A Lie of the Mind

While maybe not Sam Shepard's best, the play has worthwhile material to chew on

Reviewed by Adam Roberts, Fri., Nov. 18, 2011

A Lie of the Mind

Mary Moody Northen Theatre, 3001 S. Congress, 448-8484Through Nov. 20

Running time: 2 hr., 30 min.

Paranoia abounds in A Lie of the Mind, Sam Shepard's surrealistic tale of dysfunctional family life exposed for all to witness at the Mary Moody Northen Theatre. The topic is nothing new for Shepard, whose work is often concerned with that place called home and the tribulations that can rip families to shreds. There's good reason for that paranoia, too: In the first moments of the play we are introduced to Jake, who has beaten his wife, Beth, to such a degree that he believes her to be dead. But in truth she is alive, riddled with brain damage and unable to speak coherently. These introductions to the play's primary characters presuppose an evening heavy with intense drama, promising to leave the observer drained of emotion. And it does. The surprise, however, is the remarkably consistent thread of comedy Shepard masterfully weaves throughout the lengthy piece (there are two intermissions). This oftentimes peculiar crackle of the seriocomic is what gives A Lie of the Mind its thought-provoking resonance and leaves one with a startlingly unsettled sense of closure at evening's end.

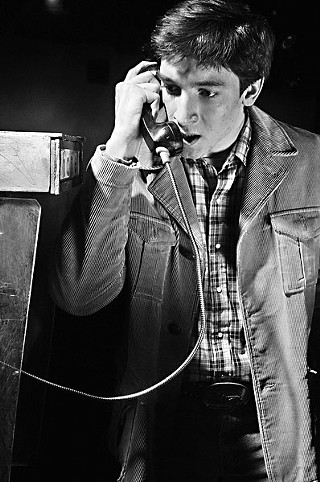

To be honest, though, it's not my favorite play. Shepard's monologues at times grow tedious as they labor on, giving one the sense that the same content could have been conveyed just as convincingly in half the time. Once the point has been made (and made again), it becomes easy to lose attention. Moreover, the work's constant shifting between the natural and the absurd – which can represent a masterstroke of art when the genres are mixed seamlessly and convincingly – evokes a confused haziness, leaving me with a sense that the play is not sure of what it wants to be. Nonetheless, the performances in this MMNT production are strong on the whole. Meredith Montgomery's Beth is especially well executed as she searches with a frustrated rigor for the words and steps that now escape her. Montgomery's transformation from fully bandaged invalid into the young woman we see at the end of the play, walking slowly and with some of her faculties for communication reclaimed, provides an especially impressive portrait of character development. Jon Richardson, as Jake's brother Frankie, likewise exhibits a strong sense of comedic physicality.

As is typical of Shepard's plays, A Lie of the Mind offers an intricate psychological prism. We're left with many questions, some of which the playwright has addressed from his own position, but many more of which are left intentionally unanswered. Those who attend will be challenged; catharsis from some aspect of one or more of the characters will likely be experienced. The potential exists to laugh and to cry – probably both at once. Director Jared J. Stein offers his audience an interpretation that glimpses into the mind of one of America's foremost voices of the theatre, and whether or not it represents the best of Shepard, it's worthwhile material to chew on.