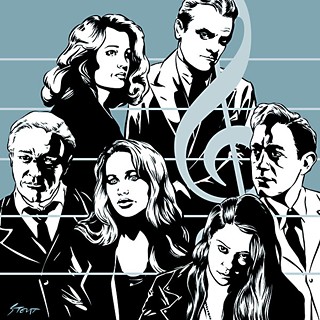

Letters at 3AM: Musicians of Behavior

Actors are musicians of behavior

By Michael Ventura, Fri., May 2, 2014

There is a Celtic proverb that Gioia Timpanelli likes to quote: "The most beautiful music is the music of what happens."

You can follow that sentence down many paths, and what you find will depend on the breadth of how you define beauty. For me, tonight, I think of Timpanelli's sentence because it ignited my first direct connection between music and behavior, that is: behavior as a kind of music.

And I went straight to:

Actors. Actors are musicians of behavior. They play the music of behavior. Actors are their own instruments and each actor is a different instrument, playing the music of behavior on the particular range of that instrument with the particular proficiency of that actor. Any script can be played in many ways and can make many different kinds of behavioral music.

For instance, the character actor Charles Durning, who died on Christmas Eve at the age of 89: Again and again, he was a real toad in an imaginary garden – that is how the poet Marianne Moore might put it, for her poems were "imaginary gardens with real toads in them." Durning is a prime example of an actor who grasped his range of behavior with a powerful understanding, and could play the instrument of himself wonderfully.

Watch the 2004 NCIS episode, "Call of Silence." Durning plays Ernie Yost, a World War II combat veteran who descends into a PTSD breakdown after the death of his wife. The actor was 81 and plainly ailing. As a boy of 21, Durning hit the beach at Normandy on D-Day. In the next months he was wounded three times (meriting three Purple Hearts), and his valor earned him a Silver Star, a Bronze Star, and the French Legion of Honor. Durning never traded on that. When asked to speak of his war experiences he said, "Too many bad memories. I don't want you to see me cry." But in this NCIS episode, Durning was given the shot to speak of the war through his art, and the music of his behavior is profound. It shakes you. And makes you proud.

When Mark Harmon's character, Leroy Jethro Gibbs, says, "This man stood tall in hell," you don't need to know Durning's backstory to feel the truth in the line. Harmon gives the line truth because it is, in fact, true. Most of all, you see Durning finally expressing, in his very presence, what happened. Corny plot devices, silly comic relief, and grotesque commercials can't diminish the power of what Durning gives us. We don't feel it as something arty or cerebral. We feel it as music: the direct force of behavior.

NCIS again, from 2010, the episode titled "Mother's Day." The guest actress was Gena Rowlands, 79 years old, the most original player of her generation, with a breathtaking range. Here she plays a woman who avenges her daughter's death by seducing one of the men responsible and shooting him in cold blood as he's about to propose marriage. She's believable beyond doubt. Corny plot devices and insulting commercials go by unnoticed because what makes the screen glow is Gena Rowlands orchestrating a music of herself, of her behavior, to demonstrate the permanence and potency of deep emotions in those who are deeply alive.

Orchestration: The Canadian actress Tatiana Maslany, a small dark force of nature, plays many roles in the Canadian TV production, Orphan Black: Sarah, Helena, Cassima, Beth, Rachel, a dead German whose name I've forgotten, and several more – often three Maslanys are on screen at once, talking to one another. But you're sucked into the story and you forget that nothing of this scope has been attempted by any actress ever. Maslany speaks to Maslanys, kills a Maslany, watches a Maslany die. A dizzying juggling, not of identities only, but of the very concept of identity.

David Thomson said it: "Why do we go to the cinema, sit in the dark before overwhelming fantasies that appear real? To share in these plastic movements, to change our own lives, to encourage the profound spiritual notion of our flexible identity."

Now that there's Netflix, Hulu, DVDs, Blu-rays, we can pretend we're not sitting in the dark, but our living rooms and bedrooms are as dark as anywhere, and, in those rare moments when we're honest, we know it. In our bedroom or living room – those intimate spaces where we make and/or ruin our lives – we watch the screen and expose ourselves to the profound notion of our flexible identity. Are you who you believe you are? Are you really?

Tatiana Maslany, whom you wouldn't necessarily notice if she passed you on the street, fascinates because she's playing a music you've never heard – a music that, if you step back and consider, challenges your right to say "I."

Bette Davis did the same, but in different pictures over six decades.

So did Alec Guinness, and he did it uncannily. Alec Guinness shows up on the screen and, without saying a word or moving a muscle, he conveys the entire psychology of his role, be it a benighted rural priest in Monsignor Quixote, a master spy in Smiley's People, or a soldier deeply in denial in The Bridge on the River Kwai. Guinness gives you orchestrated character sonatas by merely showing up. How he did that, I wouldn't dare speculate.

Humphrey Bogart did it, too.

So does Jennifer Lawrence. She has only to cast her glance – be it in Winter's Bone, The Hunger Games, or American Hustle – and she transmits a music we have not yet heard: The impression she makes is so open-ended, yet so definite. We know her and we do not. No actress but Greta Garbo has ever done that, and Garbo did it in a different key. Garbo played a music of the Twenties and Thirties; Lawrence plays a key without nomenclature, untied to any time. Perhaps her screen power is that, moment by moment, you feel you understand her – but if you step back a bit you can't tie her down.

Other musicians of behavior perform the way Billie Holiday sang. Holiday had an extremely limited vocal range, but, within that range, she found unexpected shades, tinges, nuances, and grace notes never before heard, to create a profound music that belies the simplicity of her songs. John Wayne, Robert Mitchum, and Audrey Hepburn – they did the same thing onscreen.

And then there are the bravura virtuosos: Marlon Brando, Meryl Streep, Robert De Niro, James Dean, Cate Blanchett, Daniel Day-Lewis, Katharine Hepburn, Helen Mirren, Laurence Olivier – though often, with such actors, we marvel at how well they play rather than the worthiness of their music.

And then there are those who are, as Duke Ellington would say, beyond category, like Montgomery Clift and Marilyn Monroe – they just are. They are their music. And they leave you to deal with that.

Silent cinema was a stark music of behavior, extraordinarily eloquent. The likes of Mabel Normand, Lillian Gish, Harry Carey, and Lon Chaney are mostly forgotten, but the icon of Charles Chaplin's Tramp has been with us for a century, because, as Robert Payne wrote, "Charlie [represented] to such an extraordinary degree the whole human race." Chaplin's is the purest music of behavior imaginable.

In truly great films – I'll reel off the first few that come to mind: Wings of Desire, A Woman Under the Influence, La Strada, The Wild Bunch, His Girl Friday – directors achieve an ensemble behavior of counterpointed performances to create a shared sense of experience and of possibility that exists in only that film and is the signature of its greatness.

I find that is true now less and less in feature films and more and more on television, as in Justified, The Americans, Mad Men, Doctor Who, and Borgen. In the recent Star Trek prequels, an ensemble performance of five decades ago is imitated and re-created – a recognition that it takes several distinct instruments, each played in a precise range, for the Star Trek experience to exist.

And then there is that consummate musician of behavior, James Cagney, who gave the best one-line acting lesson extant: "You walk in, plant yourself squarely on both feet, look the other fella in the eye, and tell the truth."