A Declaration of Independence

Zavala Elementary and Principal Sean Fox are succeeding at going their own way

By Richard Whittaker, Fri., May 9, 2014

Principal Sean Fox was faced with an emotional quandary. The previous week, a student stole a book from the library at Zavala Elementary. "It was a big deal," he said. "Normally, it's either candy or money."

Zavala is, in many ways, an average East Austin elementary campus, and that means that it labors under the misapprehension that it's inevitably academically cursed. That missing book was a sign that something is changing. In fact, over the last couple of years, the campus has seen double-digit improvements in test results. "We're on an upward slope," said Fox. "All of our scores went up in every subject area." So what magical change did he implement? "We stopped teaching to the test."

In person, Fox doesn't necessarily have the easy-going demeanor you might expect of an elementary principal. Tall, soft-spoken, with the harried, tired look of a man who takes his work quite seriously, he comes across as almost shy. He was already a veteran of East Austin schools when he arrived at Zavala in the spring of 2010. A Corpus Christi native and UT-Austin graduate, he's spent his entire professional career in the often troubled Eastside Memorial Vertical Team: first as a special-ed teacher at Brooke Elementary, then a math teacher at Allan, before returning to Brooke as its assistant principal. At Zavala, his job isn't just to keep the campus open and make sure it doesn't get caught in the state's accountability tripwires. It's to make sure the kids here are really educated, really prepared to move on and learn and thrive. He said, "What kind of principal would I be in this part of town, if I didn't feel like I was coming to work to do the right thing?"

During the last two years, he's made a series of changes. None are radical or revolutionary, but the combination seems to be doing something special. It is all part of Fox's ethos of teaching kids what they need to know, not just what the test asks, and it seems to be working. The numbers speak for themselves. Between 2012 and 2013, the percentage of students passing STAAR statewide in all subjects at Level II or above stayed static at 77%. AISD saw a slight rise from 77% to 78%. Zavala jumped from 74% to 81%. It was the same across the board: reading, up 12 percentage points; writing and math, both up 6%; and science a slight 1% nudge up. Moreover, the community is quietly optimistic that this year's numbers will continue to show improvement. Yet there are also other, more subtle metrics. In his first year at Zavala, Fox dealt with around 250 office referrals. Now it's down to a tenth of that. He said, "There's a whole lot of encouraging, so the pride and the self-esteem of the kids is evident on a day-to-day basis."

Overcoming Contradictions

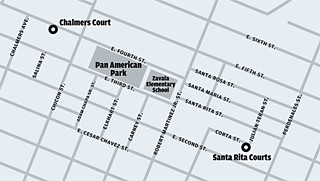

It's something the surrounding Holly neighborhood can be proud of, in this epitome of a historic Austin neighborhood school. But sometimes history is ugly. Outside the front door, there's a National Register of Historic Places marker, and the sign politely but pointedly explains the campus' ethnic history. This was officially the "Mexican school," built to get the Spanish-speaking kids out of Metz and onto their own campus. "This school was built to segregate," said Fox. Named after Lorenzo de Zavala, the only Mexican native to sign the Texas Declaration of Independence, it opened in 1936. "Same year as the UT Tower," said Fox.

Two years later, the school's architects, Giesecke and Harris, and the same construction firm, Falbo and Sons, were charged with building the nation's first Public Works Authority housing project, Santa Rita Courts, to the east, then a year later, Chalmers Court to the west. Again, racial segregation played a distinct role: Santa Rita was for Zavala's Hispanic kids, Chalmers Court was for the white kids attending Metz. A mile away, the African-American kids were housed in the Rosewood project. All that neighborhood history is built into the school's bricks. As Fox walks around his campus, he points out construction lines in the walls: a new gym and cafeteria in 1939, major classroom additions in 1947 to handle the incoming post-war baby boomers, and more in the Nineties, in the economic flare of the tech bubble.

In some ways, it's a campus of contradictions. This is still one of the poorest neighborhoods in town, literally in the shadow of the projects and across from a metal works, but Congressman Lloyd Doggett and former Governor Mark White both sent their kids here. Yet the history of segregation still shapes the campus. The students are primarily minorities (82% Hispanic, 14% African-American), more than a third are either bilingual or speak Spanish as their first language, and 97% come from an economically disadvantaged home. Fox pointed to the public housing projects that flank the school. "That's where the majority of our kids live," he said, and perhaps surprisingly, that's a major boon: Unlike many AISD campuses in low-income neighborhoods, where high mobility is a constant headache, Zavala knows where its students are coming from. In recent years, its population has dropped – down to half of the roughly 600 students it had last decade – "but we've stabilized," said Fox.

That stability means Fox has had breathing room to make his changes. It all starts with the turn of a page; every morning at 8:30am, every child sits and reads. Just reads. It's mandatory. This isn't just what educators dub D.E.A.R. ("Drop Everything And Read") time, nor is it assigned reading. It's called the Accelerated Reader program. Each student takes an initial diagnostic test to establish his or her reading level. That initial STAR grade (not to be confused with the State of Texas Assessment of Academic Readiness, or STAAR, tests) gives each student a zone of proximal development – basically a point-range guide to their reading skills. Each book in the library has a point score, and as long as it's within that point range, the child should be able to read it without assistance.

That reiteration spills over into the classroom. Unlike so many campuses, where the students are taught to dismantle sample paragraphs again and again, the Zavala kids deal with complete texts. It's like learning to drive and maintain an entire car, rather than just knowing how to change the wiper blades. The teachers chart kids' consumption of books, how quickly they're reading, and – most importantly – their comprehension levels. But what's important to Fox is that they are reading, and want to read. It's made the library the heart of the campus, and so far this school year, more than 9,000 books have been checked out. That's on a campus of 339 kids. How many other schools in Austin can say that their students read 30 books this year that weren't mandated by coursework? Fox said, "They can choose books at their level, and know where to find books that they're interested in, and they're just flying off the shelves."

Spreading Success

There are additional incentives for kids to push themselves, like bi-monthly field trips for the kids who make the most progress. Assistant Principal Nicole Anderson said, "For the first nine weeks, we went to the Formula One track and had a behind-the-scenes tour. For the second nine weeks, we went to BookPeople and they had a famous reader read to them, and they got vouchers." Importantly, the system doesn't distinguish between kids at differing reading levels. Anderson said, "Even if you have a struggling reader or a special-ed student, they can still be successful on this program, because they're able to read books within their zone, and they can still earn points."

And it's not just about individual students. Every Monday morning, Fox announces which class made the greatest improvements from the previous week. "This week, we had the most ever," he said. "A five-way tie, out of 10 classes, 100% of students had passed their tests." At the end of the year, there's the community reading rally. It's a neighborhood tradition that precedes Fox's tenure by two decades, with high-profile guests (for this year's event, held last weekend, Texas Education Commissioner Michael Williams was on hand to read to the kids.) The UT band and UT cheerleaders perform, and there's a special treat for the top readers, in a carnival atmosphere. Fox's face cracks into a smile. "Last year I got a pie in my face."

Anderson laughs. "You got 25 pies in your face."

Fox makes that serious face again. "Whatever it takes to get a kid to pick up a book and start reading."

The Accelerated Reader program was just one part of the changes that Fox instituted. Multiplication tables are back in the math classroom. He's also had teachers become subject specialists starting with the third grade – not unusual in primary education, but new at Zavala. Now students split their days between different classrooms, learning personal responsibility and preparing for middle school. Yet it also helps the teachers, especially in lesson prep. Rather than struggling to become an expert in every field, Anderson said, "Instead now, it's 'OK, I'm the math teacher, and I can really differentiate my special-ed learners from my English-language learners from my students who are struggling.'"

Test-Prep vs. Education

So if Fox has stopped teaching to the test, here's the $64,000 question: What is "teaching to the test"?

In some ways, it's less a single defined set of actions, and more a mindset. No Child Left Behind, the decadelong federal program, raised the stakes to perform on tests, and schools quickly realized that there were certain key words in the questions. Fox said, "It's like breaking a code, and you see scores go up. Kids can see the word 'difference,' know to subtract, know how to eliminate answers, and all of a sudden, the gap was closing. Was it really closing? No. We were showing an illusion that it was."

Fox calls it "pseudo-education," and it's a rabbit hole that's swallowed many schools. They're so terrified of being caught out in punitive accountability systems that they do only what's needed to get kids through the tests, rather than provide a rounded education. As the number and importance of the tests increases, the amount of time on test-prep increases; the depth of children's knowledge and learning skills suffers. Yet on the end-of-year reports churned out by the Texas Education Agency and the federal Department of Education, everything looks great, and pro-testing groups like the Texas Small Business Association and the Greater Austin Chamber of Commerce applaud the results. Then kids enter the workforce, and those same pro-testing groups complain that their new employees have no applicable life skills. Anderson said, "It's a false celebration, when you're telling people that these kids can pass the test, but the bottom line is that all these teachers know and that child knows: 'Oh, wow, I don't really know how to read.'"

It's not just how kids are taught, but what they are taught, and that's a particular issue on elementary campuses, where teachers are expected to be generalists. Fox said, "You would start the year off teaching all your content areas. As the pressures begin to increase with the test, you tend to put more emphasis on reading and math, because that's what you're being assessed on that year, and writing and science start to dwindle."

The breaking point for Fox was 2012, the last year of the old TAKS (Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills) tests. He'd already seen students lose their love of reading, and teachers not wanting to teach it, and that was only going to get worse with the longer, timed STAAR. He and Anderson sat down and brainstormed, but finally realized: The answer was simple. Get them reading more. Not just in the classroom – in fact, maybe not even in the classroom. And not just passages that they'll be tested on, but complete books. He recalled gathering his staff and telling them, "'We're not going to teach kids to read using test prep passages.' They got excited and started clapping. ... I could tell by the looks in their eyes that a weight was lifted off, and this was something they were going to pour their hearts and souls into, to get results."

Getting the teachers on board was easy. The tough part was telling the district – and Fox wasn't exactly going to run to the Carruth Administration Center, yelling that he was re-inventing the wheel. He said, "If you go and you communicate like that, you get put under a microscope by everybody. By the community, by your teachers, by all the stakeholders." Instead, he put the pieces together and just got it done. He said, "It's kind of like Coach Strong said. You'll bring people on board when you start winning. Either I'm going to win or I'm going to lose. Either it's, 'See you later,' or I'm going to win and bring people on board."

Chickens and Day Care

If you're looking for a concrete example of Fox's ability to slip under the district's radar, it's in the small patch of open land at the center of Zavala. Sheltered from prying eyes, for years it was a nighttime retreat for drug users and the homeless. Fox said, "When I first came here, it was just bare dirt, where you would regularly find needles and condoms and f-words on the wall." The first step was simple: getting the district to enclose the area with a security fence. Ever since then, there has been no graffiti and no trash. Fox smiles. "The secret is that sign that says 'You're on video.'" But he wasn't just cleaning up the square to clean it up. By adding that fence, and working with volunteers, Fox created an inner-city wildlife lab. He said, "The goal was sustainability. A place where kids could come and learn about nature." Now that unruly slab is a nationally certified wildlife habitat garden, filled with natural plants and wildlife and even a chicken coop. "Chickens are great animals to teach life cycles," Fox said. "They grow up pretty fast and lay eggs."

That's not the only nurturing environment that Fox helped build. Last year, the school lost teachers only because of centrally mandated staff cuts. Well, except one, who left because she was commuting daily from Pflugerville and had childcare issues, and even that's an issue that Fox is tackling. Elementary school teachers tend to be younger, and often thinking about having kids of their own. Fox opened a staff nursery, so staff wouldn't have to worry about their own children while they're educating other people's. There's around eight or nine kids there, with another couple of staff expecting. It's not an indulgence. He said, "If we didn't have that day care, we would have lost good, good people."

"Teachers stay here," said Anderson. "It's part of what makes this school great." She credits the culture of learning and optimism that Fox has nurtured for that retention. "If people don't believe in the mission of the school, they're out of there."

A Community in School

It's teachers like Gina Ozuna who are doing the heavy lifting to enact Fox's changes. She joined Zavala straight of out of college, 12 years ago, as a bilingual third-grade teacher, in a classroom where most kids spoke Spanish as their first language. "Testing has taken a huge toll on our students," she said. "They're discouraged, and they see school a little differently because of the test." Now, in her the fifth-grade reading class, her students deal with what she called "authentic literature" – whole books or articles from publications like Time for Kids, rather than just select passages. Currently, they're reading in the social studies curriculum on the Westward Expansion. She said, "The first week we got back was poetry, so I found poems on Lewis and Clark and the Trail of Tears. Then we had drama, so I found a play on Lewis and Clark and a play on the Trail of Tears. Then last week was myths and folk tales, so I found some tall tales from that time. So they're finding there're different forms of genre, but it's still the same topic." The problems they solve are still drawn from the state-issued Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills standards, but "the questions that I give them are more analytical, higher thinking."

It's a slightly different story in Cheryl Gibson's fifth-grade science and math classroom down the corridor. "I don't even have a textbook," she said. "I'm doing labs every day." In her 30 years at Zavala, she's seen it all. She taught Doggett and White's kids, she's outlasted untold administrators, and she's been through her fair share of campus reforms, including just about every significant reform in testing, an alphabet soup of acronyms that shifted from TEAMS to TAAS to TAKS to STAAR. In the early days, they were a boon to education in Texas, making teaching "more refined. ... When I first got here, you were teaching whatever you felt like teaching. Yeah, stuff came down, but you could say, 'I don't like chemistry, so I'll take more time teaching the stuff that I like.' Once we started getting testing, we started getting the objectives and TEKS, we weren't just giving kids whatever we felt like, so the kids were getting more rounded." That's part of what she likes about Fox's approach of dedicated subjects. The kids get more rounded, but the teachers get more specialized. "You become an expert in that subject, as opposed to a little bit of everything."

But the process doesn't stop at the classroom door, nor does the need. And it's not just reading. East Austin may be gentrifying, but this is still one of the poorest, most hard-scrabble parts of town, and Zavala has been lucky enough to get dozens of organizations to help out, from the Austin Jazz Workshop volunteering with music classes, to Operation School Bell providing clothing and essential supplies. It's not hard to find a UT student volunteering, while the whole campus has been twinned with Bryker Woods Elementary on a peer-to-peer basis. Zavala was also just selected as one of a handful of AISD schools to partner with the Thinkery children's museum on a new program called Tech Reach, where students in grades 3-5 will learn fundamentals of programming and robotics. (Fox noted, "Communities in Schools is housed in our basement, and that brings in an extra four counselors and social workers that help our kids and help our families get in touch with resources.") But one of the biggest and longest-running partnerships is with the Zavala Circle of Friends.

Involved and Evolved

Formed in the mid-Nineties, it was part of an earlier reading initiative at the school. A teacher from the campus visited the University United Methodist Church Sunday school, looking for volunteers to help with a reading program called Helping One Student to Succeed, or HOSTS. Initially, their purpose was just to help with the extracurricular reading program, but that changed as they realized the bigger underlying issues. Circle member Sandy Smith said, "What initially drew a lot of us to volunteer was the concept of helping one student succeed, but it's evolved into helping one school succeed." Over time, the group has expanded beyond UUMC, adding volunteers from bodies like UT and the YMCA, and meeting once a month with the campus to strategize. Smith said, "What we try to do is listen to the principals and teachers about what they need, and brainstorm about how we can get involved and facilitate it."

Like Ozuna, Smith has seen the deleterious impact of testing. She said, "The students that I was particularly involved with seemed to become more nervous about reading." That why she's optimistic about Fox's approach. "If someone can learn to love to read, all the rest of the stuff can happen, and they'll pass the test. They'll understand paragraph structure and what the main theme is, because they're interested in the story, and not just trying to pick out words because that's what you're supposed to do."

With the shift from the extracurricular Helping One Student to Succeed to the integrated Accelerated Reading program, the Circle's role at Zavala has shifted from tutoring to support. She admits some staff were initially concerned about the use of motivational rewards like trips: Shouldn't kids just want to learn? However, she said, "After implementing it and running it for a couple of years, for this population, it works." Moreover, the rewards aren't about who is best. They're about growth, and the students understand that. She said, "The kids are rewarded not on an absolute measure, but a relative measure. If they make progress, they're rewarded."

Gibson's already seeing that in her science classroom. As part of the reading initiative, she uses flash cards with science terms on one side, and the definitions on the other. The kids only get them when they can correctly describe the back from the front, and vice versa. The bigger the stack of cards, the more the student knows. The cards become a sign of their achievement, not an end in themselves. Gibson said, "The other day, one girl said, 'I alphabetized my cards,' I said, 'You did what?' and she said, 'It took the whole living room floor, but I alphabetized them.'"

Changing the Culture

As you've likely noticed, there's a catch here. All of Fox's reforms, all the books and assistants and volunteers, add up to one thing: a way to circumvent the impetus to teach to the test. He's found a way to get his campus out of the accountability crosshairs, while giving his kids an education that's actually worth something. But the standardized tests are still there – and there are a lot of people asking the same question: Why?

Some days, it really seems like the whole nation is through the looking glass on testing. On April 24, the Texas Education Agency issued a gleeful press release stating that "almost 80 percent of 5th and 8th graders pass on first attempt at STAAR." What that actually means is that more than 20% of fifth- and eighth-graders in Texas face being held back a year unless they pass a retest. That's a retest of a test that an increasing number of academics, experts, and parents strongly believe is actually damaging to the students' education. But then, this is the same state agency that brags that 84% of the class of 2010 graduated on time. Of the remaining 16%, half either came back the next year or left with a GED. That basically means that one in 10 high schoolers are expected to just fall off the grid.

Kids do get through the system. Next year, Austin parent Dineen Majcher will join other proud caregivers when her daughter crosses the stage as part of the high school graduating class of 2015. But as the president of Texans Advocating for Meaningful Student Assessment, she's angry with the process that got her daughter there. She said, "The biggest problem is that it narrows the curriculum, and eliminates the opportunities to have interesting and really engaging instructions."

Like many parents, she was shocked to find out that her daughter's standardized test scores would be part of her final grades. "At first I thought, 'That can't be. Maybe I don't understand, or maybe the teacher doesn't understand.'" Then she and some friends talked to a lawyer they knew, and they said, "No, that's right." "That's what prompted us to pursue things at the Legislature," she said, "and we found parents from around the state who were equally angry and incredulous."

Like Gibson, Majcher's not angry about the existence of tests. She's angry about how they're used, and how little information STAAR really gives parents. If Texas must have testing for young students, she said, it should be diagnostic, not punitive. She said, "TEA has testified in committee that STAAR is not diagnostic. So why are we doing it?" She argues that Texas faces an education time bomb, with an estimated one-fourth of all eligible students set to miss graduation next year because they're struggling with their end-of-course requirements. She doesn't blame the teachers ("They're doing what they're told to do") but instead the high-stakes paradigm that makes everything about the test. She's seen that impetus damage her own daughter's education. Her history teacher had an exercise in which she would assign each child a fictional country to run, and they would game out their interactions through a series of incidents and set events. What they were actually doing was learning concepts of diplomacy and risk and geopolitics. And then the teacher had to stop it. Majcher said, "There was no time for that, because they had to learn the TEKS."

This is one of the rare issues on which left and right, Democratic and Republican voters, are in simple agreement: The era of high-stakes testing has to end. She said, "Parents are fed up with four-hour tests for fourth-graders." She's seeing pressure from parents, both from her group and others, slowly start to spin the wheel down at the Legislature, and believes that canny politicians will see that this is where votes lie. However, it's still a hard slog. "There's a long established culture of testing in Texas," she said, but with grading options like course work and projects gaining traction, lawmakers aren't quite so driven to boil everything down to quantifiable metrics. "The question now is, how do we fix this?"

The political tide may well be turning. Until then, that leaves principals like Fox trying to give kids a meaningful education while still evading the sharks in the high-stakes water. So until the tide turns, isn't the solution to just do what Fox does? Damn the tests, teach old school, and trust that the kids everywhere will get through? Maybe, but not exactly. Fox warned that Zavala's achievement may not be scalable or repeatable, nor are the successes of any other campus. He said, "We have tried to implement what people have done at other schools that has worked well, and we've failed miserably at it." Instead of a one-size-fits-all approach, he says that successful programs must be "very organic. ... We have to really look at where we were, where we are, and where we want to be going. They can't take us and move us over there, and we can't fit into other molds. We can't do exactly what they do and get the exact same results. We have to, as a campus, work together and work as a team. We have to, as a campus, have a culture in which people can brainstorm with each other and come up with ideas and implement those ideas and fail sometimes and learn from our failures and move on together as a family."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.