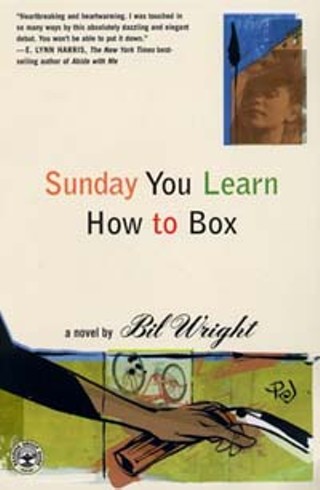

Sunday You Learn How to Box

Reviewed by Dan Oko, Fri., May 12, 2000

Sunday You Learn How to Box

by Bil WrightScribner, 218 pp., $12 (paper)

Despite the title of Bil Wright's debut novel and the fact that this urban tale kicks off with the alarming death of the protagonist's evil stepfather, the book's violence is primarily emotional. Sunday You Learn How to Box is the story of Louis Bowman, a young black man growing up in the projects just outside of New York City during the late Sixties and early Seventies. Despite this time frame, however, the novel is no more a civil rights allegory than it is a pugilist's coming-of-age; rather, young Louis must learn to deal with his alcoholic mother's crushing over-attention and his own burgeoning realization that he is gay. Given the backdrop and the era, homosexuality is no simple burden for Louis, who appears reasonably aware that his behavior is not what's expected of a young man on the verge of adulthood. When he receives a bike as a Christmas present, Louis finds himself at a loss. He doesn't really want the gift -- and we soon discover why. The afternoon Louis first takes the bike down into the courtyard, he's victimized by neighborhood bullies, who have already identified our hero as a sissy. His stepfather, Ben, who has been enlisted to help the boy learn to ride, adds insult to injury by allowing the other children to play with Louis' shiny new toy. By contrast, when Louis encounters the soul singer Jackie Wilson on television, he tells us: "Jackie Wilson was the prettiest black man I'd ever seen, with high, jutting cheekbones and skin that looked like powdered satin." When Louis finds himself confronted by Ray Anthony Robinson, a mysterious neighbor with a reputation for so-called craziness, their emotional kinship galvanizes Louis' emerging sense of identity and sexuality. In the meantime, the painful (though barely portrayed) boxing lessons of the book's title, doled out hatefully by Louis' stepfather Ben, allow the boy to assert himself when he's attacked by a stranger who has sensed his curiosity about sex and seeks to take advantage of it. In the end, the novel shapes up as a brief yet engaging meander through the trials of this singular adolescent experience. Wright has a keen eye for detail and employs a plainspoken, honest voice that more than holds the reader's attention. Still, he would have been wise to delve into the nuances of the relationships that drive the book instead of relying solely on the perceptions of Louis, a recognizable character in a tough but not particularly original predicament.