Some Unspeakable Beauty

Don't call It magic realism: Josephine Sacabo's photography and Juan Rulfo's "Pedro Páramo" make a powerful pair

By Belinda Acosta, Fri., Nov. 8, 2002

Josephine Sacabo knew early on that she was an artist. However, like many artists, it took her a while to figure out exactly how to realize that calling. As a member of a large, landowning family of cattle raisers from Laredo, "artistic pursuits were virtually unheard of, so it was never clear that being an artist was what I was about," Sacabo says. "I was definitely different, and [it's] probably safe to say I was a confusing and sometimes trying child. But my mother championed me even when she couldn't quite understand what it was I was seeking and why I was so often at odds with my world."

As a girl, Sacabo aspired to be a great poetess. That idea subsided (though she eventually studied English literature at Bard College), and the "Elvis Presley heads" she drew for her family's amusement turned out to be the extent of that portfolio. So, she turned to acting. She performed with the Bird in Hand Theatre Company, an experimental theatre group that she ran with her playwright husband in London, then New York, and finally New Orleans. But then came motherhood. She wanted to find something that would suit a busy mother's schedule, which is when she came across a camera left by a former resident in the house she and her husband were renting in the French countryside. She asked a photographer friend to show her how to use it, and when her first images bloomed before her in the darkroom, her reaction was "Wow, this is fabulous!" She'd found the voice to answer her calling.

That was more than 20 years ago. Now, viewers all over the world have been saying "wow" to Sacabo's photographs. While New Orleans is now home, Sacabo was recently in San Marcos for the opening of her newest one-woman show, "The Unreachable World of Susana San Juan -- Homage to Juan Rulfo's Pedro Páramo" at the Wittliff Gallery of Southwestern & Mexican Photography. Photographs from the exhibit are also included in a new edition of Rulfo's novel, Pedro Páramo, translated by Margaret Sayers Peden, published by the University of Texas Press.

Perhaps it's luck, kismet, or destiny that brought Sacabo to photography, but it's much more than luck that makes Sacabo a world-class photographer. Through her lens, negatives over negative prints, oil washes, burning, and other techniques, she captures what photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson (one of Sacabo's major influences) calls the "decisive moment."

Or not. According to the down-to-earth Sacabo, photography is not always under her complete control. Temperamental film, cameras that don't operate as expected, light that plays one way before the eyes and another when refracted through the lens, and other factors can perplex even the most accomplished photographer.

"They lie," Sacabo says with a laugh at photographers who claim to have every element of the process under control. "If I'm lucky, I'll do the photography well." Because her work is so subjective, when "mistakes happen, I can always use it somewhere else. I am not into literal, sharply defined images. I go instead for overall mood at expense of the details."

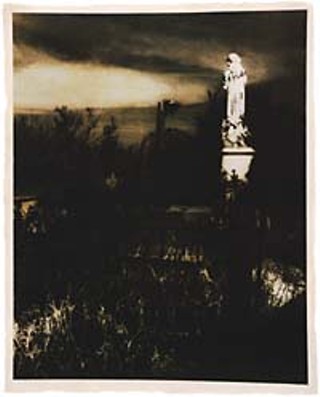

This explains part of the unspeakable beauty of Sacabo's photos. Not that they can't be described: Moody, doleful, luminous, and introspective are useful words. But please don't use the term "magic realism" to describe her work. "I can't stand it when they say that about me," she says. "It's totally not applicable."

Sacabo's current exhibit has most likely been described as magic realism because Rulfo's Pedro Páramo is cited as influential to the literati who enjoyed great success during the Latin American literary boom of the late Sixties and Seventies, when magic realism made its first impression. Today, scholars debate its meaning, and the term has much in common with how the visual art concept "surreal" has been corrupted to mean anything that is strange or weird. Weird, that is, from a Western perspective. Its harshest critics denounce magic realism as a means of cultural subordination.

Magic realism is about things that are tangible, suggested Fernando Curiel, a Rulfo scholar who spoke at Sacabo's Wittliff opening. Rulfo's world and the world Sacabo reveals in her stunning photographs reach a different kind of reality. She photographs the glint of those small, supposedly insignificant moments to reveal a larger truth -- reality's second skin. In her work, the small gesture of a street beggar is imbued with grace in La Pordiosera (The Beggarwoman). The ecstasy of the faithful wells in a flight of birds above a chapel in El Vuelo (The Flight). A milky white angel brings comfort as it guards the remains of the forgotten in Cementerio I (Cemetery).

Viewers are sure to create their own interpretations of what they see in Sacabo's work because, as Curiel suggested, "there is an unyielding openness inherent in true [art]. W.H. Auden wisely said that having finished reading a great book, the reader goes on writing it in his own way, for now its characters and their virtuality wholly belong to them."

If Sacabo's photos "rewrite" Rulfo's Pedro Páramo, viewers of her work will inevitably do the same in their own, imaginative universe. Seen in this way, all great art is magic.

As a woman who fell in love with language at an early age, Sacabo recognizes the links between her work and the written word, both figuratively and literally.

"Poetry and photography are both a task of distillation, a way to bring the complexities of the world down to one perfect image," she says. More explicitly, she has used poetry and literature as a point of departure and inspiration. Her 1991 series of photographs, "Une Femme Habitée" ("The Inhabited Woman"), were created in response to the 1930s poetry of Chilean poet Vincente Huidobro. Other writers who have inspired her include Rilke, Baudelaire, Pedro Salinas, and, most recently, Rulfo.

Ah, Juan Rulfo, Mexico's greatest 20th-century writer according to many. His one and only novel, Pedro Páramo (1955) is considered a cornerstone of Mexican literature and a classic among Latin American letters. Published when Mexico was feeling the aftereffects of a tumultuous revolution, the book is praised for "capturing the disquieting presence of a dying but not quite dead traditional Mexico ... a lingering reality no longer present, not yet past," according to Danny J. Anderson in his essay, "The Ghosts of Comala: Haunted Meaning in Pedro Páramo."

The slim novel begins with Juan Preciado keeping a promise to his dying mother by traveling to her beloved village of Comala in search of his birth father, Pedro Páramo. But when Juan finds the vestiges of the once vibrant Comala, he enters into a world where wandering souls yearn to tell their stories, and the living and the dead are sometimes indistinguishable. Like Juan, the reader finds themselves baffled by the confluence of voices, time shifts, and perspectives. Still, Rulfo's images and deeply realized undercurrent of longing are hypnotic.

Intertwined with Juan's journey are the details of Pedro Páramo's life, as is that of Susana San Juan, the woman he desires but can never possess. It is Susana's story that took Sacabo by the throat.

"Susana ... is a woman forced to take refuge in madness as a means of protecting her inner world from the ravages of the forces around her: a cruel and tyrannical patriarchy, a church that offers no redemption, the senseless violence of revolution, and death itself," Sacabo says. "These photographs are my attempt to depict this world as seen through the eyes of its tragic heroine. It is my homage ... to all Susana San Juans everywhere who will not be possessed."

Interestingly, Sacabo did not start out creating works specifically for Pedro Páramo. Like Rulfo (also an accomplished photographer), she found herself lured to Mexico's lost villages. Driven by an idea for a project that was ill defined but percolating, she and a friend traveled to the Mexican village Guerrero Viejo. She'd heard of its breathtaking ambience, and when she arrived, she was not disappointed. She began taking pictures of its sad beauty, for what, she wasn't sure. When her friend told her mother of her excursion with Sacabo, "her mother said, 'It sounds like you're doing Pedro Páramo.'" That prompted Sacabo to read the book, and as that ever-present luck, kismet, or destiny would have it, the book gave direction to her project. In the process, she was able to pay tribute to a woman with whom she felt a strong kinship.

"I could have been Susana San Juan had I been born 50 years earlier," Sacabo says. She imagines San Juan as the "madwoman in the attic," an unfulfilled artist perhaps, who sought refuge in her madness when there was no other reality available to her. But Susana San Juan is not powerless. Thanks to Rulfo, she transcended the page to possess Sacabo. Or perhaps it's more appropriate to say that Susana allowed Sacabo to possess her for a time, to create her arresting photographs and give form to Susana San Juan's strong spirit. Whatever the case, it's clear that the union between the two women was not luck, but destiny. ![]()