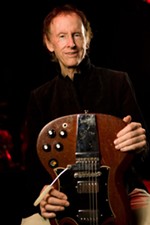

Ray Manzarek: Trying to Set the World on Fire

The late Doors keyboardist at the Garden of Eden

By Danielle Zelisko, 4:20PM, Thu. May 23, 2013

When I was a freshman at Sonoma State University in 2006, I received an assignment that required I interview a person older than 65. As an out-of-state student in my first semester, I only knew one individual who fit the criteria: Doors’ keyboardist Ray Manzarek.

My father befriended Manzarek through his career as a concert promoter, so I called up my subject and split off to Napa for the interview and a tour of his small vineyard. Our chat, which I recorded and transcribed that autumn, hasn’t been published until now.

Danielle Zelisko: First thing’s first. When were you born?

Ray Manzarek: February 12, 1932.

DZ: ‘32?

RM: I’m sorry. February 12, 1939. I just get older or younger, I can’t be sure of which [laughs]. Right at an instant I got older and younger at the same time!

DZ: Do you have any siblings?

RM: Yeah, two brothers – both younger. Rick and Jim. We grew up on the south side of Chicago.

DZ: My dad’s from Chicago.

RM: Yes he is. He’s a north side guy. I went to Everett Grammar School on 34th and Bell Avenue, then I went to St. Rita High School – 63rd and Western. Then I went to DePaul University downtown. Man, was it cool, because everything was there. We were down the street and around the corner from the orchestra hall where the Chicago Symphony played. The World Cinema had all the foreign films; jazz clubs and museums were there too. The Art Institute was within walking distance – the Field Museum, the Museum of Natural History. The Art Institute had the Goodman Theatre, so they had a lot of theater going on. All kinds of things were within, you know, five or six blocks of where I went to school. I could just walk from one place to another.

DZ: What did your parents do for a living?

RM: My father was a machinist, a tool and dye maker as they called them, for International Harvester. He was a good union man, one of those guys who, you know, worked hard to send his sons to college. And my mother took care of her three boys, or four boys, with my father. Jeez, she had her hands full. Four men in one house.

DZ: What was it like growing up in the Forties? How did the war affect your life?

RM: The war didn’t affect me at all. I was just a little kid, so I wasn’t aware of that at all. I mean, I was aware of it. It was something going on, but as I think back on it now, it’s mostly vague memories. I can’t really remember anything about World War II other than running around the street and playing. That’s all we did. We played!

DZ: So you’d say you had a typical upbringing, whatever “typical” is.

RM: Well, unfortunately, today it seems it was very atypical. You know, in today’s terms it was not a typical upbringing at all. My father came home after work about five o’clock, 5:30, and my mother made dinner, and we lived in a neighborhood and we went out on Saturdays and Sundays.

We drove around in Chicago and went to the lake and went to the museums and went to the Science and Industry Museum; went to the forest preserves out in the suburbs. They set aside land for the forest preserves just to look at the forest, and they put picnic benches and parking places, and you could have little barbecue cookouts and, God, we did that all the time!

My father was so good at making ribs and things and putting little baked potatoes into a fire off to the side. They would turn black and you would look at them and think, “These are the worst things on Earth!” But he’d cut them open and they would just be so white and creamy and just incredible! Butter, salt, and pepper, and a cold Pepsi or a cold Coke – God, it was heaven! So I think I had a very atypical upbringing for today, but back then very typical. It was like Leave It To Beaver, or Father Knows Best – one of those kinds of things.

My parents were very supportive, very loving, and I was totally secure. If there’s one thing a kid needs to be, an adult needs to be – if there’s one thing we all need to be – it’s secure. My mother and father made me completely secure. Food was always there. We always had a car to get around in. I lived right across the street from grammar school, so I’d come home for lunch. How many grilled cheese sandwiches with tomato soup and carrot sticks did I eat in my eight years of grammar school [laughs]? So I had a fabulous time.

The park was about – McKinley Park, great park – fishing and basketball courts, a swimming pool, and that was maybe five, six blocks away. About two blocks away was something called Point Playground, where during summer they would have softball games at night and the older guys would come. They’d turn the lights on and we had little 14-year-old softball teams and baseball and football teams from Point Playground, and we’d go around the city playing the other playgrounds and won a couple championships. We had a great bunch of guys, all the local guys! I had a good upbringing, now that I think about it. Piano lessons is something I did. Mom took me all over the place. We did all kinds of things.

DZ: When did you start playing piano?

RM: Oh, about eight, nine years old. Something like that.

DZ: Did any of the politics, especially in the Fifties with the Red Scare or segregation or any of that, affect your life?

RM: Segregation didn’t affect you because it was Chicago and there were lots of black people, and there was the blues on the radio. My God, Chicago. It was outside of Chicago, the home of the blues, that I first heard that music. I must have been 11 or 12. It changed my life.

My mother and father grew up down in an area that was mixed. It was black and white and the whites were Catholic and Jews. And Italians and a lot of Pollocks, like us, and some Irish. There were Germans there too and my father’s Jewish buddies, which I got to meet later on. We went down to Maxwell Street on the south side of Chicago, and my father introduced me for the first time to a Jewish delicatessen. God, was it amazing walking into that. And I forget the name of the place, but I swear I can still see it. I can smell the place in my mind’s nose.

Walking into the steaming tables, steamed tables of corned beef and pastrami, sausages being grilled, hot dogs, Chicago Red Hots being grilled, big mounds of onions and the smell of the corned beef and the pastrami and mounds of sliced rye bread; big vats of pickles; quarts of yellow mustard. The place, it was meat heaven. If I die, I want to go to this place for the rest of eternity [laughs], and just eat all of these good things.

So we would go down there and I would have a hot dog or – mainly a hot dog because I was a little too young to have a pastrami or a corned beef. I don’t think I was quite ready for it. My dad knew the owner and they chit-chatted back and forth. He’d say, “This is my son!” I’d say, “Hello, sir, how do you do?” “You want a hot dog, kid? How ‘bout a hot dog?” “Yes, sir, a hot dog would be great – a Chicago Red Hot!” “You got it, son! Ray how ‘bout you? Big Ray what about you, buddy? What are you gonna have Ray? You want that corned beef, want a corned beef on rye? You got it! What else, what else?”

That was an amazing experience. That was my father’s upbringing and my mother’s upbringing. They were both in the same neighborhood. So, uh, racial didn’t really enter into it at all. Chicago, for me, it was very cool that way. I suppose if you were to ask black people my age, when we were kids, they would say it was racially segregated, which of course it was. But man, you couldn’t do anything in Chicago without being part of the black culture.

DZ: What did you do for fun as a teenager?

RM: Rock & roll! I played rock & roll, played basketball, football, baseball, every sport you can imagine. I went to high school and listened to blues on the radio until rock & roll started. And then I was listening to Muddy Waters, Jimmy Reed, John Lee Hooker, and all of those guys before rock & roll hit. And then a couple of years after I got into those guys, I was learning all that on the piano, so I was taking piano lessons the whole time and getting good at – not so much at piano lessons but getting good at playing the blues and improvising.

Then I heard rock & roll and that was it! Elvis Presley on television and Carl Perkins’ “Blue Suede Shoes.” Jerry Lee Lewis and “A Whole Lotta Shakin’ Going On,” “Great Balls of Fire.” Then on the other side, the black guys were Little Richard – what a maniac!

Little Richard’s band, I think he was probably my favorite. He was just... that band playing “Lucille,” God almighty. Deep baritone saxophone underneath. You could just feel that thing. And a lot of piano players: Jerry Lee Lewis, piano player; Little Richard, piano player; Fats Domino! That was very influential on me.

Fats Domino’s left hand on “Blueberry Hill.” [Sings] “I found my thrill...” and the right hand would go tink tink tink tink tink tink, and the left hand would go bom, bom, bom, bom, dun dun dun. [Imitates “Blueberry Hill” melody] That’s Doors music! [Imitates melody again] It’s almost “Light My Fire.” “Light My Fire” is dun dun don dun don dun dun don dun dun, so it’s just a little bit different, but it’s, you know, 90 percent of what I played with the Doors was Fats Domino, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard-inspired.

So that’s what I did. That and lust after girls, you know. And I went to an all-boys’ high school, so there were no girls. What do you do to get a date? Boy, it was hard to get a date. You know, ‘cause there were no girls and you couldn’t just say to the girl at the next locker, “Hey, you wanna go out on Friday?” There was no girl at the next locker! It was just a bunch of guys. It was like 2,000 sweaty guys. God, it was awful!

Then I got to college and it was coed, thank God, so that was great. Dates were few and far between in high school even though I had the use of the car at 16 years old and got my license. Where do you meet chicks? They would have dances and you’d meet girls at a dance, but you’d have to dance and then invariably they’d go home and you’d go home and very few guys made contact at the sock hop. So it was a sexually frustrating time.

The Fifties were very frustrating. Sexually very repressed, very very frustrating. And yet, teenage years are the hottest time of your life. You’re just a ball of sexual fire. All you can think about is making love to a woman, a girl, and that sort of thing. But, you know, so few of us did. Oh, what a tragedy.

And yet, when you finally meet a girl and you’re in college and actually have a girlfriend, God, it was fabulous! I mean, it’s so great that we’re made as male and female. We fit really nicely. I mean the whole emotional thing and the way the two bodies fit together. Who designed that? What a brilliant idea! And, on LSD, I began to think of everything as an idea – somebody’s idea, something’s idea, God’s idea, of course. An orange – I ate an orange on LSD. Looked at an orange, a slice of orange, and one slice with the pith on one side, that little half-moon, and a little web, a little fiber, clear fiber over the whole thing, and then inside are thousands of little flavor sacs.

Each one has just a little bit of juice in it, and each one of those things are attached to each other, and they’re attached to that little pith. And all of these then go together, these little segments go together to make up this globe. And I bit into that one slice of orange and those little flavor sacs exploded in my mouth, and I thought, “This is absolutely brilliant! I am flabbergasted at how brilliant the design of this thing is, and how they grow on a tree. They’re called nature. Who designed this?!” That was my LSD experience.

DZ: That was in college?

RM: Yeah, yeah.

DZ: Was your wife Dorothy that girlfriend in college?

RM: Yes, yes. UCLA.

DZ: Okay, so did you transfer from DePaul to UCLA?

RM: No, I graduated from DePaul and got a bachelor’s degree in economics at DePaul and came out to UCLA. I’d had it with the cold winters. That’s enough, I thought. I’m going to California where they have hot rods, bikini babes, palm trees, cool jazz. The whole musical thing out here was west coast jazz, Gerry Mulligan and Chet Baker working contrapuntal lines with the saxophone, baritone saxophone, and trumpet working around each other. You wouldn’t hear too much of it on the radio, but every once in a while I would hear it and go, “What is that? What is that?” Because it wasn’t the blues and it wasn’t Chicago jazz – wasn’t east coast jazz. It was west coast jazz. It was clean and fresh and there was an airiness to it. It was amazing.

And then, after deciding to go... I don’t know, maybe I had decided, maybe I hadn’t. It was winter of 1959, early winter, and God it was bleak, just 32, 33 degrees. It wasn’t frozen, but it was still cold, just enough to chill your bones. And there was a little bit of ice on the ground from the night before, and there was a drizzle in the air. It was bleak as hell and just the beginning of December, with months to go. I was listening to the radio, and I heard for the first time poetry and jazz. And was that cool, poetry from the west coast.

It was Kenneth Patchen, and he was reciting a piece of poetry called “Lonesome Boy Blues,” and backing him up was Modesto Briseno. What a name, Modesto, like Modesto here in Central California. Modesto Briseno & the Chamber Jazz Sextet. Chamber jazz, wow. It’s like chamber music, and these guys were doing the Gerry Mulligan kind of a west coast thing. Modesto Briseno with the baritone sax, and Kenneth Patchen said, “Lonesome Boy Blues” dun dun dun, and he kicked in: dun dun dun da dun.

They were playing underneath his reading and I thought, “This is the coolest fucking thing I’ve ever heard. This is so hip. This is so wonderful. I want to be a part of that.” And it’s definitely one of the reasons I came to California.

DZ: So, you went to UCLA. Was that for grad school?

RM: Yeah, yeah. Actually, I was going to go to law school. I did go to law school. I enrolled in UCLA for law school and did law school for two weeks and said, “Whoops! [Laughs] Wrong! This is not the arts.” So I thought, “What am I going to do? Maybe I’ll enroll in the philosophy department and I could study philosophy.” Then somebody said to me, “Hey! UCLA’s got a great film department.” Eureka! There you go: film, that’s it! Perfect! Film is the art form of the 20th century, combining photography, music, acting, writing, everything. Everything that I was interested in all came together with that one art form. I said, “That’s it!”

DZ: Were you politically active at all during the Sixties?

RM: Nope, we were making music.

DZ: No protests or anything?

RM: Didn’t have to. Everybody else was doing it. Our job was to make music. We were political in protesting through “Break on Through (To the Other Side),” “Whiskey Bar (The Alabama Song),” “Unknown Soldier,” you know. “Light My Fire,” my god, all those.

The very existence of the Doors was a political act. And, in fact, Jim [Morrison, the band’s singer] did get arrested onstage. They hauled him off stage! They arrested him in New Haven! They busted him for “inciting a riot.” He wasn’t inciting a riot. He was inciting the police. He was doing a rap on the police and they couldn’t stand it. They just grabbed him and pulled him right off the stage! Arrested an entertainer and dragged him to the jail! We’re watching this going, “I don’t believe this is actually happening. This is totally insane!” But that was America. It was the hippies against the squares. It was the people with expanded consciousness against the straights. It was the lovers versus the killers, as it is today.

It’s no different today. It’s the lovers, those who want to stop the war; those who want to make the world a better place to live in peaceful harmony, ecology. “Save the planet” against the killers. The ones who are fighting that war, who want to fight that war in Iraq, are destroying that planet. So it’s the same thing all over again. It’s the lovers against the killers, and I vote for the lovers.

DZ: Would you say that whatever was going on in the Sixties influenced how you look at politics now?

RM: Ummm... No, I don’t think the Sixties influenced how I look at politics today. I think I just look at politics as a way of taking our tax money. Basically, what do they do? What is it that they do? Well, they take, you know, 25, 35, 40 percent of our tax money. They take our money, called taxes. Okay, that’s cool, now what are you guys gonna do with that money? Take care of the roads, take care of the air, take care of the schools? What’s this war going on? What is this insane war? What is this with Haliburton? How are all those people making money off it?

I mean, what they’re doing with our tax dollars is just criminal. It’s absolutely criminal. So, for me it’s just a matter of just doing the right thing. You know, you vote to save the environment, to educate the children, clean up the air so that you can have good air to breath. You don’t use artificial fertilizer, artificial pesticides. Governments should be sponsoring ways of creating energy through alternative sources, and we should all practice organic agriculture, and then we can laugh and dance and sing!

Also, drugs should be decriminalized. I don’t think people should be put in jail for smoking a joint. I think the use of marijuana and actually going to jail, or going to jail for selling marijuana, that’s insane. I can see trying to keep the big dealers, you know, people who are dealing crack, terrible stuff, heroin, well, you gotta get those guys. Gotta get them off the street. That’s nasty business, those white powders. But that’s a debatable point. Should those white powders be illegal or should they, like a lot of European countries, be prescribed through a doctor? That’s a possibility, too. You could certainly stop those poor junkies.

Man, I’ve known junkies. Those poor people are just... They’re so hung up on their drugs and so strung out that they’ll do anything. They’ll steal, rob, destroy their lives, destroy their families. Crackheads will invariably sell everything – sell the wife, sell the kids, sell everything just keep that crack habit going. You know, wouldn’t it be better to have doctors prescribing it – come in once a week, once every two weeks, to get your fix, to try and keep yourself together and get off this stuff? For God’s sake, you’re ruining yourself. Crackheads and heroin addicts all know they’re ruining themselves; they just can’t get off it. They’re addicted.

So I would definitely legalize marijuana, decriminalize marijuana, and certainly psychedelics. The fact that LSD and mushrooms are illegal is like... Peyote is illegal. The only people who can legally take peyote are the Church of American Indians, the peyote church. That’s good stuff. It opens the doors of perception. Psychiatrists can even use that in a therapeutic way. That was proven to be very effective for alcoholics or heroin addicts.

I know a guy who’s an alcoholic. Said he had an acid trip one time and stopped drinking. Gave up alcohol. I’ll bet you could do the same thing with heroin addicts, too. Same thing with crackheads, say, “Hey, come here, we’re going to open the doors of perception. You’re going to look at your life through hallucinogenics or peyote.” That would be great therapy. That’s all illegal. That’s illegal. A doctor cannot even do it! That’s totally insane, totally insane. It’s like stem cell, totally insane. The fact that, what’s his name, what is our president’s name? Hitl- um? Bush. I thought it was Hitler for a second. George Hitler. George W. Bush [laughs] That guy: what a joke. No stem cell research. He wants to stop that. This country is absurd. Hopefully in ‘08 we can change that around. The lovers can take over the killers.

DZ: You were talking about your drug experimentation. Did that happen when you were at DePaul or when you got to UCLA?

RM: Oh, UCLA. California, more California stuff. I never smoked a joint at DePaul. I never saw any marijuana at DePaul University. DePaul was just strictly drinking beer. That’s all I did at DePaul was drink beer.

DZ: So how long did you spend at UCLA before you stopped college, or did you actually get a degree?

RM: Oh, I got my degree. I got an M.F.A at the film school.

DZ: Is that how you met Jim?

RM: At the film school, yep. We met probably, I don’t know, somewhere late ‘63, early 1964 at the UCLA film school. He got his bachelor’s degree in ‘65, and I got my master’s degree in ‘65, and we formed the Doors. Yeah, I met Jim at UCLA and met my wife Dorothy at UCLA in art class. I wasn’t gonna take it, but I did. I took an art class on how to draw storyboards and draw pictures and pretended I knew what to do, but I was terrible. I had no talent that way at all, but she was in the class. That one class. I took one class that I didn’t have to take, and met my wife, and we’re still together! I had no business being in that class. I was in the film school. I didn’t have to take it. I just took it as an elective. Boy, did that work out. Talk about knock on your lucky wood. And met Jim Morrison at UCLA, too.

DZ: So, what did you and Dorothy do for fun?

RM: Fuck. After that, we went to [laughs], we went to the movies. I mean, she sort of joined me at the film school and came to all the classes. So, we went to film school; we went to the beach; we went to the museums; we went downtown to Little Tokyo for Japanese food on Sawtelle Avenue. And went to art galleries, art openings, art exhibits, art museum, and every movie that came in. When we were in school, it was amazing. The classics, what are considered classics today, were first run movies. Like, “Hey there’s a new foreign film playing at the such and such theater close to UCLA. It’s by Fellini! It’s called 8 1/2!” “What’s it about?” “I don’t know!” “Why’s it called 8 1/2?” “Well, he’s made eight movies and he made a short. This is his eighth movie. He couldn’t think of a title for it. It’s 8 1/2!” We went to see 8 1/2, and it was absolutely brilliant! It was like, “Wow, this is great filmmaking!” So, that’s what we did. We were students and made movies.

DZ: Did your work with the Doors affect your relationship with Dorothy?

RM: No, Dorothy was right there with us. Dorothy actually worked and supported me and Jim. When I ran into Jim on the beach and we decided to [start the band], he sang those songs to me: “Moonlight Drive,” “Summer’s Almost Gone,” and “My Eyes Have Seen You.” I said, “Oh man, these are great. We’re gonna get a rock & roll band together. We’re gonna go all the way. We’re gonna go all the way to the top. This is going to be incredible.”

He was really handsome. I didn’t tell him, “You’re so handsome. The girls are gonna love you!” But I thought to myself, “My God, the girls are just gonna love this guy. The music I can make with his words is just going to be fabulous.” So I asked him where he was living, and he was living with a friend of ours, a mutual friend, Dennis Jacobs. I said, “You’re living with Dennis? And you sleep in there?” He said, “No, I sleep up on the rooftop of the apartment building.” Dennis was on the fourth floor of the apartment building and Jim slept upstairs – slept out on the roof. I said, “You can’t be sleeping on the roof! Man, you’ve gotta come live with us.”

We started working on the songs like that, and Dorothy supported us. So Jim had the bedroom and then Dorothy and I took the living room, with the mattress, because it had a heater and we could stay warm at night. Jim had an electric blanket so he didn’t need a heater. Then he got the bed that didn’t have the heater. And the three of us lived together. Dorothy worked and we would take her from – we lived in Venice – and we would take her to work, drop her off, and go to the UCLA music school where they had pianos. We would go down into the little practice rooms and practice. Jim would work on his singing. We worked on his song structure, and I would play the piano, figuring out chord changes. Boy, that was fun. We had no money, but it was a lot of fun.

DZ: And then you started to make money.

RM: Oh yeah, well that was fun, too. That was even better. We got to buy a house! Imagine buying a house and being students, kids. Yeah, at one point we were actually able to buy a house. Well that was a great deal. I mean, everything was fun. We had a great time.

DZ: This probably seems like a no-brainer question, but what was it like being in a rock band in the Sixties?

RM: It’s cool. It’s too cool. It’s... what did we used to say in the Fifties? It’s the ginchiest. They used to say that. Teenage rock & roll movies in the Fifties were hysterical.

Yeah, it couldn’t have been better. I mean it was great. People loved you and you got to play Madison Square Garden, center stage at Madison Square Garden. You got to have a great time, and then after it was all over, your accountant would collect a check for mucho dinero. Then you’d get on a plane and fly first class back to Los Angeles. God damn, man, we had enough money to buy a Mercedes, so we got an old Mercedes. We didn’t get a new one. We got a classic Mercedes, classic, and this cool little house – little two-bedroom house, very stylish, very nice. It was a nice little two-person house, sort of like this place. It was even smaller than this, but any student would say, “That’s the way I wanna live!”

We were so lucky to find it. The only problem was that Jim Morrison became an alcoholic. He discovered whiskey. His family had a genetic predisposition to alcoholism, and once he started to drink, that was it. The other guy came out; speaking of psych majors, the other guy came out, Jimbo came out.

“Who’s that guy? That’s not the Jim Morrison I put the band together with. That’s not the Jim Morrison that lived with Dorothy and I. That guy was funny.” Jim Morrison was funny. He was witty, a great poet, intelligent, well-read, literate; couldn’t have been a better guy to hang out with, really terrific guy. And this guy, I thought, “This guy is really good. Here’s what we’re going to do: we’re gonna do rock & roll, then we’re gonna make movies. Then, by that time, Jim will turn 35. Hell, that’ll be a good 10, 11, 12 years from now and then we’ll go into politics.” And, “Somebody,” I thought, “Somebody, somebody from show business is going to become President of the United States. And it’s gonna be Jim Morrison.”

That was the old Jim Morrison. That was pre-drinking. Pre-drinking Jim Morrison could have been President of the United States; it’d be a whole different country. It would be like if Bobby Kennedy had been President of the United States, too. They killed Bobby Kennedy. Jim would have been a lot like Bobby Kennedy. But Jim got seduced by the bottle and something in that bottle clicked and allowed a trap door to open up – shooop – and out came this slout, this bad person.

He was a mean drunk, Jimbo. Jim lasted until 27. And on July 3rd, 1971, Jimbo killed Jim Morrison in Paris. We don’t know how. We don’t know what happened. Never gonna know what happened. We don’t know what drugs were involved, any drugs, no autopsy on the body. That’ll be one of the mysteries of rock & roll. What killed Jim Morrison? I don’t know.

DZ: How did his death affect your life?

RM: Well, it affected our creative life, that’s for sure, because Jim was no longer with us. But, you know, I can’t say that any of us were surprised. It was like, for two years, two-and-a-half years, he was on a slide – a serious slide downhill. We tried to stop him, but there was no stopping him. And he realized it. We had an intervention with him, John [Densmore, drummer] and Robby [Krieger, guitar] and I, and we sat down and we said, “You’re drinking too much,” and he said, “I know. I’m trying to quit.” “Well, okay man. Anything we can do to help you? We want you to quit, too.” And he said, “Well, I’m trying,” and obviously he didn’t. So, it wasn’t as if it was a surprise. He did himself in. He just kept drinking, and drinking, and drinking, and did himself in in Paris. Death in Paris.

DZ: What have you learned through the years of being in the music business, and how has it changed your outlook on life?

RM: Music is one of the great art forms and it’s the only art form that the performance, the act of doing it, is called “playing.” You play music. You don’t play a painting; you don’t play a novel; you don’t play a poem. You play music. So, obviously, it’s nothing but fun working with something totally ephemeral; working with ether; working with vibrations. Sounds are nothing but vibrations in the air. And it’s instantaneous. It’s here and gone. I play a chord on the piano, release it, gone. It was there for that instant, and then it’s gone. That’s what’s great about live performances, is that it’ll never be that way ever again. It’s just that one time. The audience that’s there gets to see it, perform with us in that ritual that was created in the Doors, and then it’s gone. So it’s like a Zen moment in time.

I think what you learn from being alive on this planet is that you better dance and sing and have a good time. That’s the whole point of it. You wake up every morning and think, “Boy this is gonna be fun. We’re gonna have some fun today! Oooowee.” You have to approach life with an excited outlook. I just read the thing about a guy whose dog has turned 16, and he’s celebrating his dog’s birthday. He said a friend of his, so a writer, an English writer, said, “My dog has taught me more about life. Every morning, I get up in the morning, that dog just comes up to me and goes, “Let’s go! Let’s have some fun! Hi, hi, hi!” You know how dogs slobber and their tongues are hanging out and they shake and they wiggle? He said, “That dog wanted to live each day for just excitement and fun.” And I realized, “My God, this is just a dog! I’m a human being! I can use my intellect to have way more fun. I can go to a museum, I can get a book, I can see a film, I can see art.” It’s all there, all the creativity of mankind.

And what’s great now for you guys just coming up is that everything is there. All the music of the Earth is there on CD. You can get all the movies; 90 percent of the great movies are available on DVD. It’s all there! You don’t have to skimp on any of it. It’s all available to you. The libraries have always been there, but now you can add all the music on this entire planet, and all the films that have been created and what a fabulous, fabulous time to be alive.

It’s a great time to be alive because it’s all there waiting for you, especially for you guys, to control it, to manipulate it, to make it whatever you want to. That’s what we learned at UCLA. That’s what the Sixties were all about: “This is my planet. I can do anything I want with it. So can all the rest of us.” And what did we want to do, in the Sixties? We wanted to make love, not war!

Right now, we want to make war, not love! Hopefully, in 2008, we’ll start to think: “Wait a minute, let’s make love, not war. Let’s do that! Let’s love each other, love the planet.”

So, it’s an exciting time. You guys are gonna be entering into your adulthood, 21, hopefully just as things begin to change over into a new way of thinking, and the destiny of the planet is under the control of the young people. Everyone that’s got an iPod. If you guys all get together, my God, you could actually change the destiny of the world. And that’s what we tried to do, too, and we did in our own little way. But we didn’t succeed. You guys have to pick up after us and carry it forward. Carry the good fight forward. Fight those bastards. Those bastards want to destroy it. They’re dark and evil. They will destroy this planet. The lovers have to save the planet.

DZ: Would you say that’s what you value most, is just waking up, living each day to the fullest, and loving the planet?

RM: Being alive, yeah. Being alive on this planet is a real trip. There’s so much to do. The thing I value the most is my wife. I’d say I value her more than anything. But just being alive on this planet. What a good time can be had by all if we just open the doors of perception! There was a great song in the Fifties: “Open up your heart and let the sun shine in.” That’s about it. Let that sun enter into that heart, feel the rays of the sun.

Of course that’s LSD too, psychedelics. That’s what’s great about psychedelics: you actually feel that sun entering into your body. You can become one with the sun. You are one with the sun. The sun is you. The sun is God. You are God. We are all God. The Earth is God. The Earth is our playground. This is the Garden of Eden, we’ve just forgotten. So, that’ll take care of you. You can end with that. “The Earth is the Garden of Eden, we’ve just forgotten,” said Ray, with a chuckle.

At the conclusion of the interview, Ray turned the recorder off, indicating that he was done talking. He then led me outside to a chicken coop, where he fed his chickens and talked to them like they were little people. I was enamored by his enthusiastic spirit. It was something I’ll never forget.

A note to readers: Bold and uncensored, The Austin Chronicle has been Austin’s independent news source for over 40 years, expressing the community’s political and environmental concerns and supporting its active cultural scene. Now more than ever, we need your support to continue supplying Austin with independent, free press. If real news is important to you, please consider making a donation of $5, $10 or whatever you can afford, to help keep our journalism on stands.

Raoul Hernandez, Aug. 9, 2017

Raoul Hernandez, June 9, 2016

Ray Manzarek, Robby Krieger, Jim Morrison, John Densmore, Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, The Doors, Fats Domino, Chet Baker, Gerry Mulligan, Modesto Briseno, George W. Bush, Dennis Jacobs, Dorothy Manzarek