Still Lives

Kate breakey brings dead things back to life

By Clay Smith, Fri., Dec. 21, 2001

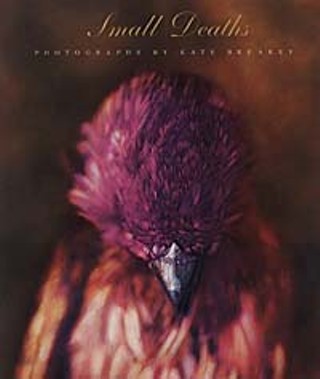

![<i>Cacatua roseicapilla, Galah</i> (1997) from <i>Small Deaths</i>. You're not quite sure [if it's a painting or a photograph], Breakey says, and I actually like that realm.](/imager/b/newfeature/84041/87fff564/arts_feature-12482.jpeg)

In the afterword to Small Deaths (University of Texas Press, $65), a recently published book of Kate Breakey's photographs of dead birds, flowers, rodents, and other animals that she embellishes with paint and pencil, Breakey describes her early predilection for collecting things. She grew up in a rural town in Australia on the Southern Ocean:

I began to pick things up to keep and examine; I collected rocks, shells, feathers, birds' nests, nuts, and pods, and with great reverence labeled, ordered, and displayed them in my little glass case. Visits with my father to the natural history museum in Adelaide filled me with awe and envy and the knowledge that the world was brimming with fantastic, mysterious, beautiful things.

The items Breakey collected as a child are fairly typical; it is tempting to note how peculiar her collecting habits have become -- the red-spotted toad, the chipping sparrow, the blue jays, and the white rose that are memorialized in Breakey's art experience a post-mortem residency in her studio in Tucson, Ariz. But Breakey doesn't exactly collect the objects that end up in her art; that word, with its connotation of permanence, doesn't apply to dead things rapidly becoming dust. The subjects of her art end up in her studio because they seem to be guided there. Some of them are newly dead and others are moldy dead. "My friends and their friends give me small dead things as gifts," she says in photography scholar A.D. Coleman's introduction to Small Deaths. "It is because they know that I will try to give them life." In whatever state they arrive, Breakey doesn't mold or artistically fashion the birds and flowers and insects selected for her examination.

"I set them up very simply," she told me recently at her publisher's office, where 125 copies of Small Deaths were waiting to be signed by her. "I just prop them up and I try not to manipulate them. If they're freshly dead, they're all droopy. I try not to manipulate them. And then I get a lamp, a very simple one, and I light them. And then I move the light around and I photograph them from every aspect and then basically choose an image that I think is the right one." The image is then blown up to human size and Breakey sets it on her easel. She paints it, transforming her photographs into images that are at once bright, magnetic, sensous, and alluring but also strangely formal, imposing, and distancing. In galleries, at their life-like size, Breakey's birds, flowers, and insects seem eerily, almost uncomfortably alive, but in Small Deaths, there is still the weird sense that dead animals can seem remarkably human.

Some of them seem magisterial and inviolate, defiant that their life was so fleeting. Others, clearly defeated, are crumpled and withdrawn, and several of them seem full of rage, with beaks wide open -- screaming, we assume. I asked Breakey about something she mentions in the afterword to Small Deaths, the day she picked up a dead bird and saved it, she says, from a more violent death.

Kate Breakey: The thing is, that day is really just an example of the fact that my whole life, because I grew up in a country town, I always would save things. You'd run out and save things from the cat or save things from having fluttered down out of the tree. So I've been saving animals for a very long time. But I think that the tragic part, and especially when you're young, is you invest in this little thing, this sad little thing, and it dies and you've got this little body and it's a very strangely beautiful thing, the body. And it's still warm and it's dead.

There is a time I think we probably all go through as children -- I don't know whether city kids go through it as often -- but you kind of start to understand what death really is and that this is now a body. Everything that made them "them" -- call it a soul if you like, but I'm not going to get mushy about that -- is gone. It's gone. And it's sort of the same with animals and your pets, whatever. There's this thing that is a very, very beautiful thing that's just a shell, if you like, to use one of those words. But it's a very profound thing when something actually dies; the beautiful thing is still there, as an object which is left. And that's what I do. I photograph them because, in a way, it's like once you bury it, that's gone, too. So I love the idea that I can make something that lasts forever, not quite like a photograph -- an image, something, that is the last thing left after the body is gone. And that it really is the memory of the real thing.

Austin Chronicle: So you try to capture them on film right after they arrive in your house?

KB: Well, no, see, some of them have been dead a long time. Some of them are really on their way to nothing being left of them.

AC: There are so many gradations of decay in your work, I just assumed that you manipulated the objects.

KB: The thing that fascinates me, actually, is that they take on their own life in a strange way, visually. Whatever happened to this poor thing, it's totally on its way to being gone. In a dry climate, things mummify down so that the feathers and the fluff go, but they retain their hardened skin, like a real mummy. And so they stay intact, as apart to moister climates where they just disintegrate and fall apart and the bones go as fast as anything else. But sometimes they're almost indestructible. I just think this is amazing.

AC: Do you think of yourself as a photographer or a painter?

KB: I think I'm basically a photographer. I paint on photographs. I get to embellish them. I'm exaggerating and embellishing. I'm picking up highlights and I'm actually extending this very photographic image into something else and hopefully having it fit somewhere between being a painting and a photograph in that strangely uneasy way. When you look at a photograph, you'll recognize a photograph because you recognize things like depth of field. You know it's a photograph, but it's got so much paint and in the real ones you can see so much pencil. You're not quite sure [if it's a painting or a photograph], and I actually like that realm.

AC: Critic A.D. Coleman writes about the sacred qualities of these photographs in the introduction to the book. Do you feel like you're doing sacred work?

KB: I do. What I like is when I've printed it, when I've finally chosen the image and I've printed it up because I'm committed to it to some extent, and I put it up on the easel, and I'm not in the dark room anymore and I start to color on them, I never know what's quite going to happen. Sometimes it happens and sometimes it doesn't and sometimes I have to work much harder to make it happen, but I get to know them very, very well, and that's part of what I really like, is that you get to know every feather. And so, in fact, you do get to know a lot about the physical aspects of the creature itself and I almost feel like there's a strange relationship. I can meet them eye-to-eye; we can have conversations. I actually do have sort of almost really childish fantasies about me speaking to the bird and what that bird would say, you know what I mean? It's a strange psychological thing. But it's part of working on something for so long and getting to know it so well.

AC: All of the images are about death, but none of them seem morbid. Why is that?

KB: Because we don't really accept death. We really reject it our whole lives. We keep getting older and dying, our bodies decaying, and so we kind of shy away from it and we don't look at it and we don't like images of it. Maybe it's the difference between being a rural kid and seeing it a lot and seeing the smelly carcasses and feeling much more comfortable with it, not feeling that it's horrible and awful, that it's just sort of part of something that happens. I mean, morbid's a funny word. ![]()

Small Deaths will be on display through February at the Wittliff Gallery of Southwestern & Mexican Photography at Southwest Texas State, on the top floor of the Albert B. Alkek Library. For hours, directions, or parking information, call 512/245-2313 or visit the Wittliff Gallery Web site at www.library.swt.edu/swwc/wg/index.html.