Telling Stories

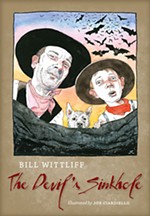

Wittliff seeks the "yes" in his debut novel, The Devil's Backbone

By Joe O'Connell, Fri., Dec. 5, 2014

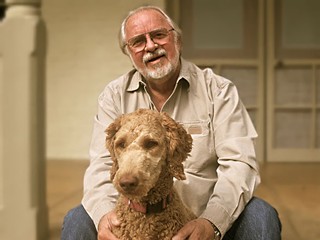

To meet Bill Wittliff in his Downtown Austin office is to meet Texas. O. Henry used to live here, and Bud Shrake came over to write. John Graves' paddle from Goodbye to a River hangs from a wall. Upstairs is the desk of Wittliff's former teacher J. Frank Dobie. Its yard sale purchase, along with 30 or so boxes of Dobie papers, led to the Wittliff Collections of Southwest literature and photography at Texas State University. Over there is a lush Wittliff-shot photograph of Robert Duvall on the set of the Lonesome Dove TV miniseries that Wittliff penned along with the very Texas screenplays of Honeysuckle Rose, Raggedy Man, and the recent (though 39 years in the making) A Night in Old Mexico. Across the room is Wittliff's portrait of Willie Nelson. Through Encino Press, founded with wife Sally in the Sixties, he's created important Texas books. Now he's written one, a novel called The Devil's Backbone that is both beautiful to look at (credit 25 images inside and a color cover drawn by Jack Unruh) and a joy to read (see sidebar, at right). A sequel is in the works. With his poodle Chica listening in, Wittliff spoke about the new chapter in his artistic life.

Austin Chronicle: Tell me how this story came about.

Bill Wittliff: I went to my grandfather and asked him to write his memoirs. He had not gotten out of the second grade, but he went down to the drug store and bought an old typewriter. With one finger of one hand, he typed his memoirs. But he didn't know how the typewriter worked, so he would start long before he got to the paper and he would quit typing long after it was off the paper. What I got was just the middle but not the beginning and the end, which was really a great thing because I then went and interviewed him. He would tell me things he simply would not put on paper.

Later, I asked my mom to write her memoirs. She also didn't have a big education but was an exceedingly bright and industrious woman. For two years, she wrote on Big Chief tablets. I thought I'd put these two together and make a unified narrative. I started doing that and was having a lot of fun with it. But I hit a place where I knew my mother had not told the whole story. It stopped me dead in my tracks. By this time, both my grandfather and my mother were gone. I could've made up some stuff to fill in the blanks, but it didn't feel right. I left it. A couple of years after that, a cousin called and asked me how it was going. I told her Mother didn't tell the whole story. She said, "Oh, I know that story." Her mama, my aunt, had told her. She told it to me, and I knew why Mother had not told it, and I knew why I couldn't tell it. There were relatives still alive and it would be very hurtful to them. But I got to thinking: They got to live those lives once; now I get to live them. I started over and decided their stories would be an inspiration for something new. It just took off for me.

I made a deal: Every time a character would knock on the door and want to come in, I'd say there's only one sin you can commit: to be boring. And if you are boring, the next character through the door is going to shoot you, hang you, or run you out of town.

AC: How was this a change from screenwriting?

BW: In screenwriting, you are dealing with a finite amount of space and time. It's very difficult to give background, thought patterns, and all that. In a novel, you can do anything you want. But I never felt constricted anyway. I was here [in Texas]. I never lived out there [Los Angeles]. God knows I had enough battles along the way with "You can't say that" and all the business of making a movie.

AC: You made an interesting narrative choice with an unnamed character relating the stories of "Papa," who's actually a young boy.

BW: This is the way it came, and as long as it felt good to me, as long as it had a life of its own, I went with it. I didn't care what that life was either. I didn't try to censor the shimmery people or ghosts or whatever. I didn't know until the very end what Papa was going to find at the Devil's Backbone. I didn't know it was the Devil's Backbone. The first time it shows up is in one of his dreams. I figure if you have an itch, you have the ability to scratch it. I wanted to write these stories in book form. When I say "these stories," it's not to suggest I knew what these stories were. But I had an itch to write a book. This is how I scratched that itch.

AC: How did you come to be a storyteller?

BW: My father was a terrible drunk. My mother took my brother and me and left him because she was afraid he was going to drag us down. He simply could not walk past a bottle of beer. Mother got a job running the telephone office in Gregory, Texas, during World War II. The whole house was about the size of this room. Mother ran the switchboard and we lived there. She got $5 more a month to be the janitor. She was determined that my brother and I get real educations. My brother went on to get a Ph.D. in molecular biology from the University of Texas. I got a degree simply because my mother wanted me to. At that time and in those places, there was a certain stigma attached to any woman who was divorced. The assumption was there was something wrong with her, not the man. All those towns were father-son oriented – hunting, fishing. If you didn't have a father, you were on the edge of the community. We moved to Edna and again lived in a telephone office. There it was even more pronounced. There was a family that lived down the street and around the corner, the Calloways. Tom Calloway was a terrific storyteller. Every evening after supper, he would sit on his side porch and tell stories. Neighbors would come. He'd tell a story and somebody else would tell a story. Two kinds of people belonged in places I lived: storytellers and cowboys.

Down the road from us was the Westhoff lumber yard. Mr. Gus Westhoff would get me boards, get me nails, and tell stories. He told me the story of the Wild Woman of the Navidad, about an escaped slave woman. It totally fascinated me. The ranchers would try to find her but found only her tracks and the tracks of a child with her. Then the tracks of the child disappeared. I worried about what happened to that child. Years and years later, my aunt sent me a copy of J. Frank Dobie's I'll Tell You a Tale. The third or fourth story was "The Wild Woman of the Navidad." It hit me that it was possible to make books from your own piece of ground. My second volume (of the Papa stories) has a lot of the Wild Woman of the Navidad in it from both the stories I heard from Mr. Westhoff and my reinvention of them.

AC: Your stories talk a lot about the creation of family.

BW: That's in all my stuff. That's me trying to fill a void I felt as a child given where I came from. Everybody has a whip to drive their ox. I think I've been very, very blessed to come up in a situation that was very close to the bone.

AC: Race plays a big role in this book, too.

BW: I'm absolutely sure my attitudes about race come from Mr. Westhoff telling me the story of the Wild Woman of the Navidad. I identified with her and her lost child. That made me so sympathetic to anyone who was off to the side. There's a quote from E.M. Forster: "How do I know what I think until I see what I say?" It's not what I'm telling it; it's what it's telling me. That is a huge thing. I always tried to stay ignorant. I don't type. Later I understood that some part of me wanted to stay ignorant. I succeeded. When I write, I write in pen and ink, and I see the actual ink going into the paper. It can throw me in a trance where I can get out of the way. The truth is, I think everybody knows everything anyway. What artists do and writers do, poets do, songwriters do, and musicians do is present it in a way that people remember. That's why a great piece of writing, art, poetry, whatever, never tells you anything. But your first response to the greatness is a yes. Yes! Because it's already in them. Later they can think about it, intellectualize on it. But the first response, always, to greatness in the arts is "yes!"

The Wittliff Collections at Texas State University will hold a celebration of The Devil's Backbone with author Bill Wittliff and illustrator Jack Unruh on Sunday, Dec. 7, 2pm, in the Alkek Library on the university campus in San Marcos. Admission is free and open to the public. Attendees are requested to RSVP to thewittliffcollections@txstate.edu for easy parking information and other details.