Lawrence T. JOnes III Collection, Austin)

This neighborhood was home to hundreds of prostitutes, slowly building momentum from the early 1870s until its eventual shutdown by moral crusaders in 1913. In 1880, for example, there were about 100 prostitutes, or fully 5% of Austin's female population age 18-44. This part of Austin provided them with an opportunity to ply their trade; it attracted troublemakers and politicians alike. In city documents, it was classified as the First Ward, bordered by the river, Guadalupe, Colorado, and Fifth Street. Everyone else called it Guy Town.

Westward Ho!

Guy Town started with a slow simmer. In 1870, Austin's population was a piddling 4,428, and the city was a bucolic, dusty place. Peeking at its laws gives insight into the concerns of citizens then: The 1874 Ordinances banned "maliciously or mischievously ringing any door-bell." It was illegal to "run any railway engine or car at a speed greater than five miles to the hour." Even kite-flying in public was forbidden. Vagrants, rather than the shiftless or the dot-com casualties, were defined as "all able bodied persons who, not having any visible means of support, live idly and without employment." It was a misdemeanor to drive "any horses, mules, jacks, beeves, cattle, sheep, goats, hogs, or other animals, in droves through Congress Avenue or Pecan Street [now Sixth Street]." It was also illegal to keep "a bawdy house, a house of ill-fame; or house of assignation." That is to say, it was illegal in the city of Austin to operate a brothel.

The City Council first banned prostitution in June 1870 when it prohibited "fandangoes or dance house[s] where lewd women or persons who have no visible means of support are admitted." Even quaint little towns needed such laws: Prostitution's sobriquet as the world's oldest profession is deserved, and it was everywhere. The Civil War, far from being a stoic, asexual conflict, stimulated a booming sex trade in both the North and the South. In 1864, Washington, D.C., had grown so accustomed to its brothel troubles that its provost marshal not only listed them and their occupants, but actually rated them on their quality (ratings were given in numbers 1-4; "low" and "very low" were reserved for special cases). Prostitution was everywhere, and migrating troops had brought attendant swarms of loose women wherever they went. The bulk of the nation was thoroughly acquainted with the trade, and Texas was no exception. What's more, the Texas Central Railway was coming, and a railroad would soon connect Austin to the rest of the world. The final spike that completed the passage to our doorstep from Brenham and Hempstead was driven on Christmas Day, 1871, and over the following 30 years, Austin's population quintupled. Crime, the city architects surely felt, could not be far behind.

So when the council addressed prostitution for the first time, the city was still small enough to be dealing with small-town matters (after passing the fandango ordinance in 1870, the council turned its attention to a petition "praying that the nuisance about Mrs. Huberich's dogs be abated") but starting to think big. It prided itself on being an up-and-coming Western city: In 1871, the council would extend an official invitation to that most Western of writers, that bold utterer of "Go West, young man," Horace Greeley. The City Council glowingly called him the "the veteran leader of American journalism and philanthropy ... the advocate of the working masses, their education, and our country's progress" in hopes of wooing him this way. While Greeley would decline (he was only in Giddings, but cited rain and lost luggage in Ledbetter), the railway would bring Austin her fortune. It was a time, the council may have felt, to prepare for the future. Others thought so, too: The same day it heard the dog complaint, the city heard a petition from one Charles Cooney to open an establishment that served liquor. In a decision the council would later regret, it gave him the license. Cooney would figure prominently in the courts for years to come, and not in a good way.

Red Light Gets a Green Light

With an anti-prostitution measure firmly impressed in the city ordinances, Austin was legally equipped to handle any red-light problems it might encounter. Unfortunately, the police force did not try particularly hard to enforce the law. While hassled often, prostitutes were only rarely arrested for plying their trade. Charges of assault, public intoxication, and use of abusive language were far more common, even when the arrestee was a known prostitute. Historian Anne Butler reported that from the years 1876-79, only 22% of prostitute arrests involved prostitution charges. David Humphrey found similar numbers: From 1880-98, 26% of all prostitutes arrested were charged with being "lewd women;" the rest were busted for something else. Thus, while the city of Austin felt compelled to ban prostitution proper, it was much more comfortable arresting prostitutes who were making spectacles of themselves rather than those quietly conducting their business. Rarer still was the charge of "running a house of ill-repute" filed. In 1876-79, only nine individuals were so arrested. Moreover, three of them were men, and two of these were holders of ostensibly legitimate business besides (both saloons).

Rowdy prostitutes, angling for revenge, frequently called the police on one another. For example, on Nov. 11, 1879, Ella Wright turned in Ella Warren for disturbing the peace. The same day, Lizzie Warren turned in Ella Wright for the same thing. (Ella Wright must have been quite a woman; she was arrested a half dozen times in 1878, usually on assault charges. She does not, however, hold a candle to Ann Howard, who managed to get arrested more than 50 times over a 10-year period, 1876-85.) Prostitutes regularly got hauled off in groups that had been fighting; one gets the impression that, annoyed with their peers, they called the police frequently to settle disputes. However, it is important to note that the Austin constabulary had no qualms about readily identifying prostitutes as such without immediately running them out of town. Many women can be found in the arrest records with occupation listed as "prostitute"; it's quite obvious the arresting officer knew who and what he was dealing with. At the end of the day, Austin was a civil society: If trespassed against, prostitutes had a right to redress their legal grievances like anybody else.

That's not to say they didn't get in trouble. For instance, on Dec. 3, 1878, Lottie Walton was turned in for intoxication by Katie Franklin, who herself was arrested some weeks later on December 27 for "blowing [a] police whistle." How Franklin got hold of such a whistle in the first place remains a mystery, although it's worth noting that the police and the prostitutes had difficulty sustaining antipathy toward one another. At least one police officer lived in a building that housed a known brothel; another adopted a prostitute's daughter. Intermingling between the opposing forces had become enough of an issue for the City Council to decree that officers were to enter bagnios only in the line of duty. The Austin police did have business at the brothels, and it was not always busts. Longtime madam Sallie Daggett called the police for assistance on more than one occasion, despite embarrassing episodes wherein she was hauled into court on charges of theft of money from sleeping patrons. (Her usual, and highly successful, defense was that the client had drunkenly spent it.) Such thefts were common and often required special tactics to wiggle out of being caught red-handed. Another esteemed madam, Fanny Kelley, "found" a "lost" wallet thick with $480 that a customer claimed was stolen. Austin police ransacked madam Blanche Dumont's place over a $12 theft and recovered $8, assorted personal items, and a necktie.

(Austin History Center PicA13826)

Residents occasionally complained about the situation, but the city was loath to do anything about it. Austin's mayor, T.B. Wheeler, was much more comfortable getting outraged over things like gas lamps. In the June 2, 1874, City Council meeting, he sternly intoned, "I cannot conscientiously sign the resolution which requires the city to close contract with Sylvester Watts for 20 lamp post lamps and fixtures at $50 each." The council unanimously overrode him. The mayor wrote lengthy diatribes about what he perceived to be the city's shockingly poor fiscal health to the paper; he beamed at the opportunity to be a public crank. In short, the mayor directed all of his grandstanding ammunition at Austin's wallet rather than below its belt. In the meantime, parts of the city grew darker, seedier, and more boisterous.

Watching That Language

Neighbors of bawdy houses, especially those occupying the bustling First Ward, complained of ragtime music and "vile talk." Prostitutes and other citizens were frequently arrested on charges of "abusive language" in Guy Town. Doubtless the definition of "abusive language" was up to the arresting officer, although it might not be as colorful as one might be tempted to think. As historian Thomas Lowry noted, most disciplinary actions taken by either army in the Civil War were for minor utterances such as "god damn you" or "son of a bitch." One Pvt. James Ducy, of Company B, 16th New York Calvary, told his superior, "Lieutenant, you are a damned son of a bitch; you can suck my ass, I'll mash you and you shall pay for it." Compared to the other ho-hum insults in the literature, his contemporaries must have swayed in awe at his oratorical pyrotechnics. Today, he wouldn't get past grammar school. Lowry himself laments, "What we hear ... are the meat and potato curses of angry, usually drunken, men, whose contributions to the science of malediction seem sadly lacking." The implication is that hardened soldiers in the 19th century were unable to produce truly shocking invective. If soldiers couldn't curse, what is to be said of the civilian population? When mishaps occurred in Austin and "some cursing was indulged in," the "cursing" was probably pretty tame.

This is not to say that citizens took no offense: A state law existed that dropped murder charges down to manslaughter if the deceased directed "insulting words toward a female relative" of the accused. So fine a legal point was this that "son of a whore" was accepted as defensible but "son of a bitch," being "rather a sudden expression of anger and contempt" but really not directed at anybody's mother, was not. As such, one killer beat the rap because he'd been called a son of a whore, while another was convicted of murder, having the poor luck to be called only a son of a bitch. Concerning "son of a bitch," the Texas Court of Appeals of 1887 couldn't help adding, "It is a lamentable fact that this mode of expression is of too common use in the country."

Compared to certain foulmouthed citizens today, prostitutes arrested for "abusive" (or, in at least one case, "effusive") language likely had limp-wristed linguistic repertoires. However, their use of razor blades and broken bottles in brawls is well-documented. What they lacked in creative vitriol they made up for in violence.

Taking Back the Night, or at Least My Own Neighborhood

Violence escalated the worries of locals, and at least one cadre banded together to try and remove Guy Town altogether. Charles Simms, a resident who lived at the corner of Guadalupe and Third, had such ideas. The father of five teenage children, two boys and three girls, Simms watched his neighborhood decline with growing distress. His daughters, the youngest one at 12, were living and playing uncomfortably close to fast women (the legal age of consent in Texas at that time was an astonishing 10 years old); his sons were tempted by gambling and vice. Together with other concerned citizens, Simms petitioned to have Charles Cooney's place shut down in 1874. Cooney, who operated a grocery-cum-fandango parlor, was encroaching on Simms' previously pristine neighborhood.

Simms' efforts fell on largely deaf ears. Cooney transferred control of his place to one of his minions, and his liquor license continued to be renewed by the city. Cooney himself was constantly getting arrested for various infractions, many of them violent. One busy morning in January 1876, Cooney found himself arrested for "malicious mischief," "offensive language to Sophia Lightfoot" (twice), "offensive language to Paul Lewis," and "offensive language to Julia Kimball." From December 1880 to August 1881, he was in court no less than four times. One of these episodes required that the police impose incarceration on a determinedly tardy witness; in another, the Austin Daily Statesman smirked that Cooney was "a denizen of the First Ward who so often figures in the courts." The overwhelming majority of Cooney's arrests have to do with assaulting women, probably prostitutes and possibly in his employ. These women, transients all, never stayed in Austin long enough to be registered in the city directory.

Undeterred by the paper's flippant treatment of his dastardly neighbor, Simms again rounded up a posse of friends and neighbors, this time to prevent the City Council from granting any more liquor licenses to anybody in the entire First Ward. The group submitted a petition on Aug. 17, 1875, and the council received it. In a fleeting two weeks, the very next time the council met, it granted no less than five new liquor licenses in Simms' neighborhood. In a city of some 10,000 residents, such a proliferative burst of alcoholic activity is remarkable. The Austin City Council was going to build a red light district on Charles Simms' porch, and there was nothing he could do about it. The next month, it approved three more liquor licenses in different parts of the city. The month after that, another two.

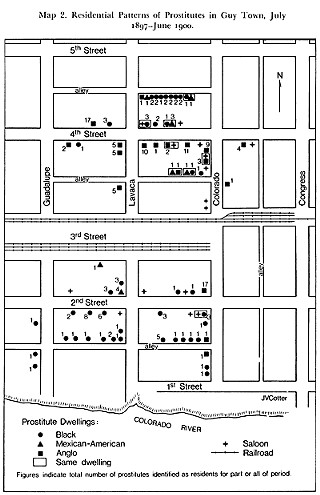

July 1897-June 1900

This map shows 187 prostitutes living in this 10-block area.

(Source: David C. Humphrey's "Prostitution and Public Policy in Austin, Texas, 1870-1915" in Southwestern Historical Quarterly 86 (April 1983) p.473-516)

A Flourish of Strumpets

Saloons frequently operated as, or in conjunction with, houses of ill repute. One of the liquor licenses granted in response to Simms' 1875 petition was to Sam Garone and Joe Massia, for their "theatre and billiard hall saloon" located on Pecan Street in between Congress and Colorado. A little over a year later, they found themselves in hot water for "keeping a dance house." In April, Garone was assaulted. In July, he was arrested and charged with eight counts of "keeping and allowing a dance house attached to a saloon and where prostitutes resort."

Some of the brothels in Austin were quite impressive in decorum. The redoubtable madam Blanche Dumont, who was present in Guy Town virtually from its inception to its dismantling in 1913, managed to make quite a life for herself, and she became a fairly strong presence in the community. In the mid-1880s, she purchased her own building that she had been sharing with at least nine other prostitutes since 1882. It was draped in carpeting and hangings; Miss Dumont herself had grown in stature and wealth and had long since adorned her person with expensive fabrics and jewelry. This outward appearance of wealth, while certainly a comfort to those patrons seeking a little class, did not stop her from running up unpaid bills to the local lumber yard and requiring financial aid from a City Council member to finish paying off her house. Her address, 211 W. Fourth, is now occupied by a building that houses Oilcan Harry's.

With a strong market and a captive audience, Guy Town became a way station for transient working girls. In the two-year span of November 1879 to October 1881, 177 of them had at least passed through town, if not hung around. What's more, the Texas state Legislature didn't meet at all during that span, and the convergence of so many male politicians in one city tended to boost the sex trade and the number of its employees. With the arrival of the University of Texas in 1883, Austin prostitutes had all the clientele they needed. One vice crusader claimed to have counted 100 UT students out looking for love in a single evening in 1913, not unlike a sojourn to Bob Popular today. But on the whole the Austin of the late 1800s seemed relieved to keep the menace confined to a particular part of town.

So ready was the city to acknowledge Guy Town as its red light epicenter that in 1887, the council considered making it illegal to rent property outside Guy Town for prostitution purposes. This suggests, of course, that renting property inside the First Ward for them was acceptable. This tacit licensing of bordellos in the region very nearly passed, and only an 11th-hour change of heart of a few city aldermen defeated it. Even though the measure didn't pass, the gauntlet had been thrown. In 1900, police relocated prostitutes from other parts of the city to Guy Town. The Texas state Legislature granted cities the right to actually legalize and license prostitutes in 1907, and both Houston and Dallas did so for a time. By refusing to license its own harlots, Austin set itself apart from these cities, but only on the surface. In practice, it was little different. While the city seemed content to let prostitutes conduct their business quietly, it did bust the more obstreperous ones. It also selectively arrested more nonwhite prostitutes.

Race, Vice, Violence, and the Vociferous Response to the Christmas Eve Murders

Prostitution in the late 19th century, like the rest of the United States, was a racially mixed bag. Wrote Pvt. Alfred Bellard in his diary, Washington's red light district was "occupied by black and white, all mixed together ... you pays your money takes your choice." Austin was no different, and, despite mild taboos, the races mixed occasionally in the sexual trade and everyone knew it. The Statesman even once upbraided a white man for being "brute enough" to be discovered in a black bordello. Other than having to tolerate insults at the hand of the local paper, nonwhite prostitutes also had selective enforcement of the law thrust upon them. While Austin police made an effort at fairness in the 1870s, by the late 1880s fully three-quarters of prostitutes arrested were black.

Other than selective enforcement and the occasional sweeping up of particularly egregious or disorderly prostitutes, Austin tolerated the presence of the sex trade for many years. The first serious challenge to the practice came in 1885, when over a nine-month period there was a spate of gruesome murders, usually with knives or axes, some involving rape. The first six victims were black and mostly female, and despite police investigations, no conclusive suspects were found. The Statesman, disgusted, declared the marshal "has not the capacity to intelligently direct the police affairs of the city." That said, the Statesman went on to claim "No ignorant Negro ... committed the crimes. They were conceived, and especially the one of Sunday, with a superior intelligence, and brain work of a high order will have to be invoked to discover the perpetrators." (For more on these serial murders, see also Kevin Fullerton's "Killer Reputation," p.42.)

was arrested July 26, 1876, for eight counts of "keeping and allowing a dance house attached to a saloon and where prostitutes resort."

(Austin History Center AR PI 7/26/1876)

Black citizens petitioned Governor John Ireland to offer a "liberal reward" for the apprehension and conviction of the murderer; the Statesman responded that a committee had been formed and it was "best to wait the action" thereof. The cases were largely forgotten until Christmas Eve, 1885, when two white women were killed. Only then was there a serious uproar: "Last Night's Horrible Butchery," said the headlines. "The Demons Have Transferred Their Thirst for Blood to White People." The day after Christmas, there was finally a call to action. "Midnight Outrages," read the paper. "The People Roused Into Indignation." "A Large Meeting at the State House in Response to the Mayor's Call." And, of course, "Addresses by Prominent Gentlemen and a Committee Appointed."

Anti-vice sentiments rose in anger, but they did not last. For little more than a month, there was talk of suppressing Guy Town, but for all the bluster there was no action. James Phillips, the white husband of one of the white victims, was arrested for her murder but eventually acquitted. His wife, Eula, turned out to have been a sometime prostitute at madam Della Robinson's place. Soon enough, it was back to business as usual for everybody.

Getting It On in the 19th Century

If a tacit acceptance of prostitution in Austin and elsewhere suggests a slightly more permissive society than one is used to hearing about, the frankness of contemporary physicians provides harder evidence. In big, frequently run ads in the Daily Statesman, "Bradfield's Female Regulator" was a medication that was "set specifically on the womb and uterine organs" and relieved "menstrual disorders." The 1880s also saw the invention of the electromechanical vibrator, which was used on patients suffering from "female troubles." Such troubles, nominally labeled "hysteria" or "hysteroneurasthenic disorders," tended to be diagnosed with vague symptoms and treated with physician- or midwife-assisted masturbation. Medical professionals considered this a tiring chore and passed off the duty to somebody else whenever they could.

While public acknowledgment of female pleasure, particularly self-pleasure, was verboten (clitorodectomy was still considered a viable treatment for chronic masturbators), products designed to relieve doctors of the tedium of bringing their patients to orgasm sprang into being and were widely used. By 1904, a publication for physicians titled Mechanical Vibration and Its Therapeutic Application listed about two dozen vibrators, powered by "air pressure, water turbines, gas engines, batteries, and street current through lamp-socket plugs." In the first two decades of the 20th century, vibrator manufacturers began to sell to the public directly, bypassing female sexuality's clinical middleman. Advertisements contained such ambiguous phrases as "all the pleasures of youth ... will throb within you," and by 1918, even the Sears, Roebuck and Company Electrical Goods catalog had several irregularly shaped vibrator attachments for a motor that also could churn, beat, mix, grind, buff, and run a fan. The ad is titled "Aids Every Woman Appreciates." So while [ostensibly male] physicians might have thought otherwise, this period of the nation's history also catered to women's pleasure.

Other medical aids were widely available. Morphine, in particular, was easily procured and often used for recreation or suicide. Prostitute Belle Brown used it to kill herself, for example, while she was living with Della Robinson. R.M. Burton, another despondent Austinite, did the same. Citizens could also obtain abortifacients: At his murder trial, James Phillips revealed that he purchased "chamomile flowers, extract of cottonwood and ergot" for the purpose of stimulating an abortion in his wife. The easy availability of these agents indicates the laxity with which Austin, and other parts of 19th-century America, conducted itself. With permissiveness on a variety of levels, some tacit acceptance on the part of the police force, some ambivalence on the part of the city of Austin, and a sometimes startling degree of licentiousness, it is no wonder that Austin's prostitute population grew substantially at the end of the 19th century.

End of an Era

It couldn't last forever. Strong anti-prostitution sentiments flowered in the early 20th century, and its proponents were eager to link feelings of purity with disgust for disease and unwanted pregnancy. The Statesman suggested that girls on the street innocently flirting had their names "bandied about in the saloons, on the street corners and in the low down, unholy places in the city" and argued for chastity. A Rev. Bob Shuler whipped his following into a frenzied movement, giving sermons and holding large meetings. Among other things, Shuler invoked the looming specter of venereal disease in his arguments against the sex trade. At the time syphilis was incurable, and a disease that produced foul-looking sores, blinded newborn children, and caused crippling dementia proved to be a potent propaganda tool for Shuler and others in Austin who hoped to shut down Guy Town and send its denizens packing.

Their strategies eventually worked. Ultimately, the crusaders appealed to the city's sense of economic base: the university. Dismayed by a noisome moral atmosphere, students, in theory, would shy from coming to the University of Texas, and the entire region would suffer. Faced with such crushing logic, Austin's mayor at the time, Alexander P. Wooldridge, threw his weight around and had Guy Town banned in a tense City Council meeting in the summer of 1913. The Statesman, pro-prostitution despite all of its moral grandstanding, was sourly miffed. The prostitutes were summarily evicted from that part of town and ordered to disperse on Oct. 1, 1913.

The Statesman reported that "the women in the segregated district were rapidly leaving the city or making preparations to leave" on October 2. The next day, it repeated that they were indeed leaving. On the very same page was an even stronger indicator that times had truly changed: A production of the opera Salome was coming to Austin and was stopped in its tracks by members of the clergy on the grounds that it looked salacious. Mayor Wooldridge wired the mayor of Fort Worth, where the show was last seen: "Claimed here opera Salome rendered in your city grossly immoral. Kindly wire me at any expense your just and practical judgment of this play." Mayor W.M. Holland of Dallas replied: "Did not see Salome. Tom Flinty of Dallas News advises me performance is moral." In their zeal to prevent smut from coming to town, upstanding Austinites proclaimed this production to be dirty without even knowing what it was, only expecting it to be an infamous dance routine only whispered about in darker circles. To their great chagrin, it was not. The headline of the article? "'Must Have Confounded Opera With Dance' Says Mayor." ![]()

Ian Quigley is an editor of History House, an online publication that features offbeat history: www.historyhouse.com.