Think Outside the Book

Eric Schlosser on Richard Linklater's adaptation of his 'Fast Food Nation'

By Wayne Alan Brenner, Fri., Nov. 17, 2006

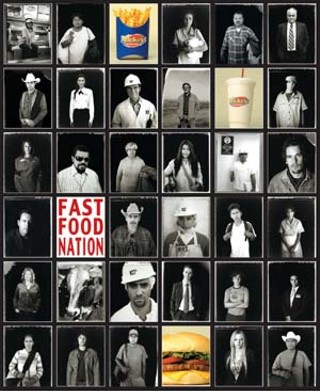

Eric Schlosser's 2001 bestseller, Fast Food Nation – an extensively researched exposé of this country's fast-food industry and its societal and economic impact – was expanded from the author's earlier articles for Rolling Stone. It has now been expanded into a film – a fictional and multipartite narrative that highlights the lives of diverse characters who affect and are affected by the industry – by Richard Linklater. A marketing executive for a fast-food burger empire, a family of illegal immigrants, a retired cattle rancher, an impromptu gang of rebellious teens: These are the human faces through which the film's intent is expressed. Recently, Schlosser discussed with the Chronicle his involvement with the film and what it's like being on the receiving end of institutional ire.

Austin Chronicle: Is this the first time that a written work of yours has been turned into a movie?

Eric Schlosser: It's the first time that it's been turned into a fictional film. An article that I wrote for The Atlantic Monthly about marijuana, which was the basis for my book Reefer Madness, was made into a documentary. That's the only other adaptation.

AC: What was the reason to make Fast Food Nation fictional, when it seemed to be such good material for a straight documentary?

ES: Well, this could have been a disastrously, stupidly bad idea for a film, and I don't think it turned out that way. But it certainly isn't an obvious thing to do, to make it fictional. In the year or so after the book came out, I was approached by many documentary filmmakers, and I really wanted a documentary based on the book. But I ultimately didn't trust any of the arrangements that were being presented to me. So, rather than winding up with something that I felt was a watered-down version or a compromised version, I decided that there shouldn't be any film based on the book. I mean, I liked the filmmakers, but I just didn't trust who was behind them.

Around that period, I met with a British producer, Jeremy Thomas, who is a real independent producer, one of the last independents. And he was interested in a fictional adaptation. And I was on a book tour in Austin, and I met Rick Linklater, and we started talking about a fictional adaptation, and we thought it was an interesting idea. But I didn't sign over the rights to the book for another two years. Rick and I would meet every now and then, and we'd talk about it. We had this idea of taking the title of the book and some of the themes and just situating the whole thing in the lives of characters in a little town. But it wasn't until there was enough of an idea there, until Rick was guaranteed total creative control and there was financing that was going to be completely outside the Hollywood system, that I agreed to sign over the rights to the book.

So, I must have met Rick in 2002, and we talked and worked on it for a couple of years before I signed on the dotted line. He's one of my favorite directors, so any adaptation of his of the book would have been fine with me. Film is very much a director's medium, and I would've been glad to give him the book and just show up at the theatre and see the film. I wound up being much more involved in it than I thought I was going to be. But it was really to help get Rick's vision of the subject on the screen.

AC: Besides co-writing the screenplay, what other input did you have?

ES: When Rick and I decided that we were really going to try to do this, I brought him to Colorado. I introduced him to ranchers. We drove around; we looked at what was happening there. I brought him into the slaughterhouse. And we just spent a lot of time thinking about "Who would these people be? What would their lives be like?" et cetera, et cetera. Make no mistake: This is a Richard Linklater film. But because I'd spent so much time on the subject, I tried to be helpful with what it might contain.

AC: Do you think it's more effective, in getting information disseminated to a bunch of people, to do it in book form or in movie form?

ES: You know, I can only speak for myself. I am a writer. I believe in the word on the page, and I believe in books. There's no one way to do things. I started out as a playwright, then I was a novelist, then I actually worked for a film company in New York; I was a screenwriter before I was a journalist. And for people who really love filmmaking, film is the right medium. For me, I love writing, so I'm committed to writing books. Sometimes when a film is made from a book, it's a horrible thing; it would be better that no film would ever be made. So, once Rick really decided to do this, I slept soundly at night. When you have somebody whose work you respect making a film based on your own work – that's how it should be.

AC: I understand that when you all were filming, you had to go under a code name for the movie. How did that work?

ES: I think it was a combination of things. In general with my work, the less you talk about it, the better you can do it. So there really wasn't an effort to publicize the film as it was being shot. The other part of it was that this was very low-budget with a very tight shooting schedule, and the food industry is very tough and very mean, and Rick just didn't want anyone tampering with the production or trying to shut it down. So it was being shot under the name Coyote. And I think there was an article in the paper here [Austin American-Statesman], that was picked up by The New York Times, that said we were using that name. And I think Rick lost one or two locations as a result. And it was because of the industry pressure, because these are very tough big boys.

The point was to get the film made and not to have lots of publicity and reporters on the set or anything like that. But the scenes that were needed were shot, and it all went smoothly.

AC: Speaking of the industry, what do you think of their Best Food Nation Web site?

ES: Well, you talk about my work as a work of nonfiction being turned into fiction; I think there's another work of fiction for you. I mean, what I like about it is that all of the groups who put up money for it are openly associated with it. You can look through the roster of groups, and it's every major Ag-industry lobbying group that there is – and they're putting their own names on it. So, I disagree with what it says, and I think some of it is factually inaccurate, but at least it's openly linked to who's doing it. ... The Best Food Nation Web site is what it is. People should read it. People should see who is paying for it. And then make up their own minds.

AC: In the fast-food industry, the process starts off with an individual cow or a herd of cows somewhere, and then, through various methods, those cows are turned into little pink uniform pucks. And then those millions of pink cow-pucks are spread out across the nation for people to consume. Does that resonate at all with the idea of turning a text into a film?

Fast Food Nation: A Photo Exhibit

Portraits by Matt Lankes

Through Nov. 30

Intercontinental Stephen F. Austin Hotel (701 Congress; second-floor mezzanine)

Free

ES: No. No. Because that little pink puck, a typical fast-food hamburger patty, has pieces of thousands of different cattle in it from as many as five different countries. And I would say that thing's an industrial commodity, mass-produced, with no authenticity or integrity to it whatsoever. The only similarity is that you have to make a lot of prints of a film in order to have lots of people see it in different movie theatres.

The film that Rick made is his vision. It's his creation. It wasn't created by committee; it wasn't created with the intention of selling as many as possible. I really hope that people go to see it, but this film is not a sugar pill. It wasn't designed to make you feel good; there's no pop soundtrack full of hit songs to sell soundtrack albums. I would say it's the antithesis of the fast-food process. I would say, if you were talking to me about taking that one cow and cutting it up and making a great pot roast out of it, well, that's something that is authentic and legitimate. But making it into a frozen fast-food hamburger patty with a thousand other cows, it's just a different thing.

AC: Are you a vegetarian?

ES: No.

AC: Do you ever eat at fast-food places?

ES: I eat at In-N-Out Burger in California, at Burgerville in Washington and Oregon. These are chains where they treat the workers well; they're paying good wages; they're using fresh ingredients. I went to a restaurant here last night – P. Terry's – which is a hamburger stand that's trying to do things the right way. The food that I eat is not really that much different from what I was eating 10 years ago. But I just don't ever go to the mainstream fast-food restaurants – because I don't want to give them my money. And it's not about "What's the food gonna do to me?" It's about what these companies are doing to everyone else. And I don't want to give them a penny.

AC: Not to feed you only things that you'd like to eat, but in doing research on the Web for this interview, I found nothing that actually refutes what you have to say. I saw that the industry people writing these things would say "What Schlosser is saying is misleading, it's misinformation," like a mantra, but they didn't get specific. And then they'd be like, "And look what we're doing over here," without addressing any of the points you made.

ES: On Best Food Nation, I was shown that there are some arguments with statistics in my book, but it's total distortion. One of the things they say is that meatpacking isn't that dangerous of a job, and that the number of injuries has dropped 50 percent. But the reason that the number of injuries has dropped so drastically is that, in 2003, the Bush administration introduced, through OSHA, a new injury-report form. And entire categories of injuries that were reported 10 to 15 years ago were no longer reported. And so, by changing the form, they cut the injury rate by 50 percent.

Now, the Bureau of Labor Statistics is honest enough that, when they put out their press release about meatpacking injuries, they said that injuries in 2003 cannot be compared to any other year due to the new reporting characteristics. The American Meat Institute, though, if you want to download a great piece of propaganda, they have a pamphlet they put out to honor the 100th anniversary of Upton Sinclair's The Jungle. It's called "Upton Sinclair Would Be Amazed!" and it's all about how Sinclair would be amazed at how great things are in the meatpacking industry. And they talk in that pamphlet about how the injury rate's dropped 50 percent, and they have this chart that shows the rate declining, and no where do they mention that the only thing that's changed is a piece of paper.

AC: So, Fast Food Nation is an attempt to address that sort of thing?

ES: The film is trying to make people confront the reality of what's happening in this country right now, in a way that films rarely do, And certainly in a way that television almost never does. And it's about the fast-food industry and the meatpacking industry on the surface, but it's really about this country. It's just one way of looking at this country, and I hope it opens people's eyes. ![]()

Fast Food Nation opens in Austin on Friday, Nov. 17. For a review and showtimes, see Film Listings.