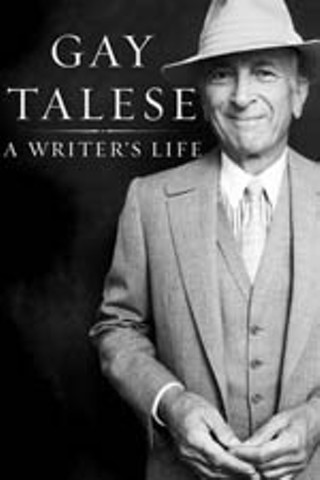

Book Review: Readings

Gay Talese

Reviewed by Josh Rosenblatt, Fri., April 28, 2006

A Writer's Life

by Gay Talese

Knopf, 448 pp., $26

OK, so you're Gay Talese, one of the most influential journalists of the past half century – no less an expert than Tom Wolfe once called you the "founder of the New Journalism" – and you're a bestselling author, and you've written world-famous profiles of some of the most world-famous men of the 20th century, from Frank Sinatra to Peter O'Toole, from Joe Louis to Joe DiMaggio, working for no-account rags like The New Yorker and The New York Times and Esquire, standing for years on sidelines or against walls or in shadows, taking notes, practicing the "fine art of hanging around," as you call it – you were an observer on that bridge in Selma, Ala., where John Lewis and his freedom marchers met the billy clubs of sheriff Jim Clark and his thugs – and you've made millions writing books about mobsters and bridge-builders and newspaper men, and you get the big advances and you get a huge advance to write your next book, and your publisher is waiting and the walls are closing in, and after years' worth of false starts and flat rejections, you finally light on an idea worth the name: a writer's memoir. You'll set down for the record all those false starts and encroaching walls, all the waiting and the missteps, the failures, the repeated refusals, and the odd successes and broadcast them as the sum of parts that have added up to your life as a journalist: the closest you'll ever get to an autobiography, most likely, because, for you, a writer's life and his work are inextricably interwoven."I had never given much thought to who I was," you admit. "I had always defined myself through my work, which was always about other people."

So, instead of beginning this story at your beginning – with your birth to Italian immigrant parents in 1932 in the small island town of Ocean City, N.J., where you passed all those impressionable hours in your father's tailoring shop, quietly observing and listening to the stories of his clients, one of whom was former New York Times editorial page editor Garet Garrett, whose "metropolitan splendor" and journalistic acumen you looked up to and coveted as the personification of the life you, a high school newspaperman yourself, wished to inhabit – you start your story with another person's. In this case, that of Liu Ying, an otherwise forgettable and forgotten midfielder on the Chinese women's national soccer team whose errant penalty kick in the 1999 World Cup finals opened the door for a U.S. victory and the iconic disrobing of Brandi Chastain, whose black sports bra was elevated overnight to a garment of mythic status, a Shroud of Turin for the Title IX faithful.

But that seems appropriate. Fifty years a journalist and your writer's life begins with someone else's life entirely.

Someone else's failure, more to the point. Watching the end of that game, you weren't interested in its conquering hero or her choice in underwear. You wanted to know about the conquered Liu Ying, alone in some locker room, who in less time than it would take to type this sentence became a disappointment to a billion people. Because those are the people you write about: the losers, the forgotten and forgettable guys behind the guys behind the story; and the accomplished and famous men after their fame has receded and they've been left alone to negotiate the ever-blurring line between adoration and indifference.

And somewhere in those 50 years your life got tied up in theirs, and their failures were mirrored in your own.

So you keep writing, and while what you write looks for all the world like other people, it might just, in fact, be all you.

Either way, the process repeats itself, even at 74, slowly and arduously and meticulously. Just you and a yellow legal pad, alone again, writing like "a tailor," you say, like your father, "stitching, stitching, stitching."