When the Dog Bites

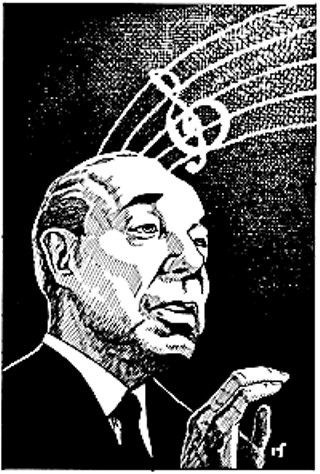

Richard Rodgers composed sweetness and light from deep inside a dark world

By Robert Faires, Fri., Nov. 30, 2001

"My Favorite Things." Just the title jump-starts that chipper melody in your head. Ba-dum-bump, ba-dum-bump, ba-dum-bump, ba-dum-bump ... It's a tune on its tiptoes, aching to spring, and then, sure enough, there it goes -- La-da, la-dee-da, la-dee-da, la-dee-da -- like a ballerina doing leaps, bouncing through all those Hallmark-card images by lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II: "Raindrops on roses and whiskers on kittens, bright copper kettles and warm woolen mittens ..."

Maybe the song makes you cringe (there's a certain age beyond childhood when it's almost certain to). Maybe when that melody gets in your head and won't stop prancing about in there -- La-da-da-dee-da, la-dee-da-dee-dum -- you feel like you're mainlining spun sugar. (One New York critic who saw the 1959 Broadway premiere of The Sound of Music pronounced the show "not only too sweet for words but almost too sweet for music.") It's the sort of unrelentingly perky tune that could lead one to imagine the composer responsible was just a pert Pollyanna who never knew a day when the sun wasn't shining.

In actuality, though, Richard Rodgers was no Mister Rogers. As a new biography makes clear, the composer of "My Favorite Things," and some 900 other songs, knew well what it was to live in shadow; he spent pretty much his entire life there. In Somewhere for Me, biographer Meryle Secrest describes in detail the dark world from which the celebrated composer delivered so much musical sweetness and light: There was his childhood home, a tempestuous place, full of sharp tensions and loud, door-slamming clashes between his fiery-tempered grandparents and his father, a man who could retreat for weeks into "malign silences." There was his marriage to Dorothy Feiner, a union that lasted almost half a century but was perpetually strained, marred by her chronic health problems, his infidelities, and their brittle, bristling personalities. There was his 20-year partnership with lyricist Lorenz Hart, which sparked sweet success on Broadway and in Hollywood but also bitter frustration as Hart's alcoholism made him increasingly unstable and difficult to work with. There was his own body, within which Rodgers wrestled with his own alcoholism, a range of agonizing phobias, recurring bouts of depression, and a succession of life-threatening illnesses. The Richard Rodgers the world saw was a colossus in the worlds of musical theatre and popular song, but Secrest provides a view of the private Rodgers as no giant but a man, a deeply troubled man whose exceptional achievements were balanced by inner demons, trials, and pain.

In Rodgers' world, triumphs sometimes walked hand in hand with turmoil. It was that way with Oklahoma!. Rodgers' first collaboration with Oscar Hammerstein II, which proved to be both a popular sensation (running 2,248 performances) and a landmark in musical theatre, rose from the ashes of his deteriorating relationship with Lorenz Hart. By the late Thirties, the period in which the Rodgers and Hart team produced The Boys from Syracuse, Too Many Girls, and Pal Joey, Hart's drinking had begun to compromise his health. Frequent blackouts and a serious bout with pneumonia were among the earliest manifestations, then came fevers and anemia. There were longer periods of drunkenness and longer hospital stays for drying out. Rodgers found it harder and harder to get work out of his partner and so decided to sever the relationship. When handed the opportunity to adapt Lynn Riggs' play Green Grow the Lilacs into a musical, he approached Hammerstein to be his lyricist. Their first time out together, the new team made history.

While Rodgers was still reaping the glory from that initial collaboration, he suffered a profound loss. In the months after Oklahoma!'s premiere, a new production of the Rodgers and Hart musical A Connecticut Yankee was undertaken. The 1927 adaptation of the Mark Twain novel, which had been a major hit for the team in the Twenties, seemed ripe for revival, especially if several new songs could be added to the score. Hart was approached about the possibility, and in what Rodgers believed was "a genuine effort to rehabilitate himself and to prove that the team of Rodgers and Hart was a going concern," he applied himself to the task and wrote lyrics for six numbers. Unfortunately, once he had completed these, Hart resumed his binge drinking. By mid-November, it was so bad that Rodgers reportedly tried to keep him out of the theatre on opening night. While Hart managed to get in, his drunken behavior ultimately led to him being removed by the manager. The next day, Hart disappeared and when he was finally found by composer Fritz Loewe, he was sitting in a gutter in the pouring rain. He was taken to a hospital, where he was diagnosed with pneumonia. Three days later, he fell into a coma and shortly thereafter died. The true end to the long-glorious partnership of Rodgers and Hart sounded on a painful, ignominious note.

It so happens that the creation of The Sound of Music involved its own emotional turmoil and physical illness. When Rodgers and Hammerstein began working on it in 1958, they had been years without a hit on the order of Oklahoma! and South Pacific. Since their last major success, The King and I in 1951, the team had produced works that could only be considered qualified successes if successes at all: Me and Juliet, Pipe Dream, the television musical Cinderella, Flower Drum Song.

The Fifties had not been kind to the two men, either creatively or physically. In 1955, Rodgers was diagnosed with cancer of the gum and had to undergo an operation in which part of his jaw and many of his teeth were removed. He was drinking more heavily, and by 1957, his abuse of alcohol was so alarming -- one account by Kitty Carlisle Hart has Rodgers consuming 16 Scotch-and-sodas in the course of one evening -- that he was admitted to a psychiatric hospital for four months of treatment. The following year, Hammerstein started having his own health crises; problems with his gall bladder and prostate necessitated two major operations in the summer of 1958. Then, in 1959, in the midst of rehearsals for The Sound of Music, he had another operation for a stomach ulcer. But during the surgery, Hammerstein's doctors discovered cancer and removed three-quarters of his stomach. They told his family he had at most a year to live. The family decided not to share this news with Hammerstein himself, but they did tell Rodgers, who spent the last weeks of rehearsal wondering whether his creative partner of 17 years would be able to help make any final adjustments on the show before it opened.

So these were the circumstances in which "My Favorite Things" was created. That's not to suggest that you should like the song any more than you already do, that the traumas in Richard Rodgers' life somehow justify that song -- or any of his bad behavior, for that matter. The story is offered simply to point out how sharply Rodgers himself felt the dog's bite, the bee's sting, and how he was still able somehow to produce this music of remarkable buoyancy, joyful and radiant with hope. That's instructive in times like these, when our lives are anxious over economic upheaval, sudden deaths from unknown sources, wars and rumors of wars. The world may be plenty dark, but it's still possible to find light. Maybe it's there in the schnitzel and strudel and brown paper packages tied up with string, or maybe it's where Richard Rodgers found it, in the sound of music. ![]()

Austin Musical Theatre's production of The Sound of Music runs through December 16, Tuesday-Sunday, at the Paramount Theatre, 713 Congress Ave. Call 469-SHOW for tickets.