Long Way Home

Considering the art of the map, as inspired by two local exhibitions and a housewarming party

By Wayne Alan Brenner, Fri., May 20, 2005

I ran into my old friend Sylvia Davis at the Faulk Central Library the other day – I was returning Borges' Ficciones, she was checking out poetry collections by Keats and Eliot – and we decided to spend the rest of the afternoon together over drinks and tapas at Louie's 106. We sat in one of the booths near the bar, eating grilled asparagus and goat-cheese crostinis, exchanging news. Sylvia was, she informed me, about to move into a house in Clarksville with her boyfriend, Dan.

"Next weekend," she said. "So it's not too early to figure out what you're going to get us for a housewarming present."

"Maybe one of those beginner's guides to tact and subtlety?"

Sylvia wasted a smile on me. "We're having a party on the 25th," she continued, "and if you're not there, I'll take it as a personal insult. I'm serious, Brenner: I'll fucking pout for days."

"Please," I said, "not the pouting. I can't stand the pouting. I'll definitely be there."

"Good," she said. "It'll be fun."

"So where is this place, anyway?" I asked. "One of those new things up the hill from the Conoco?"

She shook her head. "No, it's this refurbished old house on Parkinson, a few blocks catty-corner from Nau's Enfield. Except it's catty-corner with a kind of dogleg to it."

"Oh, sure," I said. "It's just a catty-corner dogleg from Nau's. Piece of cake. But is that catty-corner dogleg east or catty-corner dogleg south or what?"

"Here, look," she said, digging a pen out of her purse, grabbing one of the cocktail napkins our waitress had provided, "I'll draw you a map."

The term "map" comes from the Latin word mappa, meaning napkin, although I didn't know this as Sylvia sketched out the streets leading to her and Dan's imminent digs. I didn't know much of anything about maps at the time, aside from how to use them as a last resort when trying to find a specific address in unfamiliar territory; and that map-making companies will sometimes include a nonexistent street in their creations, so as to thwart copyright infringement; and that "X" always marks the spot on pirates' maps – inked by hand on cheap vellum or tattooed on the freshly shorn pates of rum-soaked sailors – where the treasure's been buried.

Now, though, I've been to the Ransom Center exhibition "Images of the World: Maps, Globes, and Atlases," the multimedia extravaganza of "Drawn From Experience: Landmark Maps of Texas" at the Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum, and even back to the Faulk Central Library to research the general history and habits of cartography. And besides the skull-busting amount of information I've gathered, I've also been reminded of what it is about maps that's so immediately attractive: the intersection of information and design.

A map is an abstract and often annotated representation of a place – or in some cases, a thing – that's real or imagined. A place that's real, like Clarksville; or a place that's imagined, like Borges' Uqbar; or a thing like an astrolabe or a mermaid. A map is an abstraction by choice, because an exact representation – through painterly realism or, these days, photography – would provide too much information.

An important consideration for cartographers, then, is deciding what parts should be left out of their creations, because a map works best when it's focused on what will be most useful and doesn't include a lot of extraneous information. But which information is extraneous? And useful for what? Well, that depends on the map. And that depends on the map's intended users.

The oldest surviving map is inscribed on a clay tablet from Mesopotamia circa the sixth century BC; it depicts Babylon at the center of a flat, disclike world. The intended users were other Babylonians, and the intended purpose was to reinforce the idea that, here we are, us Babylonians, right at the hub of all that exists. What difference did it make that other, even later maps showed the Chinese or the Greeks or the Etruscans to also be in the very center of a very small world, according to the nationality of whoever made the map?

It made little difference: They were all wrong in the same basic way. But they were also, all of them, effective in the same way: They conveyed a maximum of information with a minimum of confusion, as rendered via the same methods and materials used by craftspeople in creating other, more purely decorative works. The graphic excellence of maps has thus been heavily influenced by, and often matched the pinnacles of, the general aesthetics of the time.

Sylvia, moving the point of her Uniball Micro carefully across a soft paper square on our booth's table, was creating an impromptu driving map for a friend. She didn't need to reach any heights of craft; she just needed to show me how to get where she wanted me to go.

"Stop staring," she said, pulling the napkin closer to her edge of the table. "You'll see it when I'm finished."

"You sure that's a map, Syl? It looks kinda like you're playing tic-tac-toe."

"I've got your tic-tac-toe right here, pal," she said, not looking up.

Mapmakers in ancient times, though, were often laboring to impress the powers that be; and back then, as now, the better something looked, the better its chances of success. But although a Grecian urn might insist that there's beauty in truth, "better" didn't necessarily mean "more accurate," and objectivity didn't become a common goal of mapmaking until the Greek philosopher Aristotle offered concrete evidence of the world's spherical nature. That perspective, abetted by Alexander the Great's earlier championing of organization via grid pattern, eventually led to polymath Claudius Ptolemy, in the first century, rendering an illustration of our planet based on astronomical data and mathematical calculations.

Ptolemy, who believed that all serious mapmakers should check their assumptions of geographical distance by using an astrolabe, was also the first person to create a projection – the representation of a round globe on a flat map. And, handy fellow, he established north as the direction at the top of a map.

You'd think that would be enough to spark an explosion of purely rational cartography, and it's true that Ptolemy's work influenced the field for the subsequent 14 centuries; but whereas the Eastern world of mapmaking continued to progress, with innovations wrought by the Arab al-Idrisi and others, the Western world (read: Europe) became disoriented in the throes of Christian fever and actually took a great leap backward.

T-O maps of the Middle Ages were simplistic maps designed to express Christian theology, and are so called because the world was depicted as a circle divided (by a T) into three parts – Asia, Africa, and Europe – one part for each son of the biblical Noah, with the Christians' sacred city of Jerusalem in the center. You can see examples of T-O maps in the Ransom Center's current exhibition, where their collection of these and more recent artifacts are arranged, on the nearby walls and in a grid of vitrines on the polished floor, in a manner that would've warmed Alexander's heart.

You can also see maps and globes from the time of the Renaissance and beyond. You might be surprised to know that some of these creations – based on scientific methods and informed by the 15th-century rediscovery of Ptolemy's work – were condoned and even cheered on by the Catholic Church. But the church, unable to stem the tide of rational inquiry, had realized that using the tools of cartography to further exploration would also allow for opportunities to spread its holy gospel. This, along with the search for a westward sea route to India and China, eventually led to the Toscanelli map that inspired Columbus to accidentally discover the New World, to Gerhardus Mercator's much improved projection map, to the first modern atlas (Abraham Ortelius' Theatrum Orbis Terrarum of 1570), and to the magnificent terrestrial and celestial globes produced by Italian master Vincenzo Coronelli in 1688. That atlas and those globes – yes, the originals – are included in the Ransom Center's superlative exhibition.

The better something looks, did I say, the better its chances of success? Certainly, the better its chances of sticking around long enough to be appreciated by people for whom it no longer provides practical use. A thing of beauty is a joy forever, as John Keats, who also gave us that bit about beauty and truth, put it; and ancient maps and globes, especially those from the 1400s and later, are nothing if not beautiful.

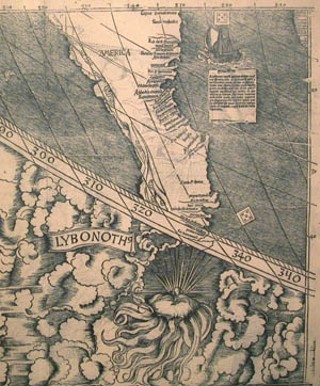

It doesn't matter that Martin Waldseemuller's world map of 1507, the first to use the name America, is obsolete as an aid to navigation and depicts our two nearest continents as little more than a stretched-out shrivel of a land mass. What matters is the effort that Waldseemuller put into his rendering. What matters is the thoughtfulness of his planning, the extreme care with which the lines (of coasts, of rivers, of mountains and seas and ships) were drawn upon the page, and even – in the interests of presenting the information most attractively – the complex ornamentation used to frame his depiction of the planet's surface.

What matters, too, is that this is a recognizable picture of where we live.

The Earth, our enormous, oblate spheroid – its poles slightly flattened, its tectonic plates moving in the very definition of geological time – is the point at which our sense of place in the universe begins to jell. Even if we could disregard the compelling illustrations and the precise methods of annotation, when maps or globes show us our own place in the context of the rest of the world ... when they, however vaguely, provide us with that sense of You Are Here and We Are All Together ... well, who wouldn't be fascinated by such a sight?

The "Landmark Maps of Texas" exhibition at the State History Museum draws even closer to home, with maps – limned on parchment, pressed from woodblocks or copperplates, sprayed from the ink-jets of industrial printers, even rendered holographically in one stunning display – that chart the history of the protean borders and environmental data of this former republic.

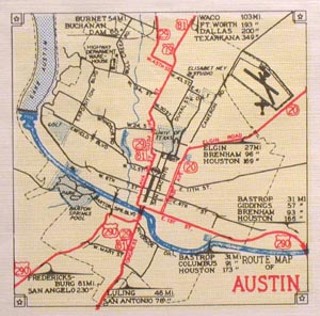

There's the first coastline showing a discernible Galveston Bay, although it's not depicted quite the way it is in your current Rand McNally. There's the erroneous 1847 map by John Disturnell that, attached to the treaty ending the U.S.-Mexican War, wound up costing the United States $10 million in payment to our southern neighbors. There's the version where Fredericksburg and other German settlements are much bigger and more important than Austin. Hell, there's the first map on which Austin is called Austin, and you don't often see such elegant handwriting in these modern times, do you?

With originals or replicas of maps on the walls; with globes and display cases and interactive kiosks staggering the wide walkways; even with computer screens, as the compressed narrative terminates near our highly technological present: This show at the Bullock offers images not only of the planet on which all people spin, but of places where we in particular have been, or where our friends have been, where our children may be, and maybe where our close ancestors once lived their old-fangled, stereoscopic lives.

The human race has been mapping and charting its collective abode throughout history, keeping track of the territories it's gained in exploring, conquering, and colonizing as it spreads almost cancerwise across the planet. Adventurers and imperialists defy old boundaries, breaking laws and shattering limits thought previously unbreachable, and always with documentation moving what was tenuously there toward what is undeniably here and providing bright museum fodder for the generations yet to come.

This is not something that's on hiatus; this is a force that continues to shape our quotidian lives, a progression that's as much a part of our future as of our past. And the seasons change, and the years grind by, and one world-view cedes to the next – in much the same way that the sort of poetry written by Keats gave way to the sort of poetry written by those who followed him – the sort written by T.S. Eliot, for instance, who told us in "Little Gidding" that:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

And so, yeah, here we are again, us Babylonians, right at the hub of all that exists.

Be it ever so humble.

"Here," said Sylvia, handing me the marked napkin in our booth at Louie's 106. She leaned back and poked at her martini's olive with the capped Uniball.

"Nice," I said, eyeing the crude map. "This looks pretty simple – for a catty-corner dogleg kind of thing. 1971 Parkinson, right off 10th."

"That's the place," she said. "And we'll be expecting you."

"Oh, I'll be there, Toots," I told her, smiling. "I wouldn't miss it for the world." ![]()

"Drawn From Experience: Landmark Maps of Texas" runs through June 5 at the Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum, 1800 Congress. For more information, call 936-8746 or visit www.thestoryoftexas.com.

"Images of the World: Maps, Globes, and Atlases" runs through July 17 at the Harry Ransom Center, 300 W. 21st. For more information, call 471-8944 or visit www.hrc.utexas.edu.