Page Two: Work and Splendor

Harvey Pekar, 1939-2010

By Louis Black, Fri., July 16, 2010

Not being a morning person, I was less than excited when the only screening of American Splendor – a film based on the comics of Harvey Pekar and the lives of Pekar; his wife, Joyce Brabner; and daughter, Danielle – with seats available at the 2003 Sundance Film Festival was at 8am. It was Chronicle Film Editor Marge Baumgarten who opened that door. Now, if I've been up all night watching movies, an 8am screening is fine; I'm usually coming into my second wind at that point. This one was not the tail-end of an all-nighter but found me fresh from sleep in cold, snow-covered Park City, Utah.

Back in my dark ages, the first decade or so of the Chronicle, it was Steve Fore who turned us all on to the great American Splendor comic. Fore, who was a fellow film graduate student in the Radio-Television-Film Department at the University of Texas as well as a CinemaTexas film-program note writer back then, now teaches about film in Hong Kong.

Reading a single issue of American Splendor was more than enough to cause addiction.

I hesitate to credit Harvey Pekar with being the first to use comic books to portray the ordinary and often mundane lives of ordinary and often mundane people, but he is without doubt the most influential. Not that Harvey's work lacks fascinating characters or creative stories, but it is devoid of superheroes, science fiction, historical depictions (for the most part), accelerated melodrama, and hysterical emphasis. Instead the books are autobiographical; they're about Harvey Pekar: living in Cleveland, Ohio: husband of Joyce Brabner, father of Danielle, employed as a file clerk at the Cleveland VA hospital. In American Splendor's wake have come dozens if not hundreds of mimetic comics – essentially a full, expansive genre.

I've been trying to remember how we first got to know Pekar here at the Chronicle. More on that later.

A hipster and fanatical jazz collector, Pekar was an intelligent literary and music critic and historian interested in the more obscure American avant-garde writers, as well as in much of the history of jazz, the blues, and popular music. By far his best-known and most important work was in comic book stories, but he also wrote essays and reviews.

Comic art legend Robert Crumb, his friend since 1962, has written, "Harvey was the first person I met who I thot was a genuine 'Hipster.'" Crumb goes on, "and he was seething, intense, burning up, always moving, pacing, jumping around. ...

"Yeah, Harvey is an ego-maniac; a classic case ... A driven, compulsive mad Jew ... Watching him eat – he eats faster than anyone I've ever seen, shoveling it in as if someone had a gun to his head and was threatening to kill him if he didn't get it all down in ten seconds."

A brilliant observer of mundane human actions and minute details of ordinary life, most importantly Pekar was a nearly unparalleled, world-class grouch, an irritated and irritating malcontent, and one of the great unrepentant curmudgeons of all time.

Charles Bukowski (impossibly hip but not one of my favorites) has a wonderful poem about what really drives a person to madness is when a shoelace tears apart. This is the world Pekar explores. He writes about the daily annoyances of being a file clerk, getting stuck in line at the grocery behind an overly obsessed customer, not getting the doughnuts he wants, a friend visiting and overstaying his welcome, annoying drivers, the almost unbearable existentialism of some simple errands, and all different manner of rude, overbearing people.

In 1976, he began self-publishing American Splendor, featuring his autobiographical comic book stories. Pekar only wrote comic books; he got others to illustrate them. Over time, any number of superb comic book artists worked for Harvey, illustrating his stories while often enduring his nagging phone calls.

Pekar has been compared to Theodore Dreiser, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Jack Kerouac, and Lenny Bruce. Whereas he certainly belongs in their company, such comparisons fail miserably because, just like those others, Harvey Pekar was a completely original artist. In the comic book introduction to one of his anthologies he offers some insights into his world. In one panel, the caption reads, "I think if you feel rotten most of the time by a certain age, you're always gonna feel lousy – your glass is always gonna be half empty." In the panel is an illustration of Harvey saying, "I don't have it worse than a lot of people but I pity myself more."

The one-page strip ends with Harvey observing, "Anyway, I look at it this way – anything that doesn't kill me could be the basis of one of my stories."

Now, if all Pekar did in his work was complain, while also exploring the more obscure nooks and crannies of American culture, there would be little reason to celebrate him. It is in that detailing of the mundane, annoying, and frustrating that Pekar brings an extraordinary energy, a skill at storytelling, and a brilliantly idiosyncratic sense of humor to his work. His tone is both self-deprecating and royally pissed off. Reading it ends up being a magnificent, exhilarating, sometimes hilarious, but always life-affirming experience.

In many circles, over time, American Splendor came to be a highly regarded and praised publication. Still, Harvey's greatest and most public notoriety was when he was booked on David Letterman's NBC show, as an anthology of his work had been published. Pekar was all over Letterman, who had no idea at all of what to make of him. There were another seven or so guest appearances on Late Night, until Harvey got himself banned when he opened his shirt to reveal an anti-GE slogan after that multinational conglomerate had purchased NBC.

It was during one of Harvey's early Letterman appearances that one of my favorite illustrative moments of contemporary culture occurred. Harvey was talking to Dave about how, because he had no money, he was going to have to work as a filing clerk until he was eligible for his retirement benefits. Clearly, Letterman didn't believe him, pointing out that Pekar had published this book. It seemed as though Letterman couldn't believe that a well-known cultural figure with a book out from a mainstream publisher could be broke.

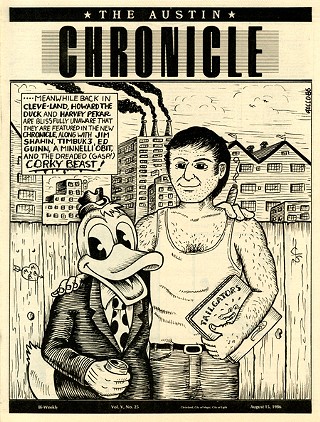

In the history of the Chronicle, certainly for the first two decades, we almost never put anyone on the cover who wasn't related to Austin in some direct way. There were exceptions: For film series, we had Sam Peckinpah and Robert Thom on the cover, and I know that Frank Zappa and Duke Ellington were each on the cover once. When it comes to Cleveland's Harvey Pekar, I'm trying to remember if we had him on the cover only twice, or was it three times?

After the first cover appearance, Harvey got in touch with us. He would call looking for work, always out hustling to make money. Talking to Harvey on the phone mostly involved listening, as in a soft but unending voice, he almost breathlessly offered endlessly run-on sentences, a fantastic verbal poetry with a Beat argot and rhythm detailing the latest annoying details of his life. "I just can't get on the phone any more, Joyce is on it all the time, at least all during the day so I can't get or make calls, man it is driving me crazy. Who knows who's trying to call me? And Joyce, Joyce, now she's taking my old clothes to make into Harvey Pekar dolls that she's selling and, man, do you have any work for me, anything I can do, we need the money ...."

Eventually Harvey and Joyce visited Austin, which led to our becoming actual friends. They were both smart, articulate, and entertaining. It was fun hanging out with them.

Harvey chronicled his life's most petty as well as important details, including meeting and marrying Joyce Brabner, adopting a daughter, his bout with cancer, and his experiences when a movie based on his work was finally made.

There were many years of extended phone calls between Harvey and myself or other members of the Chronicle staff. Very occasionally, we'd get together socially. Music Editor Raoul Hernandez became Harvey's main Chronicle contact for many years. Earlier today, he sent me an e-mail: "not three weeks ago Agnes and I were having milkshakes with Harvey just around the corner from his brownstone in Cleveland Heights. then we hit a record store together two doors down from the restaurant. hell, he was the LEAD of my Crossroads feature two weeks ago. it was the first time we'd met after an inadvertent estrangement. i'm kinda heartbroken. poor Harvey."

I don't know. I think I love Harvey and Joyce. I know I love their work.

There had been any number of attempts to capture Pekar's world on film, but all had come to nothing. At one point, my friend Jonathan Demme contemplated making an American Splendor film but couldn't raise the money at the time. As always Harvey complained: "Demme? Demme? He's talking about having some kid waiting in line at a grocery cashier wearing headphones but Demme wants him to be listening to loud punk music! Punk music! I don't know anything about it and I'm not interested. That's not my trip at all."

Producer Ted Hope, then working for Good Machine, initiated an American Splendor film, worked out a deal with Joyce, and hired the husband-and-wife team of Shari Springer Berman and Bob Pulcini to write and direct (Harvey had done a draft of the script). Paul Giamatti and Harvey Pekar played Harvey; Hope Davis and Joyce Brabner played Joyce.

American Splendor is a brilliant, innovative film that remarkably captures both Pekar's world and the many textures of his storytelling. Watching it at that ungodly early hour made no difference. After the screening, the filmmakers, Harvey, and Joyce did a Q&A. After that was over, Marge and I went up to say hello to them. Immediately after saying hello and sharing her happiness to see us, Joyce pushed on to: "Do you have any work for Harvey? He needs the work, and we need the money!"

We next said hello to Harvey, me not realizing it would be the last time I'd ever see him. Like Joyce, he almost immediately launched into: "You got any work for me? We need the money."

For more about Harvey Pekar's writing for the Chronicle, see "Off the Record," Music, and his online archive at austinchronicle.com/harveypekar.