Our Shostakovich Year

On the centenary of his birth, Austin arts groups join forces to throw the Russian composer a yearlong party

By Robert Faires, Fri., Dec. 30, 2005

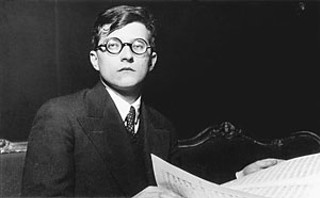

When old Father Time waltzes out the door with 2005, don't be shocked if, instead of a shiny-faced baby wearing a sash that reads "2006," you see a bespectacled, somber-visaged Russian composer bearing that banner. You see, the new year belongs to Dmitri Shostakovich – in our fair city, at least. In a cultural collaboration that's unprecedented locally, 15 Austin arts organizations have joined forces to commemorate Shostakovich's 100th birth anniversary with a yearlong celebration of his work. When the curtain rises on Austin Lyric Opera's production of the composer's 1932 opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk – a work banned by the Soviet regime for several years, possibly leading Shostakovich to abandon opera – we'll be launched into 12 months of Shostakovich symphonies, concertos, chamber pieces, and music for opera, dance, and films, from his first piece for orchestra, written just two years after the overthrow of the czar when the composer was all of 13 years old, to the vocal and chamber works of his twilight years, written in the age of détente. Shostakovich endured Soviet denunciations of his works, Stalin, the Cold War, and even the ebb and flow of modernism. To some extent, he did that by writing music that would please his Communist overseers (a point of controversy with many of Shostakovich's critics), but he also managed to compose works of enormous power, music that pierced the Iron Curtain and captured the ears – and hearts – of music lovers around the globe. Indeed, his music resonates deeply enough that ALO Artistic Director Richard Buckley was inspired to conceive of a citywide celebration and pitch it to a community where he had only lived a few months, and that community took him up on it. The festival – officially known as Shostakovich 100: Austin Celebrates – has been in the planning stages for almost two years. The Chronicle sat down with Maestro Buckley and Austin Symphony Orchestra Music Director Peter Bay and composer Graham Reynolds, both of whom have been heavily involved in the development of the festival, to learn more about why they believe Shostakovich merits this kind of celebration and how it came about.

The Composer

Austin Chronicle: Getting a community to rally behind a single composer's work is a big challenge, but 2006 is also the 250th death anniversary of Mozart. I'd think it'd be a lot easier to do Austin Celebrates Mozart 250 than Shostakovich 100.

Graham Reynolds: It's a lot easier than, say, Schoenberg. [Laughter]

Richard Buckley: That's our next festival.

Peter Bay: But we know practically everything there is to know about Mozart. We know practically everything about his life, except maybe the most intimate things. We know, but we don't know a lot about Shostakovich. A lot of that is based on the history of our two countries. There's so much of the Soviet Union and that system that was and still remains a mystery to most people. There are any number of Shostakovich experts who themselves don't agree on what the truth is. We try to find the answers to some of those questions in the music, but we're not sure. When Leonard Bernstein was playing the Fifth Symphony all over the place and making it a very, very popular piece, he played the end of the piece twice as fast as it's written in front of the composer, and everyone agreed this was a big, triumphal, Beethoven-Fifth end to a symphony. And then we come to read the memoirs, and it's not meant to be a big celebratory ending at all. It's as if you gathered everyone into Red Square with guns surrounding all the people, saying, "You will celebrate." So there's so much of the unknown about this composer. I think it's well worth trying to find some answers by doing as much of his music as possible.

Buckley: He has so many different voices of expression. The first piece I came to, interestingly, was one of his first pieces, Symphony No. 1, which at age 18 or 19 or whatever was an incredible, incredible piece. Symphony No. 5 is a party piece that all music directors of symphonies do. But then pieces like Age of Gold, which is like the ballet music, has this comical, whimsical thing. The first Violin Concerto – that's almost Bergian in terms of the complexity, both rhythmically and harmonically. The First Piano Concerto is almost simplistic. One of the reasons I think he is so criticized is because he has such a wide variety of voices. You drop the needle on Mahler, and you know it's Mahler. I think you drop the needle on Shostakovich, and you know it's Shostakovich, but it's not only that Mahlerian angst.

Reynolds: As far as 20th-century composers go, he's a good starter for a wider audience. Most 20th-century composition is more satisfying intellectually than emotionally, and Shostakovich is satisfying intellectually and emotionally. He also didn't follow the dogma of 20th-century art the way most [artists did]. Most 20th-century visual artists and composers had their stamp, and they stuck with it. You know, you're Rothko and you figure out you're gonna do color squares, and you do color squares, and then you're set. Shostakovich didn't [do that]. And that was partially artistic and partially the ebb and flow between him and the Soviet system, where you do one to please them, then do one for yourself and do one to please them and one for yourself.

Bay: We gravitate toward stories of repression. Why are they repressed? How did they react to it? Can you imagine if Robert Frost was suddenly told by the U.S. government that he couldn't write? Or Walt Whitman, because he was gay, was told, "You can't write those kinds of poems anymore. We don't allow you to do that." Or Philip Glass was not allowed to write this opera [Waiting for the Barbarians, which ALO will produce in 2007] because it has something to do with the Iraq war, and he has to change his style, change his heart. It's not something we can fathom, but that's the kind of stuff that was going on back then.

Buckley: And yet through his whole life Shostakovich maneuvered through that. And my question is, why? I mean, look at all the composers that got out. He could have left. He had ample opportunity. But he had a great desire to stay. He was very successful here, and that was one of the reasons he was able to continue. He wasn't obscure. He became well-known internationally, so the political system couldn't squash him.

AC: Do you feel his artistic direction changed as a result of the denunciations by the Soviet regime?

Bay: He and Prokofiev went in the same direction when they were young. They both wrote very precocious, very popular first symphonies. Their next two symphonies went far afield off the tonal track, they're quite dissonant, and then by the time they each got to their fifth symphonies, they're back home in tonal writing. It seems like Shostakovich was always developing in one way or another without being suppressed, but by the time he started to become controlled he wrote a slew of pieces that were really vapid, to satisfy the higher-ups, but he retained the sort of melancholy, sarcastic edge, and that never changed. I don't know that he had that kind of sarcastic edge beforehand.

Buckley: I think he would have been one of the greatest operatic composers of the century, and I'm really saddened that it got stepped on. Because he didn't really do that much vocal music after [Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk] – a couple of symphonies, some songs, and stuff like that, and the drama that he did was in the symphonic palette. It just totally turned him off, and I'm really saddened by that. His understanding of making a dramatic moment and vocal – When I first did Lady Macbeth, I went, Wow! What we missed, what we missed.

Bay: One of the reasons he went away from vocal music is because when you have a piece of vocal music, you can pretty much figure out what the message is. If you write a symphony, it's all hidden – at least to the general public. Those in the know might understand that this motive might have meant, you know, "Screw you, Stalin," because that's what he told his friends that it meant, but you don't really know what's going on with an abstract symphony.

Reynolds: You don't realize the value of something until it's gone. The value of our open expression with art is much more valuable when you look at someone who didn't have it, and the value of what music and art means to culture becomes much more clear.

The Celebration

AC: The scope of this project is fascinating. Richard, did this originate with you?

Buckley: It's my baby. I can say that, and I should say that, but at the same time, without the partnership of people like Peter and Graham and a lot of the other people in the community it wouldn't have gone anywhere. I started in September of 2003, and our first meeting was February 24, 2004, where we invited absolutely everybody: artistic, educational, radio stations, papers. Peter made the comment that in all the years he'd been here, he'd never seen this type of group of people ...

Bay: In one room. All of us were in one room. It was pretty extraordinary.

Buckley: I went into it with the desire of wanting to do this piece [Lady Macbeth] because I think it's a great piece and it's a piece that should be done. That was how it all generated, and what's been heartening is to see the dedication of the people to follow through. There was a six-month period after we threw out the idea when everyone had to get over the fact that we weren't being daddy with a budget that was going to produce something. "No, we're not going to fundraise it. We're going to make and create this on our own. Everyone's going to do their own thing." And everyone else has continued to get together and drink vodka and eat caviar and talk about what we're going to do. Already we have enough stuff that we've made a statement. We have things like KMFA doing 52 Shostakovich "minutes" – they're actually two minutes – that they're producing that will be on the radio telling the community about Shostakovich. It's being written by a musicologist here, a Shostakovich specialist, and they're going to try and get a sponsor and provide them to other radio stations around the country. Peter's doing how many pieces?

Bay: Two in January and three in the fall.

Buckley: We're doing Lady Macbeth. All the string quartets are going to be performed at the university, by either students or the Miró Quartet. The [UT] band and the orchestra are going to be doing repertoire once they get conductors in. The library is going to show this BBC documentary about Shostakovich's life at all 30-plus library [branches] free to the public. The ballet is doing something. It's snowballed in that way. And what was fun and what's great is that once everyone got involved it was not that big of a deal.

Bay: It's interesting how Shostakovich's centennial has, thanks to Richard's foresight, [provided] a way for all of Austin's arts organizations to get together. We're not necessarily playing with each other, but we're all on the same team. We're all thinking of something that we can do citywide artistically that would be meaningful with a meaningful composer. We have all these incredible resources here, and he's figured out a way to have us all participate. Outside of a handful of pieces this is a very famous composer whose music we know relatively little. There are so many fields of Shostakovich's music that we've not tapped. This is a wonderful opportunity to do so.

Reynolds: If you go see music by these types of organizations, by the end of the year everyone will have heard some Shostakovich, and he won't be a composer that will be up on the calendar and people say, "Oooh, maybe I'll skip that one." He should become one of those composers that people say, "Oooh, I want to see that one." Like, you see Beethoven up there and you don't know anything about that piece, but you know you like Beethoven, so you go. Shostakovich could join those ranks pretty easily.