Facing the Media

Who is Young-Min Kang? That's what he wants to know.

By Wayne Alan Brenner, Fri., March 25, 2005

His artwork is unforgettable: due to its size, due to its form, due to its transmediation of, most often, the human face. Even when there are no biometrics in sight and the piece is part of a large and impressive group like Creative Research Laboratory's 2003 "Superstring" exhibit, his work stands out like an auk among sparrows.

Jasper Johns is one of his heroes. And Elvis. And Kurt Cobain. And he's been deeply influenced by Ludwig Wittgenstein and Marcel Duchamp.

He's currently represented in the Texas Biennial (Interstate Junction, at Bolm Studios) and at City Hall (Hillerova's Faces, as seen on this issue's cover). He's been recently featured at Studio 107, the Space, the Austin Museum of Digital Art, and San Antonio's the Bower. And if he can't get a new visa by May, he'll have to leave the United States.

Who the hell is this Young-Min Kang?

"I was born in Seoul, South Korea, in 1969," says the artist, who recently completed his MFA in Studio Art at UT-Austin. "I came to Texas to go to school. There's a good art scene in Korea, too, but I was more interested to be by myself in a residential program. I learned something from school, of course, but it really let me spend more time by myself. Because, in Austin, there's no family, there's no friends, I'm kind of isolated here. So I can think about what I want to do and 'Who am I?' and those kind of things."

Kang's exploration of "Who am I?" is what's fueled many of his creations thus far, and the question is complicated by his presence in America and America's presence throughout his younger years.

"I was suffering from identity issues," he says. "When I was in Korea, I was watching all the Hollywood movies, so I had a certain kind of imagination about Americans and American culture. And I'm not sure if I was, if I really liked it or it was more just curiosity. But when I got here, my image of it was broken, and I had to totally rebuild my idea of America." And, it turned out, the idea of himself within America.

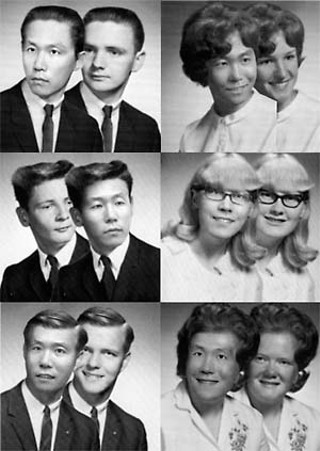

"One of the things I did last year," says Kang, "I found, in a pawnshop, a high school yearbook from 1967. And I was thinking about American culture and what I fantasized about it when I was in Korea, when I was a kid. So I tried to put my face to the faces in the yearbook. To put myself in the context of America, to see what would happen from that. It's kind of a joke – well, it's not just a joke – about my imagination and my experience with this culture."

In the context of this interview, Young-Min Kang and I are sitting at a table in Hyde Park Bar & Grill, eating a late lunch, the capstans of a micro-recorder turning smoothly near our elbows. At least, I'm eating a late lunch, and Kang – who's still coasting on his noontime meal – is merely snacking on fried artichoke hearts.

"There's a certain kind of influence," the artist continues, wiping a crumb from his lips. "America exports its culture internationally. So many people living outside the United States know about the culture, at least a little bit, but I don't know if they realize it correctly. And when I got here, I began to learn how it is – the real things, the real culture."

Of course, much of what passes for real culture in the U.S. these days is generated through, or at least covered by, the news or entertainment media. And Kang, engaged in identity-warping yearbook Photoshoppery or otherwise, is well aware of this.

"I was influenced by the philosopher Wittgenstein, and Marshall McLuhan, and others who were talking about the media," he says. "They concentrated on the situations and ideas of it, and what it's trying to do with its subjects. I'm interested in all of those ideas, so I try to reveal or break apart what is happening.

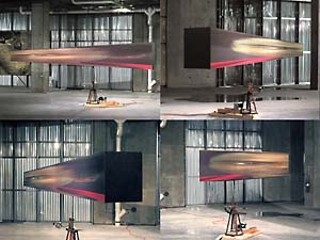

"Like a television monitor," explains Kang, arranging his hands to frame a squarish void. "When you're watching movies or something on television, you must always concentrate on the monitor. Because if you move your vision to the right or left, past the corners, the illusion is going to be broken. Because you're supposed to concentrate on what's happening in the box, not the outside.

"So my idea is to bring a view to the outside of the monitor. I try to break down the media into the physical world. Some of my work, I make sculptures out of two-dimensional digital prints, to make them into three-dimensional shapes. My idea is to break the illusions of media and remake them into something else, to reveal something. I don't know what's going to be revealed, but I try to break it down, as a kind of experiment. Maybe so I can show the truth of the images."

"Ah, artists," I comment, as if sagely, around a bite of blackened tuna, "always trying to show the truth of images."

"My attitude about art and art-making," says Kang, "is that I'm not really different from other people. I'm making art, of course, but I don't think I have a special kind of experience. Some artists seem like they want to do everything to be different: 'Look, I'm crazy, I'm doing really crazy things.'" He laughs. "I just try to catch something in our life. I want to communicate very easy and simple things, but it can carry or imply more important ideas at the same time. My work is more like something that I found, or it's some sort of visual effect that everyone already knows, just tweaked a little bit and popped out for people to see."

Popped out, indeed: most often at several times life size.

"No," Kang demurs, "I've done some work that's small. Almost as small as that." He's pointing to one of the paintings displayed on the restaurant's wall; it's about 3 feet by 4 feet, larger than a lot of what you'll see in galleries around town.

Almost as small as that. So the man's a fiend for the big stuff. Like that piece in City Hall?

"Hillerova's Faces," says Kang, nodding. "I used PVC pipes for that, to wrap the images around, and it's almost 10 feet tall and 5 feet in width. I really like how a piece works with the space it's in. When it gets big, it interacts with the space in a way that small pieces can't; they're more self-contained, and I think that's why I like to do big work."

But often, the bigger the work, the greater the cost. And as any artist who's not, say, Christo, can tell you, cost can be prohibitive. So let's remove that from the picture.

"Young-Min," I say, "what if someone gave you $50,000 to do any project you wanted to? What would it be?"

The artist frowns. "That's a real hard question," he says. "Usually I have an idea about some project, but ... that kind of money? I don't want to do it just for myself, I would do something connected to people in the community. It should be in a public space, and not concerned with my own identity.

What’s it like for Hana Hillerova, an artist in her own right, to have her face so big and so, well, tubally diversified by her friend (and fellow graduate student) Young-Min Kang?

“It’s great,” says the Prague native and director of UT’s Creative Research Laboratory at Flatbed World Headquarters, “because now people come up and say ‘I saw you at City Hall!’ when I haven’t even been there.”

The 10-foot-tall Hillerova's Faces is Kang's contribution to the Elizabeth Wynn-curated collection of local artists' works graphically complicating the walls and spaces of the new City Hall. At that height, it's quite a bit taller than its own subject. "It's interesting to see my face so blown up like that, so detailed," says Hillerova. "Although I'm seeing things about myself that I never noticed were there, and I don't know if that's necessarily a good thing. But there I am."

"Some artists get a lot of money from an organization, and they make an expensive artwork that needs, like, air conditioning, all those kind of things, for preservation? They spend the money on that, and I think it's a waste. Because that money comes from many people, I think, and what do they get for it?"

"But say it's some eccentric billionaire," I plow on. "He's got an extra $50,000 just sitting around, and he figures, 'Okay, I'll give it to Young-Min Kang, let him do whatever the hell he wants with it.'"

"Well, in that case," he smiles, "I would do something big. Something really big. I don't know what, maybe a big print, bigger than I've ever done. I don't know what the content would be right now, but it would be big."

Kang himself is pretty big, as they say, in Austin. And eventually, watch his trajectory, internationally. But he may soon have to be big from somewhere outside the U.S.

"My student visa expires in May," says Kang, finishing off a last bit of artichoke. "I could get an artist's visa, but this is a little hard to get, because it's mostly for established artists, so I'd need a lot of sponsors. The other thing is I could get a job in the United States, like at a school or something like that, so I'm applying for that, too. And the third one is getting married to an American girl. Which is, I don't know, I'm not really getting into American girls, now. So there are some solutions, but this moment is really tricky."

Which means this article's initial question may well become "Where the hell is this Young-Min Kang?"

For now, we're glad he's deep in the art of Texas. ![]()