Renaissance (and Baroque) Man

Curator Jonathan Bober finds the world's great art a home in Austin

By Robert Faires, Fri., April 4, 2003

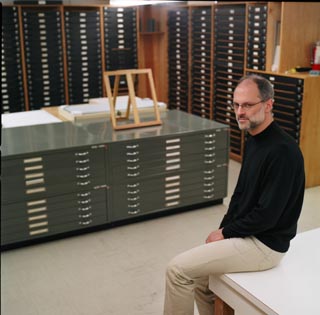

"I'm a pig in deep mud," grins the tall, slender man in the upstairs gallery of the Art Building on the UT-Austin campus. The remark sounds a little incongruous in such a place, especially coming from such a refined figure, and yet given his position -- curator of prints, drawings, and European paintings at UT-Austin's Blanton Museum of Art for the past 16 years -- you can see why Jonathan Bober says it.

This is a man whose passion is art, and here he is in the midst of a glorious bounty of it. In front of him are masterful engravings by Dutch artists of the 16th century; on adjacent walls are equally expert etchings from France and Italy in the same period; behind him hang a dozen etchings from 17th- and 18th-century France and England; and across the gallery hang etchings and engravings by European artists of the last two centuries, and to reach them, one must pass by glorious paintings and drawings from the richest periods of the Renaissance and Baroque eras. The entire floor is luxuriant in portraits of gods, heroes, muses, peasants, saints, prophets, images drawn from Scripture, scenes from Greek and Roman mythology, scenes from village life, landscapes and livestock, rendered by the likes of Peter Paul Rubens, Albrecht Dürer, Giorgio Ghisi, Simon Vouet, Schiavone, Guercino, Picasso. Here is Jonathan Bober, able to ... well, let's say it, wallow in all this visual splendor, the space currently exhibiting 100 prints and 40 paintings spanning four full centuries of European art with heart-stopping breadth and artistic quality, including what Bober calls the "canonical masters" in the Western cultural tradition. And he can not only take pleasure in these artistic treasures; Bober can take pride in the fact that he is responsible for them being in Austin.

Without Jonathan Bober, two of the cornerstones of the Blanton Museum of Arts' holdings -- the Suida-Manning Collection of Renaissance and Baroque art, comprising some 250 paintings, 400 drawings, and 20 sculptures; and the 3,000 prints of the recently acquired Leo Steinberg Collection -- might not be here.

Right Man, Right Place, Right Time

Bober might demur on such a point. When he tells the story of these major acquisitions, he makes a point of including the names of others who played a significant role: the "extraordinarily generous" donors who "get the big vision" when it comes to expanding the collections and UT-Austin President Larry Faulkner, who saw the unique value of the Suida-Manning and Steinberg collections for the museum, for the campus, and for Austin.

Bober's point is well taken. Treasures of the scale of the Steinberg Collection (an estimated value of $3.5 million) and certainly the Suida-Manning Collection (more like $35 million) aren't typically secured by a single individual, especially an employee at a state university, even if the state is Texas. Support must be garnered from a number of key people within the institution, and private support is critical, which in a multimillion-dollar deal these days means multiple donors.

Still, even when he downplays his own contributions, it is clear that Bober was pivotal in these particular accessions. He was the right man; that is, he had the eye to appreciate what was on the table, the presence of mind to call the university's attention to it, and the persuasive skill to argue the case that they could be invaluable additions to the university's holdings, despite the exorbitant cost. And he was in the right place at the right time.

Case in point: It's 1994, and Blanton Director Jessie Otto Hite takes a call from a gentleman in the gallery. He tells her that he's a collector of Italian Renaissance and Baroque art, so she invites him to her office. But as his name isn't familiar to her, she uses the time before he arrives to call Jonathan Bober and see if he knows a Robert Manning. Bober knows. Bober really knows. When he was in graduate school at Harvard, he had actually visited Manning's home in Forest Hills, N.Y., where every wall -- we're talking hallways, living room, dining room, bedrooms, and powder room -- was covered floor to ceiling with spectacular artworks from the Renaissance and Baroque periods. Robert Manning and his wife Bertina, working from a collection started by her father, the scholar and art historian William Suida, had assembled one of the most valuable private collections in the world.

It turned out that Bertina Manning had died two years earlier, and now Robert Manning was beginning to look for another home for their collection. As a native of Mart, Texas, he was hopeful of finding one in his home state. The possibility of acquiring this $35 million treasure seemed, to Bober, "utterly implausible," even for a school with pockets as deep as UT's. But Hite and Bober kept in touch with Manning, paying him a visit in Forest Hills a few months later and seeing the collection firsthand.

Here and in subsequent visits, Manning made clear that he wasn't about to hand this collection over to just anyone. He had a deep connection to these works and to the fact that his life and the life of his spouse and the life of her father had been devoted to the assemblage of these works into a collection. Here was his grand achievement, and any institution that wanted it would have to prove itself worthy, would have to show that it truly appreciated what it was and what it held.

Bober was the point man for the Blanton in this regard. He spent hours with Manning poring over the collection, work by work, discussing in intimate detail each piece's look, feel, subject matter, composition, technique, inspiration, influences, cultural contexts -- in short, any and every scholarly aspect of the work coupled with the sighs and superlatives of a die-hard fan. And when Manning died in 1996, before negotiations with UT were complete, he did the same with the Mannings' daughter, Alessandra Manning Dolnier, and her husband Kurt Dolnier. In her own way, Alessandra had an attachment to the collection as deep as her parents: She had grown up with its paintings and drawings in her home, and they might as well have been the siblings she never had. In Bober, she found someone she could trust with her "family." And the Dolniers offered UT the opportunity to purchase the collection. With Bober and Hite working feverishly to secure support from inside and outside the university, the arrangement went forward. The deal was sealed in 1998, and UT had Suida-Manning.

The Natural

You get a sense of how Bober swayed folks to support the Suida-Manning acquisition as you listen to him talk about a work of art. His unaffected enthusiasm is downright contagious. He'll start with the kind of general appreciation -- "a beautiful piece," "I love this" -- that makes him sound like any Joe off Main Street. But then he'll find details in, say, the contrast in the shadow and highlight of a figure or the gradation of color in the modeling of some fabric or the heaviness of a line under a thigh to give it weight that shows just how much he really sees, but also gets you seeing more than you ever thought you would. And the longer Bober talks -- which can be a considerable time; he says of himself, "I can go on like a fundamentalist preacher" -- the more his enthusiasm turns to ardor and an ardor for not only the painting or drawing or print but for the creator of it and the society that the creator lived in and the artists and cultures that came before and after, right up to our time today. In a few lines on a piece of paper, he can give you the world. (For a sample, see "Seeing What Jonathan Sees.")

Bober comes by his love of art naturally. You could even say it is in his genes. His mother, Phyllis Pray Bober, was an archaeologist, a scholar of Renaissance art and architecture, as well as a scholar in culinary history. His father, Harry Bober, was trained as an artist but became an art historian specializing in medievalist works. Jonathan Bober describes them as "old-time bohemians" who wouldn't join the white flight out of the Bronx, so he grew up in a big house in the heart of New York, surrounded by art and playing great basketball.

Despite his parents' vocations, he was not force-fed culture as a child. Their home was filled with objects from which "there was no aesthetic distance," Bober says. "If I took an interest in something it would be in my hands, I'd be handling it." And what he was told about it wouldn't be "a pedantic explanation; it would be: Feel, think, understand." Harry Bober insisted that his sons "not be dragged to art museums; his attitude was that if my brother and I were going to come to art, it would have to be on our own terms. The deck was stacked against us, and if we were dragged to it, given the environment we were raised in and our parents' own concerns, it was set up for us to flee and reject it." The strategy worked. Jonathan's brother David made a career of interior renovation and custom carpentry, and developed a passion for collecting Japanese art and objects. Jonathan followed his parents into art history, studying at Harvard, interning at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the National Gallery, spending two years as a Kress Foundation Fellow in Milan before starting as assistant curator of prints at the Fogg Art Museum (where he met art historian and print collector Leo Steinberg for the first time).

In trying to articulate what he is drawn to in art, Bober relates it to "the psychology of a collector." That is, he says, "I commune with these things and have spent however many years trying to understand the ways in which they communicate, and I recognize so many and identify with them so deeply, it becomes as any art does: a kind of surrogate or metaphoric self."

Bober aligns this idea with his pathological shyness about public speaking. "I was sick from public assembly any time my class had to sing," going so far as to fake it with "the thermometer on the light bulb, the old classic." But he learned that if he was talking about something, he was OK, and with works of art, he says, "It's not that they speak for me, it's that I speak with them. In public, I'm sharing that dialogue. I'm sharing what I can of how I commune with it."

Evenings With Leo

Perhaps it was Bober's collector psychology that made him seem a kindred spirit to Leo Steinberg when they met the second time. This was in 1995, when Steinberg had come to Austin for a visiting professorship. One Saturday Bober was able to bring the scholar into the Blanton's print room and show him part of the museum's collection: "the conventionally great stuff," Bober says, "but also the offbeat stuff and things I was especially proud of, that I valued especially." As happened with Manning, Steinberg was struck with Bober's knowledge, taste, and passion. But here Bober was even closer to the collector's heart since among his special interests were -- yes! -- French and Italian prints made before 1800.

This was more than a shared taste in style and period. Bober felt, as Steinberg had when he began his collection in the 1960s, that prints were significant, that they played a critical role in the dissemination of cultural ideas and iconography. (See "Prince of Prints.") As Bober will tell you, passionately, about prints: "Until photography, this is it. This is how the Western world knows its imagery. And as I love telling students, probably 80% of the imagery in the West before photography is prints. You need to know the Sistine Ceiling, but know that for every one Sistine Ceiling, there are hundreds of iterations and prints, and this is how the world knew it."

A relationship was founded. Having admired the Blanton collection's mix of masterpieces, canonical work, more eccentric work, and its density in works by the same artist and in the same period (so similar to his own collection), Steinberg told Bober, "You must come see my collection." Though he was flattered just by the invitation, Bober accepted, and from 1995 on, whenever Bober visited New York -- four to six times a year -- he would go see Steinberg in his two-bedroom apartment on the Upper West Side. According to Bober, all of Steinberg's 3,200 prints lived in this small space, in cabinets, in two closets, and under his bed, with only 20 to 30 framed and hanging on the walls.

The typical visit involved Bober dropping by between 6 and 7 in the evening, at which time the two would chat and have a sip of sherry or wine. Then they would order out, usually Japanese. Then they'd start looking at prints. They would start with a school of artist or a period of time or medium, and then, as Bober says, "free associate." "It's the nature of the collection the way he put it together. Incredibly dense with internal cross-references, visual cross-references." This "almost orgiastic looking at prints" would go on until about 1 or 2 in the morning.

From these visits, Bober experienced firsthand this scholar's staggering intellect, his refined eye, his exceptional sensitivity. "There are the collectors who simply accumulate, and then there are the ones who live it deeply," Bober says. "With Leo, the extraordinary thing -- and you never get away from it, whether you're reading his writings or you're looking at his prints or you're talking to him about politics -- is the combination of the mind and the eye and the capacity of language. Leo has such a mind that beyond the ostensible topic and the conventional research he's constantly getting at the deeper structures of things. It's powerful; it's inspiring; it's intimidating to be around Leo for any length of time."

After a year or two, Steinberg felt sufficient trust in and respect for Bober and the Blanton that he began to give the museum prints from his collection and came to gentleman's agreements with the museum over wholesale prices for other prints he was willing to sell. The Blanton obtained some 300 prints from Steinberg, half in purchases, half as gifts.

Eventually, Bober started asking, "Leo have you thought about what you're going to do with the collection?" Steinberg replied that he had the idea of giving others the same pleasure from the prints that he had; they're fish, you throw them back to the sea. Bober began to float the idea of the Blanton acquiring the entire collection, and after some back and forth, a deal was struck and the prints were moved to Austin in 2002.

Now, Steinberg is in the position of coming to visit Bober to see prints. As a rule, Steinberg doesn't travel, but as the first show of prints from the collection was being put together, says Bober, Steinberg became more and more curious. "At every stage, he wanted to know, 'Which are you pulling?' The Blanton extended an invitation to him to come down and see his collection on display, and eventually he accepted. This week, Steinberg pays his long-awaited visit, during which he'll address the topic "What I Like About Prints" in a public lecture on April 10 at the LBJ Library.

Needless to say, Bober is pleased to have Steinberg here. He takes pride in this accomplishment, as he does in the acquisitions of the Suida-Manning and Steinberg collections. "If I were hit by a truck tomorrow, I've done something big and consequential for this institution. It's very substantial and will bless this city that I've loved being in. It will be part of its landscape, a part of its historical landscape and its cultural landscape" for a long time to come.

But there's no truck on the horizon. Bober expects to be around for a long time and aims to show that "the significant collection is not just a one shot, not just a phenomenon; it's part of a pattern of what we can do when circumstances are most favorable. It's the kind of principle that Harry Ransom pursued and that succeeded brilliantly, making [his Humanities Research Center] one of the absolute jewels, a beacon for bibliomanes and scholars of literary material. We move toward becoming that for the visual arts."

He smiles the smile of a pig in deep mud. "There are more collections to come." ![]()

"Prints From the Leo Steinberg Collection, Part I" is on display through July 24 at the Blanton Museum of Art, 23rd and San Jacinto, on the UT campus. "Prints From the Leo Steinberg Collection, Part II" will be on display Aug. 22 to Jan. 4 at the Blanton.

Leo Steinberg will speak on the topic "What I Like About Prints" on April 10, 6pm, in the LBJ Library Auditorium.