Expanding Cinema

Avant-Garde Artist Michael Snow

By Athina Rachel Tsangari, Fri., Sept. 17, 1999

No artist could be more perfect to inaugurate "Expanding Cinema" -- the Austin Film Society's avant-garde film and video survey which kicks off during this month's fourth Cinematexas International Short Film Festival -- than legendary Canadian filmmaker and musician Michael Snow. For no one expands quite like Michael Snow. For more than 40 years now, he has surveyed the terrain of life and its representation in every possible medium: painting, music, photography, holography, sculpture, video and sound installation, language, impromptu poetry, celluloid, and digital. Every single one of his artistic processes has revolutionized, and stretched to its limits, the medium he has employed. His film New York Eye and Ear Control (1964) was pivotal in the evolution of free jazz. Wavelength (1967), a continuous 45-minute zoom in a New York loft, is the watermark of structuralist cinema. La Région Centrale (1971), a three-hour-long 360° pan across a vast mountain range, is probably the most gigantic landscape film ever made. The epic Rameau's Nephew (1974) is arguably the most rigorous sound film ever made. The CCMC, Snow's music trio, is a pioneer in New Music, shifting while subverting the old school of free improvisation. This continuity, simultaneity, and almost scientific experimentation that characterizes his body of work is what assures his position as one of the immortals of the international avant-garde. The following is a brief excerpt of a recent two-hour conversation via telephone.

Austin Chronicle: You started your career as a painter. How did you make the transition from painting to avant-garde film and later on to experimental music?

Michael Snow: Before I went to New York in 1963 I was playing piano in jazz orchestras professionally, and I was also painting. I've been continuously doing visual, gallery work, painting, installations, sculpture, photography since 1962. There hasn't been a transition from one to another; I've continued them all. I started playing music when music was invented. I'm really ancient! (laughs)

AC: From early on, your work seems to be preoccupied with the element of time.

MS: I've always been interested in variations. Between '61 and '67, in pretty much every possible medium and material, I used the same subject, the cut-out silhouette of a walking woman (it's called "Walking Woman Works"). Through this process of experimenting with variations of two-dimensional surface, I became interested in the idea of a series of variations presented in time, rather than in space, one after another, which is exactly what the film frames do. That's how I arrived to New York Eye and Ear Control [NYE&EC] in '63. Its title also implies a simultaneity between image and sound. Music is not only used as a way to tell you that this is sad, or this is happy, as it's used in narrative films. I always disliked that. In my films I've tried to give the sound a more pure and equal position in relation to the picture.

AC: The soundtrack for NYE&EC is pretty legendary in the world of free jazz.

MS: Oh yes, it's by one of the most amazing free jazz groups. It's Albert Ayler, Don Cherry, Roswell Rudd, John Tchicai, Sunny Murray, and Gary Peacock. I had just come across the music of these people, and I was completely knocked out. I had arrived in New York two years before, hoping that I was going to stop playing music and make it as a visual artist, try to get gallery shows and all that, which I did do. But running across all that music that was going on in New York at the time changed my plans! For me, there was an immediate connection between free jazz and New Orleans jazz, in which I had been previously involved, playing Louis Armstrong, Hot Five. But the point that I'd like to make is that, although I was very affected by all these great players, after a while I felt some differences of opinion with what they were doing in their sessions. They [the NYE&EC musicians] all used to play "heads," you know, a tune of some kind, and then a solo, and then "head" again, and I found myself disagreeing with that. When I had them come to the studio to record the soundtrack, I was careful to tell them that I didn't want any themes, but as much as possible ensemble playing. They accepted and they performed this way, but, in my opinion, this is one reason for which the music is so great. I mean, they're great, fantastic musicians, but they were stuck in that business of the statement of theme, alternating with solos. That's when I started working on my own music, which is what you'll hear with my trio, CCMC. Hmm, see, this is what happens, everything gets confused in these interviews!

AC: We can't really talk about your films unless we talk about your music and vice versa.

MS: True. Then perhaps we should talk about CCMC now? See, CCMC as a group has existed since 1974 having gone through many member changes. This crew is its current manifestation. Its philosophy from the beginning has been totally spontaneous composition.

AC: What does it mean?

MS: It means making it up as you go along. Or are you asking what does CCMC mean?

AC: That, too.

MC: Well, it could be many things. It could be "Cynthia Can't Marry Chuck." Another one is "Champagne, Chablis, Milk, Cognac." [laughs]

AC: Do you have another one?

MS: Oh, there's thousands of them. Let's see -- "Canadian Men Catholics' Choir."

AC: Are you Catholic?

MS: No.

AC: Are you religious?

MS: No.

AC: Do you believe in anything?

MS: Anything. Yes, I believe in anything [pause, laugh].

AC: Could you perhaps describe how you work during your sessions?

MS: We just play. There is never any prior arrangement. The music comes out of the interaction of the players with the performance space; it makes it impossible to be repeated anywhere else. One of the most wonderful things about music is that it always is of the moment.

AC: Are there lines of communication between you three?

MS: We do listen to each other [laughs]. But there can be a kind of competition, too, between the musicians, besides cooperation. It can very

well be a simultaneity of three minds going their own way at once. But I sometimes find cooperation to be boring, because you end up reaching for stereotypes.

AC: What's the reaction of the audience to CCMC?

MS: The audiences for New Music, like the ones of the so-called experimental film, are small. In a way it's a shame, and in another way, it really doesn't matter because there is a serious audience and there are many serious musicians who listen, too. We all listen to each other. Same with my films. I've been making films for 40 years now which your average cinema devotee might not know because they don't exist in theatres or on TV. But they do get shown in some selected places in the U.S. and then all over the world, Europe, Japan, etc., and I'm happy to keep doing what I'm doing. Like, for example, I'm really pleased about Cinematexas. It's so wonderful, especially since you decided to show Rameau's Nephew, which is four-and-a-half hours long, as you know. It doesn't get shown quite that often [laughs].

AC: Would you like to speak about Rameau's Nephew a bit?

MS: The realism of fiction films succeeds because of the unity of sync sound and the image. You take for granted that the mouths open and these words come out; you think that the person is speaking. The fact of the matter is that the mouth is not speaking. The sound is coming out of a loudspeaker somewhere. And the other fact is that in making a film, the sound and the image are separate. There is an abstraction involved. In making Rameau's Nephew, I was trying to make it experienceable that the voices you hear coming from the loudspeakers are not voices but representations of voices. Even though there is a kind of of realism, where you do believe in the image, and you do believe in the sound, you see that it is actually colored light projected on a flat surface -- the image. And that the sound is in fact something that has gone through a process, so that it resembles human speech.

AC: Why four hours long?

MS: Well, it just took a long time to say what needed to be said. There're something like 30 different sections. Each scene has people in it, and I experimented with the different ways of getting the words out of their mouths.

AC: You persistently try to have the audience confront cinema as an apparatus.

MS: That's really true. What I've been trying to do is not so much comment on life, but to add to it something that has never been experienced before.

AC: What do you think the audience gets out of this experience?

MS: Well, sometimes they get out of the theatre! [laughs]

AC: How do you feel when that happens?

MS: I'm always a bit disappointed. I've seen a range of reactions. Riots, for example. In one case people tried to rip the screen down!

AC: You know that in the Cinematexas screening of Rameau's Nephew, we aren't going to charge admission, but the ones who leave before the end have to pay as they exit?

MS: Yeah, it's really good! I had never thought of that -- I did think of clamps on the seats. [laughs]. The problem is that many people don't stay until the end because all the best stuff is in the end. The last hour is really great!

AC: Would you call your films "cinema of endurance"?

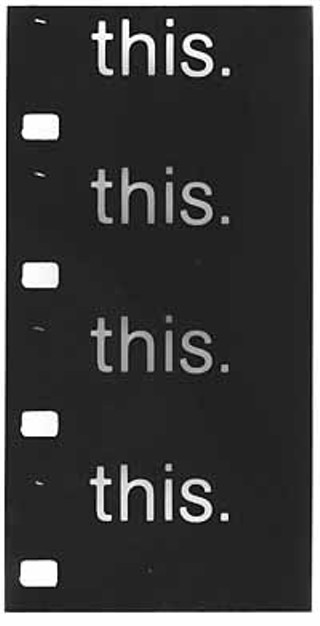

MS: No. So Is This, another film that you're showing at Cinematexas, works purely by controlling the time by which you see something, by bringing in reading. The whole film is built around the word "this," which is used in infinite ways. It sometimes means "this screen" or "this film" or "this word on the screen." "This" is the most present word there is, which puts the spectator in the now, in the present tense of the viewing experience. There is a kind of conversation between the screen and the spectators. It's so unusual for people to read together!

AC: What about Seated Figures, the fourth film you're showing here?

MS: It's all built on continuous tracking. In a way, it's a history of roads, because it starts with asphalt, it moves to gravel and dirt, and it ends up in a field of flowers, like the return to Eden. One of the seated figures is the driver who moves the vehicle for the tracking shots, and the other seated figures are the audience; the two poles of movement and stasis.

AC: The film critic P. Adams Sitney called you a "structuralist" back in the Sixties after he saw Wavelength, one of the most pivotal and breakthrough films in the history of the avant-garde. Do you consider yourself a structuralist?

MS: Gee, I don't know. I'm not sure what to say, because I'm not sure I know what that means. ![]()

Seated Figures, So Is This, and Rameau's Nephew are showing as part of the Cinematexas Festival, presented by the Austin Film Society . Michael Snow will also perform with his trio, CCMC, co-presented by Austin Eye and Ear (the music showcase of Cinematexas) and Epistrophy Arts. See sidebar for details. Call AFS at 322-0145 for film information; for music & ticket info, call Cinematexas at 471-6497.

Athina Rachel Tsangari is the artistic director of the Cinematexas International Short Film Festival as well as a filmmaker and University of Texas RTF lecturer.