Every Last Word

Vincent Gallo: The Complete Transcript

By Mark Fagan, Fri., Nov. 30, 2007

Vincent Gallo is a man of many words. Many, many words. The Austin Chronicle spoke with Mr. Gallo via telephone from Los Angeles on Wednesday, Nov. 21, between 4 and 5pm, Central Standard Time. For a fascinating peek inside the mind of this eccentric artist, see the full transcript below.

Austin Chronicle: Hello, this is Mark.

Vincent Gallo: Hi Mark, this is Vincent Gallo calling.

AC: Hey great, thanks a lot for calling.

VG: Oh, no problem, no problem.

AC: So, I'd like to talk about the new band. Is it pronounced "rice"?

VG: I pronounce it, to be quite honest with you, "R-R-I-I-C-C-E-E," but others have called it "rice," and it's nothing that is offensive to me. It makes sense: It's the word "rice" spelled twice out. It makes sense that people would refer to it like that. Just like PETA, people would call it "peta." But if you call it rice, in a sense that's what you're doing, because it's R-R-I-I-C-C-E-E, which stands for a whole bunch of other things.

AC: Yeah, where did it come from?

VG: It came from – hold real quick, one quick second.

AC: OK, sure.

[Eight-minute pause while Gallo puts The Austin Chronicle on hold.]

VG: I am so sorry about that, man. An emergency's just come up with our flight cases.

AC: OK.

VG: I mean our road cases.

AC: All your gear?

VG: Yeah, all our gear. And like, they're messing it up. If I can take five minutes and just call you back, I'll give them everything I can give them now, and then everybody will just have to wait until I'm done with this interview.

AC: OK.

VG: Am I taking time off of your day or anything?

AC: No that's fine, and I only need about 10 minutes of your time. So you're going to call me back in like five minutes?

VG: Yeah, it'll be no more than five minutes.

AC: OK, great.

VG: I'm so sorry. I apologize.

AC: It's no problem at all.

[Gallo calls back]

VG: Hey.

AC: Hey, how's it going? Did you get it all straightened out?

VG: Yeah, sort of. Not really, but I feel I would rather talk to you right now.

AC: Well, great, thanks for calling back.

VG: The case business is really a rough world out there. What's so great about the case business is it's one of my best talents, my only talent, my only god-given talent, because everything else I had to overcome my handicaps, my mental and emotional handicaps. But my only talent that God gave me – I'm gonna give you this and instantly you're going to be better than anyone else – is boxing, crating, shipping, and organizing, so because I have to delegate that sometimes – I have to have people build things – it sort of translates in everything that I do the way that I have a system and that way of doing it perfect. When I watch other people box something, ship it, tape it, crate it, move it, build something for it, I just go nuts, I can't handle it, so I now go to places that are, like, a hundred times more expensive than other places, just because I want to be able to be indulged in my fanatic perfectionism. So if I want ... 30 percent more gloss than the sample or something, it's got to be like that.

AC: Well, it sounds like you'll always be able to find work.

VG: [laughs]

AC: If you ever want to leave the entertainment world.

VG: Oh, I've left the entertainment world years and years ago.

AC: I hear you.

VG: I'm not exactly sure what I do now [laughs]. Do you ever notice how people on the Internet now, on blogs and stuff, how mean-spirited everybody is?

AC: There's no interaction with whoever, whatever they're talking about, and they're not being a participant.

VG: No, in any way. They're not sharing information; they're not sharing a real exchange. They're really judgmental – really aggressive, really dismissive, really dark. They remind me of all the political protesters, their heart just gets so full of darkness. But for some reason – because I collect things, too – if I go on websites for certain kinds of guitars or certain keyboards, once people know that I'm somewhat known or a public person even on the minute level that I am. Years ago, if you found out that your favorite football player, or any sort of celebrity, on any level, actually showed up at the sporting-goods store or at the guitar shop or something, people would be very excited, even if they didn't like the music. They would be respectful, the salesmen, everybody. When I'm on a blog – I'll go on a blog for, let's say, a certain kind of bass guitar, a certain kind of keyboard, a melotron or something like that – some instrument. As soon as people know that I'm on there, they start complaining about rich people buying up all the instruments as if they're victims. ... They start immediately insulting everything I say or do, to the level that you've never read hate like that ever in your life. Which brings me to ... have you ever been on my website at all?

AC: I actually have, yeah.

VG: OK, so I believe that we're all earthlings; we're earthlings.

AC: We're all people.

VG: Yep. All people are simply earthlings. To think of us any more segregated than that is buffoonery. OK, let's say human beings – you want to go that far? We're human beings, OK. To break it up into gay, black, African-American, Native American, vegan, vegetarian, raw-foodists, you know Buddhist, raw-foodist, vegan, homosexual, African-American, whatever it is that you decide to create for your identity in this mental world, which has nothing to do with your soul anyway. It's so embarrassing to me that I've created, let's say, a vocabulary or a character that sort of mocks and mimics that stuff, because the only thing I find entertaining about it is in humor. ... So I play this role. I use these slurs or these outlandish concepts, which are so obviously meant to be funny or absurdist, at least absurdist. No hate group has ever reached out to me. No gay-bashers, no homophobes, no nationalist, no right-wing Republican, no, you know, Christian, whatever you guys think I am. Whatever it is. None of them, people defined as the black shadow, have ever reached out to me in camaraderie. No one's ever written me an e-mail and said, "I'm a racist, too; I really like your website," or "I hate gays, too; you're a genius." What I do get, though is the most hateful spewing, horrifying, horrifying violent threatening ugliness from the socialistic idealists or the people who are caught up in protests, in righteousness. The most ugliness that you've ever read in your life. In your life. You know like: "I'm a fag, man. I've read what you wrote ... and I'm really offended. I'LL FUCKING KILL YOU, MAN!" Like that.

AC: Does that have any influence on what you do say now?

VG: No, because, believe it or not, I am not a reactionary or a provocateur. I think completely on my own. Whatever it is that comes from me comes from whatever thing is making me laugh at that moment, whatever I think is funny, whatever I think is missing. Actually, whatever I think is missing is more influential than anything else, so when people ask me who my musical or film influences are, it's such an absurd question to me, because the people that I like, for example, and listen to a lot are so far off from what I'm doing. ... I like Michael Jackson; I like Anita O'Day. The people that I'm listening to every day have nothing to do with the work that I do, on any level. Maybe I relate to some sentiment or some discourse or fragileness or melody or something that I like that made me like them that would attract me to some of the things that I've made or make me want to make them, but not in that way. Not in an influential way. No, I don't react to what people say. I am surprised, though. I am surprised. I'm surprised the same way when I go on a blog for a certain keyboard or guitar that people have the chance to talk to somebody with a lot of experience or a lot of instruments or connections to other famous musicians that they like where they can utilize me. I'm there open, it's Vincent Gallo; yes ... I'm godfather to Chris Squire's son. Chris and I both play Rickenbacker basses. So instead of them saying, "What is Chris' bass like?" they say, "What are those collector actor Hollywood ...?" They go into rants, like total rants.

AC: If they even know who Chris Squire is.

VG: What did you say?

AC: If they even know who Chris Squire is.

VG: Yeah, exactly.

AC: What does inspire what you do musically? Is it just a collaboration with who you're working with or the ...

VG: You know, what inspires me musically – I got a guitar when I was very, very young, and I was into my, let's say, 25 LPs. I had more LPs than any, let's say, 9-year-old my age. Twenty-five like brand-new, mint LPs that I had bought for a buck to 2.50 each, whatever they were at the time, and they were really important objects to me. I was not really allowed to have a hi-fi setup or a phonograph or records really, and so I was limited to when I could listen and where I had to listen. I had to have it set up in the basement, in a corner, put it all away each time. Even though my father was a singer, remarkably musical, it was sort of stifled. And so I got this guitar. I bought this guitar from a music shop a couple blocks away from our house that was used, a used Vox guitar. It turned out to be a British-made Vox, which is, in today's market, very special, because most of them were made in Italy. But this was a British-made Vox guitar, sort of Stratocaster-ish-looking Vox, in light blue, powder blue. And I didn't know anything about action, or string gauge, anything like that, but it was a very challenging guitar to play. It had very high action, very thick strings, was really miserable. And I learned this song, which is sort of a scene from Romeo and Juliet called "A Time for Us," 'cause I started taking lessons with this teacher, and I could sit in front of a mirror all day long and look at where to hold the guitar. I could sit there and just strum along with a record, not playing anything for hours and hours and hours, but I couldn't discipline myself to learn how to read and to practice playing other people's music. I just couldn't do it. And my need and my yearning and my desire to create music was so overwhelming at the time. I mean I was a hi-fi collector, a record collector, a guitar collector in a sense –even though I only had one at the time. Music was everything to me, and my idols were only people in bands, and I snuck into concerts; it was everything that I liked. I just couldn't connect with it like that. So in a sense I was immediately turned off to music because of what I felt were the demands or the requirements. ... I had friends in the neighborhood who were in the high school band, or they were in their bands, and they were doing cool music and stuff, but I couldn't get into that. I started to express my creativity in different ways: through aquarium hobbyist and building remote-control planes, playing hockey and baseball and football but designing my helmets. I had the first white cleats in Buffalo, very into aesthetics and concepts and expression that was not just sports or not just motorcycles or not just having a pet. They had to do with building aesthetics and sensibility, but I just could not do it in music, until a group of friends of mine – let's say 12-, 13-year-old friends of mine – some freaks in Buffalo went to go see –actually we were 11, because we were still in fifth grade – we went to go see a band in Buffalo that was doing Yes and Genesis covers. And the band was headed by this guy named Mark Freeland, who just passed away recently. We saw them perform some Yes and Genesis covers, which I had never heard really at the time – this is what actually turned me on to that music – and they could play the instruments really well. And so I got really excited and re-excited to try a little harder, and this time I switched to bass, because I liked very much the bass player in the band, and then when I listened to the Yes records, Chris Squire immediately became my hero, but again the same thing happened. ... I got a little better; I could play a couple pieces from a couple pieces of music, but again, because Buffalo invests a lot of energy into very conventional thinking, like I'm thinking I have to play somebody else's music to qualify as a musician. This is what musician means, and it means doing this, and this is the protocol for a band. Well fortunately the leader of that progressive rock cover band, who was so brilliant and so interesting as a person, by the time I was, let's say, 13 years old, he was moving on to more experimental music, and through him I was turned on to bands like Suicide, some of the earliest No Wave or noise bands and some electronic things and just the idea ... and punk, really. We brought the Ramones to Buffalo like the first year that they had a band, which is where I first met Johnny Ramone, who later became my best friend of my whole life. Just this idea that I could play music without following the protocol influenced me in more ways in my life than anything else. In what I decided to do, how to make a living, how to justify what I felt I deserved when I made a living, how to think in all other forms, you know even as a machinist, as a metalworker, whatever it is that I was doing. I had respect for the people who could follow the protocol; I had respect for people who could follow traditions, and I respect especially craftsmanship, but I began to develop my own techniques, my own craftsmanship, and my own approach to everything that I did, which was natural anyway. It wasn't like a conscious moment. That person, that Mark Freeland character, he didn't teach me to think like that, because I always thought like that; I always figured everything out – even in school – that way, but he gave me confidence, or let's say he was the first person who reflected back to me that it was that I was doing ... he was a fan of mine immediately. So, in other words, his excitement to watch me turn in something – my band played at one of his street festival things, and we did basically a really primitive performance, and he was like, "You guys are fucking brilliant!"

AC: He was supportive.

VG: Yeah, I mean, it was so supportive that I can't even tell you how important it was. So at 15, 16 years old, I wind up in New York City, and I hook up with Jean-Michel Basquiat, and we're in this industrial sort of noise band, but very industrial band. Very methodical, simple, minimalistic industrial music, and at the time, I'm really thinking it's the most beautiful music in the world. It's so beautiful, I'm feeling like I'm in the best band in the world, and I'm not a provocateur, of course, and I'm not there in that band being contrary, and we're not intentionally doing music because we're reacting against the mainstream. We're really moving towards love and light and what we think is beautiful. And so, my father, who's a very traditional singer –he's a crooner with perfect pitch and stuff; he doesn't love music, though – I went to Buffalo once when I was 16 years old on my first visit back ... after the mood there inspired me to leave home and town. And I had a cassette with me of my new band Gray's recording, which probably went something like: "[explosive noise, white-noise sound] toot, toot, toot [explosive noise, white-noise sound]." Like something like that. But in the most beautiful form of that. And so my father ... I saw my father. I hadn't seen him in six months. I'm now living on my own. I'm 30 pounds skinnier. I've already been photographed by gay photographers, like Robert Mapplethorpe and David Armstrong, and I've worked in some dark circles doing dark things, and I've lived on the street, I've banged a pretty bizarre selection of women – a 60-year-old, you know, a stripper, whatever. I've been in the hardcore circles, and I'm there with my father, and I'm like, "Listen, I'm in a band, and I want to play you our music." And I remember my father saying: "What do you mean your music? You can't play music. You're a fucking retard. You've got no ear; you can't do anything with music." And I go, "Well, I'm in this band, and I think you should listen to this." And so I put the cassette on, and it plays that music that I explained to you, and immediately my father like smashes the cassette deck; he literally pounds his fists down on the cassette deck, and he grabs me by the throat, and he tells me like this: "What are you, a sick, a sick person? Are you really a mentally disturbed person? You play me this sick noise, sick sound, you call that music? Are you really sick?" And he basically threatened, basically – because I was still a minor – he basically threatened that he would have me institutionalized, that I was a psycho. Now, at that moment, I'm telling you – I am telling you the honest truth – that I thought he would like the music. I thought that I had finally found a connection between him and I, that though what I was doing, I knew, was a little unique, you know, different, I thought that because he was a musician, he would be able to get past himself and be open and see the beauty that I had seen there.

AC: And you're his son.

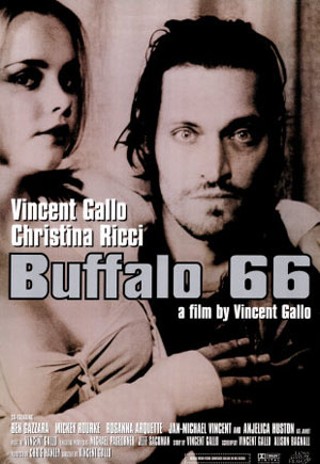

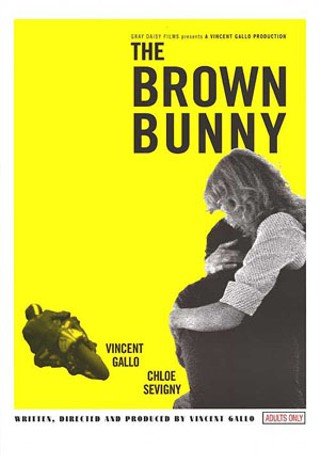

VG: Yeah, and I'm his son; I thought that maybe he would maybe also give me the benefit of the doubt, though that was sort of sick of me to think such a thing based on my experience with him in the past. That was my reaction from him and from a lot people around him, a lot of other people. Now, that goes back to 30 years ago, 28 years ago, to be exact, and you know, it's happened sometimes where I've gotten a similar reaction and other times when I've done what I think is my most challenging work or difficult work, people have been able to relate to it in a really simple way. I mean, Buffalo '66, when I was thinking Buffalo '66, every idea that I had for that movie I had to fight for, fight against to get on the screen, thinking the whole time no one was ever gonna see this movie. Even the film stock was impossible to develop. So when people embrace the film, or when they come up to me and they say, "Oh it's my favorite; it's so funny," it's interesting that it has appeal on many levels. It has basic appeal ... people could connect with it in all forms. And so that's a surprise; it's nice. But that project was no less inspiring or original to me or coming from me than anything else that I've done. It's really important for me now at this point, because ... the resentment against me is always based on this idea that I'm a provocateur or that I'm pretentious ... Do you really think I spent 3 1/2 years making a movie, losing my house, losing my girlfriend, going to the hospital twice with a nervous breakdown, losing my life savings, losing my hair, you know, so that I could be blown by Chloë Sevigny? I mean, do people really believe that?

AC: Not that much thought is put into it, though.

VG: I mean, do they really believe that, though? That people's work is coming from such suspicious places like that?

AC: I just think they have no idea even the process.

VG: Film critics have said that. Female feminist critics from the, let's say, the more liberal circles –the L.A. Weekly, the L.A. Times – places where you would expect some thought, have diminished my work, which is great: Diminish my work. You don't like the project? You think it failed? Tell why it failed. But to diminish the work on that level is embarrassing. And I don't want the same thing to happen here with this music project, because, so far when I'm talking to journalists about this project, they seem to think that the concept of what we're doing musically is a reaction or some sort of provoking of what else is going on in music, and it's not where I'm coming from as a person. I don't really care what other people are doing, and whether I like it or I don't, is not what leads me to do with what I'm doing. I enjoy being in a group where everybody is really connected and we're not following the protocol, like we're thinking on our own whatever it is. If we feel like making a record, we'll make a record. If we don't, we won't. There's nothing fun for me about playing the same songs every night. There's nothing fun for me in using a musical vocabulary that I'm so familiar with and that isn't better than me. All I'm interested in doing is making things that are more interesting than me and my own vision and my own level of understanding of them. That's the goal here with this project.

AC: So why do you think it is so hard for the media to comprehend that you're touring without some kind of product to sell?

VG: I think they're so caught up in the story, in the old story that they don't understand that the world is on the cusp of a different type of collective conscious ... and it's not me. I'm just the reflection of it; I'm one of many people who feel more open to some other kind of story, just to a new story and not stuck in an old story. I don't know why.

AC: There must be something special about doing something that's alive in that moment, and then you move on to your next concert or project or whatever after that. And the concert here in Austin will most likely be different from any other concert y'all play on the tour.

VG: And yeah, and by the time we're done, the 16th show, shouldn't we have grown? Because we're investing energy in this real openness. The chance of us growing musically is good; the chance is good, it's a good chance. If you look at the Beatles from '64 to '68 and you look at the Chili Peppers from 1990 to 2007, the Peppers are the same cartoon characters, and the Beatles – first of all they produced a ton of work, and they transform politically, aesthetically, their fashion, their diet, their relationships, how they see the world. You know they just grow in so many ways because they're really open-minded, and they're really part of the collective conscious. They're a reflection of everything that's really going on, and it's really beautiful to see creative people growing and changing and modifying and adjusting themselves and being open like that.

AC: So, with your show being held in a movie theatre here, do you have any plans for any type of visual performance to go along with your music?

VG: No, the concept is – well, first of all, I just love movie theatres, and so I was very excited that we booked that particular show, and we booked a couple of other movie theatres on the tour. I prefer a sit-down venue, because I think to sit down and watch a band is so beautiful, unless it's the kind of band that's rocking the house in some form. But if it's the kind of music that's a little more thoughtful and less motivated toward dance or jumping or stage-diving or whatever people do, then to sit down at a venue where, not only you're seated but you can see, where everybody has at least an adequate seat. In a movie theatre, everybody's set up so that they can see the bottom of the frame, and that's really important to me, because some of us will be on the ground when we're performing and stuff, and I want to have that ...

AC: Vantage point?

VG: Yeah, I want to have that comfort and focus. At least give the people in the audience the potential for comfort and focus, and if things are going really well onstage, that whole connection could be really beautiful.

AC: So you've said this isn't improvising so much as composing live onstage? How do you and your bandmates communicate, and how do y'all know where the piece will be heading?

VG: Well, what most people do in improvisation is they have a music form – whether it's jazz, whether it's blues-based ... even if they're in a noise band. They have a sort of vocabulary that they stick to, and then improvisation is a way of soloing or meandering around that musical vocabulary in ways that are somewhat self-indulgent – self-indulgent or self-gratifying – to each musician individually, and they're sort of exchanging those things together. So what we're doing is not that. We're remaining extremely conscious, because when you improvise like that, in a sense you go unconscious. You go to your emotional life, not to your thoughts as much, and what we do is we remain conscious, so we're constantly listening to the compositions, and we're adding and building on the compositions so that we're creating movement within those compositions, and we rely on those movements for long periods of time. They may repeat for long periods of time before they morph into something else, into another movement. So we're performing, but we're listening carefully to each other's exchange and playing, and we're manipulating that or moving toward things that are compositional. If I told you that these pieces were prewritten, you would not question that. So if you hear the show, you know, and you were not told that we improvise the show, it wouldn't be apparent because we're not – it doesn't feel like that; we're being so conscious and so focused that we're careful not to go off into music cliché or into disconnection in any way, you know? We tend to stay very connected, so it doesn't appear like that. It does, however, come from let's say musical vocabularies that are changing or certainly beyond ourselves. They're past our, our level of understanding; they're better than us.

AC: Do y'all have a skeletal idea of these songs before the concerts?

VG: No, nothing like that at all.

AC: Nothing at all?

VG: No, because then in a sense we have a frame or an idea formed. ... When you go up there in front of people, you know you're in performance mode, and so there's a level of focus and concentration, and if you accept that, you become extremely conscious in that moment. If you go up there, and you battle your way out of that to where you create something that's pleasing for yourself onstage, and you start to hear the composition's form – you can listen for them. We're all connected; the energy of the world is all connected. As much as things come from you, they're also out there; they're out there in the world. And so you're just identifying them. And the more you've done that in your life, the easier it is for you to identify them and to bring them in to control those energies. So you just go out there, and you start to play, and you start to listen for those compositions, which are larger than life. They're bigger than me and Eric and Nikki and Rebecca; they're bigger than us. We're all just there listening and being part of their formation.

AC: A conduit?

VG: Yeah, in a sense. I mean, it's coming from me, yeah. It's coming from Eric, yeah, but it's coming from us listening, too. It has its own power. Just like a movie does. I used to tell people this all the time when we go on set. You know, it's like the film is bigger than all of us; the film is doing this; it's got its own life. If you overwhelm that life with your own ego and your own self-glorification and this idea that you're in control of it, you're nothing, man. ... I don't care how fucking smart or interesting you are, if your work isn't smarter and more interesting than you, then it's nothing. It's nothing. It's gotta be better than me; it's gotta be more interesting than me. I'm a buffoon. You know what I mean?

AC: I hear ya. So do you have any plans for any film projects currently?

VG: I have no plans at all in that way.

AC: So you're just not looking past RRIICCEE right now?

VG: Yeah. I'm really deeply involved in this project, and I mean this with all my heart. ... If we collectively –the four of us – can get to the place that I see, or let's say when we get there, I think it will be a reflection of some of the best work of my life, if not the best work that I've ever been involved in. So, you know, this is not a side project or a piece that I'm doing while I'm waiting to direct another movie. I can direct another movie anytime I want. In spite of the bad reviews of me as a person and The Brown Bunny, the film made a lot of money, and I can make another movie anytime I want, certainly in the budget that I make films, anyway. I can pay for them myself. So this piece – if I didn't feel that this would be some of the most exciting, interesting work that I did, then I wouldn't be involved. I don't think I've ever done anything sort of half-baked or to occupy my time before, because my time is extremely occupied with my hobbies, you know, so this stuff only takes me out of my life. I'm antagonized by the desire to do something, and it pulls me away from my comfort. This isn't like for fun or anything, there's nothing fun anyway because I'm so controlling, and I'm such a maniac about the details of everything. Fun is like jerking off or eating chips and dips in bed, or something. Fun is this whole other thing for me. It's not going from venue to venue perfecting the sound and getting everything perfect and trying to play the best show and organize the guys in the band and deal with all the stuff. It's interesting; it's engaging. It's not being done because I have nothing else to do. And no, I'm not thinking about films at all.