Exhibitionism

(Re)Flex: Opposing Dance Camps

Fri., June 18, 1999

Running time: 1 hr

Sitting in the transformed Covert Buick building, I was impressed by the arts space Ariel Dance Theatre created from a huge showroom with cookie-cutter offices. All the stage components -- dance floor, light trees, risers, and backdrop -- were brought in from the outside and the cubicles along one wall housed work by 10 local visual artists, providing each with a mini-gallery. This centerpiece of this multi-disciplinary compound was (re)flex, a performance piece by choreographer Andrea Ariel with live musical accompaniment by the Golden Arm Trio and haunting film work by Luke Savisky, who filled the entire wide backdrop with simple images such as rippling water, clouds, and scratches in continuous film loops that complemented the dancing without competing with it.

|

|

The event began with a procession of stop/start poses that slowly transformed into a poignant waltz. Moody, circus-like music swirled around the dancers in costumes à la Fellini. Satisfyingly complex groupings appeared and disappeared as one dancer broke out of a group to join another midstep, creating a long-range canon as images of unraveling rope appeared on the screen. The choreography showed the softer side of Ariel, whose movement is usually sharp and angular. I found myself drawn into the world where these characters existed and was disappointed when they disappeared.

If the first half of the program represented the "reflex," the second half represented the "flex." After a long pause (too long), combative and percussive versions of the characters emerged in bike shorts and tank tops, flexing and isolating body parts to pulsing drumbeats. Athletic partnering and unison work showcased the technical virtuosity of the group while a cello moaned eerily. What brought about this radical change was never apparent, nor was the connection between the two halves clarified. In essence, it was a stark juxtaposition of the two modern dance camps: the emotive and the non-representational -- character-driven and three-dimensional on the one hand, unemotional and brilliantly technical on the other.

What began as a departure ended in a more comfortable place for Ariel. I hope that this piece is a sign of what is to come. Journeying into unfamiliar territory is scary and the dividing line between the two camps is razor-thin. What happens in that narrow place could be an entire dance, but it can also provide a distinct connection between the two sides. -- Dawn Davis

Millenium Bug: What Price Technology

Hyde Park Theatre,

through June 26

Running time: 1 hr, 30 min

In the terrific opening sequence of Steven Tomlinson's latest tear on the modern world, the spontaneous, rollicking music of ragtime is systematically reduced to a predictable pattern of numbers. This ability of technology to break down the world's phenomena into simple codes is at the heart of Millennium Bug, the third installment in Tomlinson's "Cost of Living" trilogy, a soulful and daring theatrical triptych which began with the acclaimed monologues Free Trade and Managed Care. Tomlinson, an economics professor at UT, has a tight grasp on the benefits of technology to explain and enrich the human experience, but he also has a keen understanding of its ability to alienate the human spirit. And with both in mind, he asks the very slippery question: Technology can make our lives richer -- but at what cost?

|

|

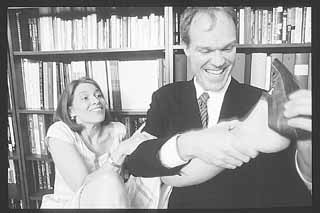

In this Frontera@Hyde Park Theatre premiere, Tomlinson plays Dr. Profit, a financial guru whose VERITAS software fuels a company with plenty to say about the foolish, consumer-driven way we live our lives at the end of the century. Pre-approved credit cards, mail-order catalogs, and online auction sites have become an all-you-can-spend buffet, and some people can't stop munching. Debt is skyrocketing, bankruptcies are up, and for the price of a little indentured servitude, VERITAS can wipe the slate clean, assuring its clients a life that is not only debt-free but profitable. In this capacity, the doctor is summoned by Miss Grants, a vivacious, even somewhat skittish, compulsive spender who has squandered all the money she never had. When Dr. Profit discovers that the otherwise unremarkable Miss Grants has an uncanny gift -- the ability to look at binary codes and immediately pinpoint a glitch -- he carves her a place on the company's development team. But bringing this outside force -- mussed hair, loud laugh, free spirit -- into Profit's hermetically sealed presencethreatens the chain of command and the delicate patterns of behavior VERITAS, and the doctor himself, have worked so diligently to cement.

Tomlinson is examining the interplay between humans and technology -- as well as society's gullible nature -- and in that sense, Millennium Bug contains more glimmers of science fiction than one might expect. He also recognizes the way technology has allowed us to distance ourselves from each other, from the entertainment we choose to the way we communicate or even wage war. The anonymity of e-mail, computers, faxes, and other technology of the 20th century has brought us back to the days when information traveled across unknown, mysterious pathways, and we just hoped it found its way there. The far-reaching possibilities of technology offer us new ways to understand our growing "global village," yet our neighbors seem more like strangers every day.

While at times ominous, Millennium Bug is also damned funny, with the playwright's signature riffs on human foibles: hilarious and caustic yet laced with compassion. Tomlinson is like the star of his own infomercial, with his chatty-cool delivery and the confident tossing, wringing, and pointing of his long, lean hands. Rounding out his presentations is some impressive visual design, courtesy of Austin-based educational software company Thinkwell.com. The creatively rendered visuals add just the right flourishes of humor and enough fancy graphics to remind us just why we're so wowed by all this: the color, the efficiency, the pretty, pretty pictures. As Miss Grants, Annie Suite starts out with a girlish naïveté that effectively chips away as her character gains more and more control. Director Christina J. Moore blends all the key elements -- social comment, satire, comedy, human drama --with a sleight of hand that leaves the 90-minute play rocketing swiftly along, so that by its startling last image, we exit the theatre with rich memories and lingering questions still burning on the brain.

You can never hurt a man if you look him in the eyes, Dr. Profit explains. It is a sentence at the core of what Tomlinson is exploring. Human contact may not be necessary for survival, but Millennium Bug recognizes its power to stir the soul. It is a topic specifically suited to the stage, a place which continues to rail against human isolation, which keeps a stiff arm against the world's homogeneity. And it is a topic specifically suited to Steven Tomlinson, a gifted playwright whose work pulses with passion, inspiration, and the answers to that nagging question of why live theatre is still relevant in a digital world. --Sarah Hepola

Patience: Dandy Lions

Helm Fine Art Center, through June 20

Running time: 2 hrs, 20 min

Ricky Martin can't touch the Aesthetics when it comes to making the maidens swoon, so appealing are these dapper dandies. But the Aesthetics aren't a pop band; they are absurdly affected young men, slouching and sighing across the English countryside, causing young ladies to dress in romantic, pre-Raphaelite drapery and hang on every absurd poetic word. The reigning local Aesthete is the "fleshly" Reginald Bunthorne (modeled on a combination of real-life Aesthete-provocateurs William Whistler and Oscar Wilde). All the ladies dote on Reg, save the one he really desires, and here begin the twists and turns of your standard Gilbert & Sullivan operetta.

This year's G&S Society production, Patience, could be about the latest teen idol or fad, set though it is in the late 19th century. The same rules apply: Taste is out the window, slavery to the hippest cultural icon is way in, baby! All the townswomen are under the spell of Bunthorne, to the detriment of the local regiment, whose hapless dragoons thought to marry the maidens, until the fashion shifted from men in poppy-red uniforms to man in poetic sulk.

Pretty much the only girl with any sense left in her is the titular Patience, a pretty dairy maid without whom, it seems, these young amble-abouts cannot live. Bunthorne, pursued by the maiden mob, chases fruitlessly after our bright-eyed, chirpy heroine. When his rival Archibald Grosvenor (an "idyllic" poet) arrives on the scene to challenge Bunthorne's local notoriety, Patience is caught in the middle. But, as in every G&S escapade, everyone gets what he or she deserves and lives happily ever after.

Any evening replete with the words and musicof Gilbert & Sullivan is an evening of charm and wit, and so it is with Austin's own G&S Society production. Returning director Ralph MacPhail Jr. is no small part of the evening's success. MacPhail, a Gilbert scholar, puts a wealth of dramaturgical and historical insight into his staging: The opening tableau is right out of the original promptbook, for example.

Frank Delvy and James Hampton are stand-outs as poets Bunthorne and Grosvenor. Delvy is all woe with a tricky side; Hampton revels in his character's unasked-for perfection. Both deliver their comic turns subtly or outrageously. Rose Taylor plays Lady Jane, the dowager-maiden clinging to her hopes for Bunthorne's affection. Taylor performs the evening's best song, "Sad is that woman's lot," filling it with self-deprecating humor. While the women's chorus sings and moves with confidence, the same cannot be said of the men: The dragoons plod just a little too much. Leonard Johnson is the exception, with a big voice and big personality as the unwilling Duke of Dunstable. Oddly, when the dragoons don the namby-pamby gear of the Aesthete, they appear much more comfortable -- and they win the ladies' hearts. As Patience, Cynthia Hill posesses a lovely voice and fresh-scrubbed innocence, though it is perhaps a little too fresh-scrubbed. Her naïveté is pretty hard to swallow surrounded as she is by the swooning maidens, drooping poets, and stomping soldiers; imagine not noticing today's famous faces (history's dungheap of tomorrow) peering out from covers of magazines at the local checkout counter.

This operetta may prove that the ephemera of today's icon is just grist for the sardonic mill. So Ricky Martin is an Aesthete of sorts -- he certainly exhibits the requisite preening and popular appeal -- proving that Messrs Gilbert & Sullivan have created in their modest Patience a sly commentary for the ages. -- Robi Polgar