https://www.austinchronicle.com/arts/1999-05-14/521993/

The Thing Unspoken

By Robert Faires, May 14, 1999, Arts

Why? What is it within us that keeps us from expressing a sentiment felt so powerfully?

|

|

But Cameron's exploration didn't end there. It went on to lead the native Australian on other journeys, into more unfamiliar territories. In developing a revised version of Knowledge and Melancholy, Cameron has ventured into new realms of creativity, expanding the role of movement in her work and entering into a full collaboration with another artist. And she has done all this while making another journey, this last on the simplest of planes, the external: to a city half a world away from Cameron's home turf.

This week sees a sort of culmination to these latter journeys with the premiere of Knowledge and Melancholy: A Live Libretto at the Zachary Scott Theatre Center. The new piece reflects Cameron's further exploration of issues of loss in collaboration with one of this city's pre-eminent artists, the creative pioneer Deborah Hay. The two met when Hay was in Australia for a residency and Cameron took part in one of her large group workshops there. Cameron was so taken with Hay's philosophy of movement that she pursued a mentorship with Hay and developed a project called Choreographic Theatre, in which Hay, Cameron, and Australian director Barry Laing led a two-week intensive workshop for actors and directors investigating the relationship between choreography and dramaturgy. That has led to the two working as creative partners on Knowledge and Melancholy.

The expanded version features both Cameron and Hay. Both speak. Both move. And while that may not sound so radical on the face of it, for artists as focused on their respective disciplines as these two are, as singular in their approaches to their art, such a collaboration amounts to putting on a new skin, learning anew how to walk, shaping the words for a feeling you feel in the deepest chambers of your heart and giving them voice for the first time. They shared their impressions about the collaboration, about the piece, and about speaking out during a lunch following their rehearsal on April 30.

Austin Chronicle: I'm curious as to where each of you are in terms of collaborating with other people.

Deborah Hay: I do group work. When I was in Australia, I made a group piece. A lot of my workshop residencies involve performance with groups.

AC: Have you done much one-on-one collaboration?

DH: I have done quite a bit of one-on-one collaboration, but not recently. It's been a large part of a lot of my earlier work.

Cameron: I feel as if I work solo, but I have had several major collaborations within that work, one with a composer at one stage, for about two to three years; it was really a long period. But my work's been solo performance primarily. And this is the first time I've worked with another performer, working equally with that text. It's quite wonderful for me. It's the first time anyone else has ever said my text, the first time I've ever heard it come out of somebody else's mouth, so that's thrilling.

AC: What does it sound like?

MC: Great.

AC: Are there qualities that you're hearing that you didn't expect to hear?

MC: There's a lot happening. Because Deborah's working with the choreography and the text, I am seeing something completely other; because the two things are running parallel and not in a descriptive relationship, meaning is swirling more. I think that's really interesting. And then certain things land with an emphasis that just revealed it as new to me.

AC: You had not done text work at all before this?

DH: I tell a story of a dream in Voilá, but that didn't even feel like text to me. It was, I guess, but there's something kind of grown-up [about this], the feeling of being a kid and now I'm grown-up because I have a part. You know, "Now I'm real serious, I'm an actress speaking lines" -- it has all of that stuff in it.

But actually my worst rehearsals are the ones where I hear myself sounding like an actress and it's awful. Suddenly, I stop, I say, "What do you think you're doing? You have absolutely no experience sounding like an actress." So I've had to go back. It's been a real confrontation. For me to be able to do it with no experience acting, really, is for me to go and just find a way to say it so that I can hear something real in there for me, in the moment that's right for me to say.

|

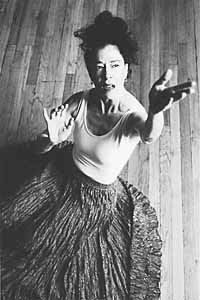

Margaret Cameron |

Digression One: The part of rehearsal I see features the first two segments of the piece. Cameron performs first, then Hay. The women's styles are patently different -- Cameron's intense, her voice resonant, completely invested in the words she speaks; Hay's easy, almost offhanded, yet possessed of a powerful focus, every gesture, every movement arising from some totality of purpose -- still, the styles complement each other, much like one person beginning a thought and another person finishing it. As we lunch, the two collaborators actually do this -- finish each other's sentences -- and one can glimpse something more of the nature of this collaboration: a mutual respect for the other's investment in and command of her art, and perhaps a desire to find in the other a new way to complete herself.

The two refer to the similarities of the different sequences in the show, how most of the movement is drawn from the same template.

MC: I really like your way of describing it as a DNA structure. It's a DNA structure, but it has different ...

DH: Different manifestations.

MC: And mutations. Generations. Mutations. If you are working a DNA structure but you don't control the beast, that's interesting. Because it's like the string on the kite. It's like you're anchored, but the kite is going around. And you as a performer can just go, "Wow. Look at that." You can watch it. For me, that's what's really interesting: To pin it down and watch it so you're not controlling it, nor are you controlling the language.

DH: That's my favorite line in the whole play: "When I decided to give up authority as a modus operandus while performing, I could barely stay awake."

AC: You spoke about how language can dominate; part of what I like so much about seeing text and movement together is that I feel engaged consciously and subconsciously simultaneously. I'm absorbing from more than just the words.

MC: But it's hard to get the both going, like two different channels -- really two different channels, with neither being compromised. Then they create relationships which can be observed. That means the performer doesn't have to create the relationship. You're just trying to operate two pure channels and let them both have their heads ... well, heads and bodies. Then you can witness the relationship.

AC: How do you provide feedback to each other as the work is developing?

MC: We watch each other and comment if there's something to say. I think there's a lot of conversation going on in watching each other.

DH: I think so. It feels more like a directorial role than a choreographic one, but maybe I shouldn't make that separation. Maybe they're together. But it's been wonderful. It seems that each time we go through the practice of it, something in the next practice is changed because of it. I mean, it feels like a very thorough collaboration. It feels thorough.

MC: I think because I'm all text, it's as if we're two ends of one thing and that those are the two things linking it together. So it feels very equal in that sense.

Digression Two: The two talk at length about the costume designer, Esther Marquis of the Alley Theatre. Earlier in the week, she had fitted both of them for their costumes, and the process had taken hours, basically because Marquis had just taken bolts of cloth and pinned them onto the performers' bodies. Though it was a long and tiring process, both women were enthusiastic, almost rhapsodic. For them, what mattered was not the time involved, but the care, this craft: Marquis was fitting them in the most personal and complete way that a costumer can fit a performer. In their comments about Marquis, there surfaces again that shared sense of respect toward an accomplished artist, only here it suggests something of the similarity of these two artists, the ways in which they mirror each other. Curiously enough, they will be physically mirroring each other in performance. Their costumes will be identical in cloth and cut, and Hay will don a wig in the color and style of Cameron's hair. I have a sense of the lines blurring between them, and it seems to echo comments they make about the piece, divisions between intellect and heart, performer and spectator, self and the other, that mingle and blur when the relationships are defined in certain ways.

We veer into a discussion of the themes of Knowledge and Melancholy.

AC: The discussion of loss. Is that something you've been concerned with as a theme before?

MC: No, it was really this text. I became interested in all the kinds of things that can happen in losing authority. Words carry so much meaning for me. So loss ... to me one of the words that relates to that is poverty, so when I see the word poverty next to loss, I go, "Poverty. Simplicity. Beauty." They line up. It's in that way, via the relationship of words, that I started to wonder if there was a fear or limitation in accepting an experience of loss that had a relationship to one's capacity to experience beauty, to perceive beauty.

DH: There's a line in there: "Understanding loss is the recognition that we have loved. What a strange lesson."

MC: It's ... how can I describe it? I wondered if simplicity of feeling was difficult to receive or accept. I had written these lines: I miss love. And I wondered, how can I say that? How can I say it? It's one thing to write it. How can I say it to someone? And I feel, "No, I can't. You can't say that." And so I go, "Why can't I say that? Why can't I say it? It's simple, and it's true. I know it's true. So if it's true, why can't I say it? I miss love." So I get very interested in my feeling that I can't say it. So I say, "Is it too simple? Has it too much poverty about it?" It is an expression of loss. "Are you embarrassed to hear it? Why??" I ask.

DH: There's something else. In the workshop, I was asking about ... I can't remember what my question was, but Margaret's response was she was interested in the four humors.

MC: Yeah. Melancholic, sanguine, choleric, and phlegmatic.

DH: Those almost sound Shakespearean, don't they?

MC: They are forms of one's nature, they're kinds of intelligences, they're avenues of feeling. They have a kind of intelligence.

AC: So is that where the title ...?

MC: Knowledge and Melancholy. I was trying to ... well, there's a line that best describes that: "My intellect, locked in my heart, arrives at the limits of what I am allowed." So it still relates to perception and it relates to feeling, and if certain feelings are not given value or credibility, they're a limitation to the intellectual. I was arguing for intellectual hearts, via the humors maybe, because there was a whole medical-scientific world that didn't split us up like that.

AC: Did these themes strike any chords in you?

DH: When I heard Margaret say that, I thought, "When I'm dancing, all of these things are going through me." Margaret's language, what she has brought to me in terms of my own work, is an articulation of these moments, which I don't stop to examine very much. I know that they're there. I feel like audiences [see them;] from the feedback that I get, people see all kinds of stuff. I know that they're running through me. They're dancing me, I'm dancing them. But I haven't stopped to examine them. And I think that's one of the most exciting things for me in working with Margaret: being able to stop long enough and look at them, make me aware of them.

AC: Have you ever felt a reluctance to express a simple truth in the way Margaret was describing?

DH: Not in terms of movements. One of my favorite dances when I had images for dances -- which I don't anymore -- I can remember doing Little Brown Stick dance. Or in The Other Side of O, it's the movement of grief. If I do the movement of grief, I recognize the fact in performance. I'm not interested in creating grief inside of myself and stopping long enough to examine what I need to create. I know grief is there. So I can be in the movement of grief and let go of it. I think that's sort of the difference. I'm working in the microscopic, the hairline fracture of grief, where Margaret is working in this other realm where it's printing itself out in all of its colors and forms and shapes and textures and bodies.

MC: And what fascinates me about that line "I miss love" is that while I can't say it, it remains about me. When I say it, I don't hear me at all. I hear a whole lot of people. When you said microcosm, it's like I discover, then it becomes totally other, totally objective. Then it can be said, you see, because then it's got nothing to do with me. It has absolutely nothing to do with me. I'm a mouthpiece. It's a mouthpiece. They're words that we'll fill with shape if they're relevant. So if you put the shape of "I miss love" in space, if they're relevant, the emotional body is gonna rush in and fill it up. I really like that idea of language as shape without attachment, and if they're relevant they fill up, not of their own doing.

DH: And that's the same thing with the movement of grief. If it isn't about my grief, but it is the shaping, then it fills up with the audience's experience.

MC: And that's very theatrical. It's actually theatrical because it means you're then a form which fills. It actually has the possibility of epic, in a way, you know? An epic dimension to it. I don't know, classical or something.

AC: It puts me in mind of ancient theatre with masks, where you weren't seeing the actor's face experiencing grief. You saw a mask that expressed a sort of universal grief, which is what your movement of grief describes. It's also kind of related to that classicism you're talking about. It's a touchstone for all of us who know that emotion and the experience of it.

DH: It also shifts the the experience of performance and -- and I'm thinking this out loud, so I don't even know if it's true, but -- it takes it out of declaration and into a place of inquiry.

MC: Yeah.

DH: I think about just that opening of "Close your eyes," and playing that out and performing that, not declaring it but setting yourself up with it like a proposition as the performer. What if? Actually, that's my favorite new teaching tool: I put "what if" in front of everything I say. The interesting thing is, when you say "what if" at the level of performance at which I think we're talking about, where you're not passive, where you're not behind the beat of listening, it's sort of your "what if" has to be at that ... you have to be right on top of hearing and responding, not being behind yourself.

Knowledge and Melancholy: A Live Libretto runs through May 23, Thu-Sat, 8pm, Sun, 2:30pm, at the Zachary Scott Theatre Center Whisenhunt Arena Stage, 1510 Toomey. Call 476-0541.

Copyright © 2024 Austin Chronicle Corporation. All rights reserved.

Deborah Hay

Deborah Hay