Texas in Bold, Dark Strokes

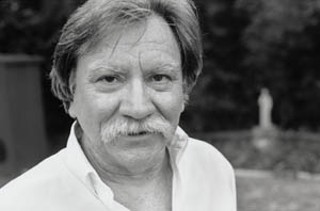

Jack Jackson, 1941-2006

By Robert Faires, Fri., June 16, 2006

When you're talking about Jack Jackson, it all comes down to history. If this wildly talented artist and scholar wasn't studying it, researching it, and re-presenting it in painstakingly drawn graphic novels and other texts, he was making it himself, launching what came to be known as underground comix with a pamphlet he produced right here in Austin. And sometimes he wound up doing both at once, as with Comanche Moon, his version of the life of Comanche chief Quanah Parker, which told his story from the Indian point of view for the first time. By the time he passed into history himself last week, Jackson had challenged and done much to change the way we look at comics and at the past, particularly Texas' past.

View a larger image

Jackson was born in tiny Pandora, Tex., (pop. 200) and grew up in nearby Stockdale, due south of Seguin. By the time he came along in May 1941, his family had already been in the state for a century, his great-great-grandfather having settled in Texas while it was still a republic. As a boy, Jackson was fascinated with Native Americans, seeking out stories of Indian life and whatever remnants of their culture – mostly arrowheads – could be found in the countryside around him. But for a while that interest was sublimated to more practical concerns, and when the time came for Jackson to go to college, he opted to major in the eminently practical field of accounting.

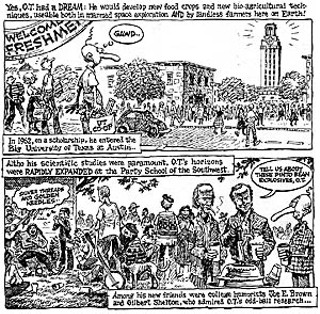

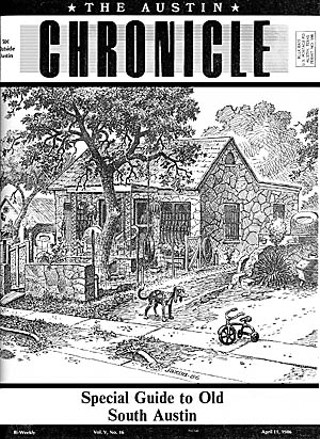

It was not to last long. Jackson landed in Austin at the dawn of the Sixties and fell in with the irreverent crew at the Texas Ranger humor magazine, where he became friends with another budding cartoonist named Gilbert Shelton. At the Ranger, Jackson and his pals tested the limits of personal expression – until they were forced out over what he called "a petty censorship violation." (Shelton has said that contributors were sneaking obscenities into the magazine's illustrations and text.) Jackson found other outlets for his talents: Shelton's short-lived rag THE Austin Iconoclastic, to which Jackson contributed a regular feature, "Austin's Monuments to Bad Taste," and his own satirical comic, God Nose, which he peddled on the Drag. This 1964 self-published effort by Jaxon – a name adopted to protect his day job – is now generally accepted as the first underground comic. Two years later, he, like a lot of young Texans, headed to San Francisco to help bring psychedelia into full flower.

Out in Haight-Ashbury, Jackson began creating posters for Avalon Ballroom concerts as an art director with Family Dog, the legendary music promotion entity founded by Texas transplant (and UT dropout) Chet Helms. In 1969, Jackson and three other Lone Star expats – Gilbert Shelton, Fred Todd, and Dave Moriaty – chipped in $75 apiece for a down payment on a $1,000 offset printing press and started their own little print shop. They christened it Rip Off Press, and it became one of the seminal publishers of underground comix, from Shelton's Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers to R. Crumb's Comix and Stories to Jaxon's God Nose.

While in San Francisco, Jackson was commissioned to draw a coloring book featuring Indian chiefs, a project that revived his childhood interest in Indians and inspired him to revisit their stories. By the time he returned to his home state in the Seventies, he'd begun to produce the kind of illustrated tales of Native American history for which he has become famous. His graphic biography of Quanah Parker, published in 1979 under the title Comanche Moon, started Jackson in a new direction: telling true tales of Texas in graphic-novel form.

View a larger image

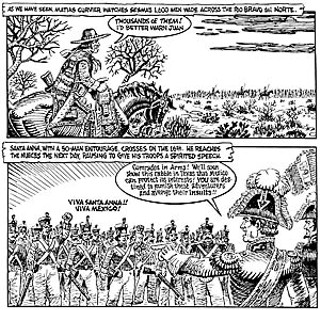

While such stories may seem a far cry from the head-shop humor of comix, Jackson saw his time in the underground as key to the historical work he sought to make. As he told Jesse Sublett in a 1997 interview for this paper, "I was in a position to do what Harvey Kurtzman did with the EC war books, telling true stories. Except now, with the freedom that came from the underground, you could do it with no holds barred. You got a massacre scene, hey, you're free to show it. You know, all the real violent stuff, the racism that went on, how the West was won; all of a sudden you're free to deal with these themes."

Jackson set out to relate sagas of Texas that had been hidden or whitewashed: the tale of Juan Seguin and other Mexican-American heroes of the Texas revolution (Los Tejanos); of the Karankawa tribe's massacre of the Spaniards (God's Bosom); of the Sand Creek Massacre (Nits Make Lice); of Sam Houston's time among the natives (Indian Lover: Sam Houston & the Cherokees); of the way the Mexicans remember the Alamo (The Alamo: An Epic Told From Both Sides). The results are gripping stories, meticulously researched and rendered, but often brutal and, given Jackson's penchant for black-and-white illustration, stark. As Sublett himself characterized it in that interview, this is "Texas in bold, dark strokes."

View a larger image

In one instance, that led to controversy and a deep rift between Jackson and the Chronicle. Jackson had been an illustrator for the paper in its early years, and his work had been championed by several writers in it. But when Michael Ventura reviewed Lost Cause, Jackson's 1997 graphic novel about gunslinger John Wesley Hardin, he accused Jackson of being a racist. Jackson sought to respond to the charge with a long rebuttal, but editor Louis Black declined to run it. When a furious and frustrated Jackson called fellow Austin cartoonist Mack White, White suggested he put the rebuttal on the Internet. White himself retyped the 10-page letter onto an e-mail discussion list, where comics fans across the country learned about it. That led to Jackson's being interviewed about the matter in The Comics Journal, a national publication.

Despite their attention to detail, Jackson's graphic histories never really garnered the respect of academics. They could still be dismissed as comics, kid stuff. But in 1986, Jackson produced a noncomics history, Los Mesteños: Spanish Ranching in Texas, which was so well-received – it won "every award given," Jackson used to say – that Jackson was not only welcomed into the brotherhood of scholars, he was made a Lifetime Fellow of the Texas State Historical Association and inducted into the Texas Institute of Letters. He went on to write more scholarly tomes on Texas rivers and historical cartography and contributed drawings and maps to numerous academic histories.

View a larger image

He succeeded in all this despite a degenerative muscular condition afflicting his hands. According to one fellow artist, it made his hands like claws. But, says Rick Veitch, "Unfazed, he would push a brush into his claw and just paint like Rembrandt."

Jackson was in his hometown last Thursday when he died. He was found at the Pleasant Valley Cemetery. Both his parents were buried there, and Jackson was laid to rest there on Monday, June 12. A memorial service will be held Saturday, June 17, 11am, at Hyde Park Christian Church, 610 E. 45th. Jackson is survived by his wife, Tina, and son, Sam.

View a larger image

In The Comics Journal interview sparked by the Lost Cause controversy, Jack Jackson laid out his philosophy to editor Gary Groth: "You know, I decided a long time ago that life is short and you might as well be doing something you enjoy. Even if you have to kind of skimp along and starve in the process. ... I've seen so many dear friends not make it as long as I have, you know? Sheridan, Irons, Griffin – each time one of them kicks the bucket, it makes me realize that hey, our time here is not guaranteed. It's a day-by-day proposition. We'd better be doing something that we're getting some fulfillment out of." ![]()

Thanks to Brad Bankston and Austin Books, Leea Mechling and the South Austin Museum of Popular Culture, and John Carrico for supplying artwork for this story.