The Next New Neighborhood

City and residents plan a sustainable Colony Park

By Robyn Ross, Fri., April 4, 2014

Dressed in yellow T-shirts and carrying clipboards, three UT students approached the house on Colony Loop Drive and knocked. A woman peered out the window, then opened the metal bars outside her front door. "We're from the Colony Park Sustainable Community Initiative," one student told her, switching to Spanish when the woman asked.

The young women interviewed their respondent: What were the most important issues facing her neighborhood? How would she rate her access to fresh food? Was she aware that right now, the city was working on a master plan for 208 acres of vacant land a hundred yards from her front door?

A loose dog trotted down the sidewalk. In the yard across the street, two men sat in folding chairs and watched. They had refused to talk to the UT students going door to door administering the survey. The young women jotted notes on their clipboards and moved to the next house.

The door-to-door exercise took place in September, as one of the first efforts to involve neighbors in the plan. The Colony Park initiative – funded by a $3 million grant the city won in 2012 from the Department of Housing and Urban Development's Sustainable Communities program – will result in a shovel-ready master plan for a mixed-use community designed to maximize environmental and social sustainability. By December, the design team, led by Chicago's Farr Associates and local Urban Design Group, will finish a plan for the first phase of the new neighborhood's streets and infrastructure.

On April 14, the design team will present residents of the neighborhoods near the land with a draft of the final plan.

Infilling the Gaps

Like the Mueller development, the project is a rare opportunity to create a brand-new neighborhood from scratch. It's also an opportunity to revive the neighborhoods nearby, where residents struggle with crime and a lack of transportation, retail, and entertainment options. Like any other neighborhood, "we want to be a place of destination rather than a place of exit," says Margarita Decierdo, a member of the "core team" of neighborhood leaders that meets regularly with city staff. "We want to be a place where people can say 'Hey, let's go to the cafe over there at Colony Park, and go to the nice park with the view' – it's not a place you're trying to escape from."

The land to be developed cuts between Colony Park and Lakeside, the two existing neighborhoods most affected by the change. Cedar trees dot the hills that offer views of the distant Downtown skyline. Children cut through the undeveloped land to get to Overton Elementary School, which sits amid roughly 65 acres of dedicated parkland that the plan will design.

The larger area included in the master planning process – the area the UT students canvassed – is a 15-square-mile region bounded by US 290, SH 130 and US 183, and FM 969 (MLK/Webberville Road). Residents from the entire area are invited to participate in the public meetings. Four of the five census tracts in the planning area have median family incomes below the city's average; nearly a quarter of the area's residents are not U.S. citizens.

One of the grant's explicit goals is to bring together different agencies and city departments – including Watershed Protection, Capital Metro, Public Works, Parks and Recreation, and Police – and establish a process for working together on such developments. Last September, representatives from the departments boarded a yellow school bus for a two-hour tour of the larger planning area. As members of the core team narrated the trip, city staff and members of the design team from Chicago and Austin surveyed the landscape. The tour included manufactured housing communities; stretches of rural land punctuated by horse barns; Walter E. Long Park; an urban farm; and a storage yard for portable toilets. In the Lakeside neighborhood, the core team pointed to decrepit duplexes in desperate need of repair.

The region lacks a grocery store, medical facilities, banks, a pharmacy. Even the green space marked "Colony Park" on the map isn't actually a park, but an undeveloped hill. The area's primary amenity is the Turner-Roberts Recreation Center, which reopened last fall after a more than two-year closure. The original building opened in 2008 and closed in 2011 because of structural damage caused by the shifting soil.

A Relationship and a Process

The relationship between the neighborhood and the city has been on shaky ground as well. Longtime residents speak of feeling abandoned by the city, whose Downtown decision-makers seem far away. Early meetings took inventory of the neighborhood's current conditions, and the litany of problems included crime, illegal dumping, lack of code enforcement, and concerns about area schools. The feelings of being ignored were exacerbated when staff from the Neighborhood Housing and Community Development (NHCD) department originally applied for the HUD grant without first involving the neighborhood.

Relations have since improved. The project is "a good thing, but the community knew nothing about it until they got the grant," Colony Park Neighborhood Association president Barbara Scott says. "If they had contacted us before they wrote the grant, maybe the grant could have been written differently to encompass some things that are missing in the area," like funding to help current residents repair their houses.

"We did learn a big lesson by going out for the grant and not letting the community know," says Rebecca Giello, assistant director of NHCD, adding that the process was very competitive and the proposal had to be submitted quickly. "It was not at the disregard of the neighborhood, but it was absolutely an oversight, and we've worked long and hard to put that back on the right track." Giello's office now has weekly three-hour meetings with the neighborhood representatives, whom she credits with "almost every single good idea that's coming out of the planning grant. ... The investment of their time is incredible. We stand somewhat humbled by what this grant has taught us. There's accountability in making sure the community is heard, feels heard, and that they have a seat at the table for all decisions."

The city also replaced its initial plan for the public engagement process with a framework devised by Decierdo and supported by the core team. The new plan partners with UT's Division of Diversity and Community Engagement, and ACC's Social and Behavioral Sciences department and Service Learning and Civic Engagement Office. It enlists students who assist at meetings and do the block-walking to communicate directly with residents. "It's been a good process, and I think it's a process that all city departments need to use," Scott says.

In large public meetings in December and February, the design team presented residents with slides of different types of development and asked them to vote for their favorites via keypad polling. Residents have offered immediate feedback on everything from their top priorities for park amenities (a swimming pool was the big winner) to the length of residential blocks.

At the April 14 event, a giant map of the plan will be spread on the floor of the meeting room, allowing current residents near the plan area to find their houses and follow the proposed streets to the new parks and amenities.

Rising Values ... Rising Costs

The new neighborhood will hew to HUD's environmental principles and will turn some of the land's challenges into opportunities, designer Doug Farr says. The creeks and wetlands that slice through low-lying areas will be preserved as "fingers of nature," and each hilltop will feature a public park.

At the same time that the design aims to create an environmentally sustainable place, it also wants to sustain the community. Existing residents have voiced some concern about the new development potentially raising property taxes and displacing neighbors who can't afford the higher costs.

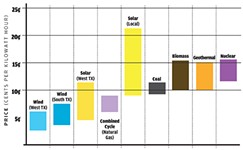

"If we are successful at designing a beautiful place – which is our goal and mandate – it will appreciate," Farr says. "The new stuff we do will hold its value and increase in value; if it's nice, people want it, and they bid it up. The flip side is, that doesn't have to happen to the folks that already have their home." That's the difference between gentrification and displacement, he says. As master planners, he and Urban Design Group's Laura Toups can't mandate that prices and property taxes stay low. But they have identified energy, water, and mobility choices as household budget items their plan could affect. Environmental sustainability – while a "green" end in itself – can also be a tool for curbing displacement. For instance, the city offers conservation rebate programs to help low-income residents retrofit their homes for energy efficiency and lower their bills.

Farr says his team has also looked at ways the plan can lower another family expense: transportation. The Imagine Austin comprehensive plan includes a transit-oriented development on one corner of the project, where one day Capital Metro expects to run the Green Line commuter rail. In the meantime, the new neighborhood's design extends and connects streets that today dead-end at the city's land. The result will be a loop that facilitates better bus service as an interim step toward better transit.

In addition, the design team's research indicates that families in the area have 1.88 cars on average. By building provisions for a shared-car program into the new neighborhood, the team hopes to offer new and existing residents the option of reducing the number of cars they own. Downsizing to one car, Farr says, could save a family several thousand dollars a year – more than the amount their property taxes would increase from elevated property values.

While Colony Park is a master-planned community on city-owned land – like the Mueller neighborhood – the two developments may be more different than similar. First, there's the physical topography. Colony Park is hilly, with shifting soil, in dramatic contrast to the runway flatness of the former airport. The sloping hills present a challenge for building, but Farr says they offer an opportunity, too. "If you have a hill you have a hilltop; if you have a hilltop you have a view of Downtown and you can sell it. You can lay development on a hill and a slope in a way that creates more value than a cost." In fact, the plan residents will review April 14 leaves all hilltops open as public space, inspired by a suggestion a man made at a community meeting to set aside space for watching the sunset.

The locations also are different. Mueller's initial development engine was the tax increment finance zone encompassing its big-box stores along I-35, which helped pay for the neighborhood's early infrastructure. No such opportunity exists for Colony Park, which despite its proximity to US 290 and SH 130 can't compare with Mueller's high-visibility, high-traffic location.

One other key difference: planning for Mueller occurred over 20 years and was initiated by neighbors. The Colony Park process, which began engaging the public last fall, will be finished by December.

Defining 'Affordability'

The two projects diverge even more on questions of affordability. The Austin housing market means Mueller's central location and popularity have pushed most home prices out of reach for people with low-to-moderate incomes. In Colony Park, which is farther from the urban core, home prices are much lower, and the connotations of "affordable housing" are different.

The 208-acre tract was originally going to be turned by a private developer into a low-income trailer park. The city bought the tract in 2001 to circumvent that plan, but at the time designated it for housing for low- or moderate-income residents. "From the very beginning we were opposed to that," Decierdo says; neighborhood leaders wanted a mixed-use, mixed-income development. "We're not necessarily opposed to housing per se, but to come and saturate a community that's already saturated with low-income units is only to perpetuate the poverty that already exists there."

The 78724 zip code already has four tax-credit low-income housing projects, plus poorly maintained private housing owned by absentee landlords. Core team member Melvin Wrenn, who has lived in Colony Park more than 30 years, says the team wants to limit new low-income tax credit housing properties – "which people most often call affordable, and we call slum development" – to 17% of the new neighborhood.

The team is more receptive to including housing that working people with average incomes can afford to buy. "What we are wanting is mixed-income for that area, which means a teacher with a $45,000 salary can afford a house, and somebody who's making more than that can afford a bigger house," Scott says. That vision comports with Farr Associates' goal of providing a diversity of housing types within each block of the new development, each targeting a different life stage and income, so that residents can "age in place" at Colony Park. Wrenn suggests the new development could include starter homes accessible to existing renters, who could buy in the neighborhood. Increasing the percentage of home ownership would help stabilize the area and offer an antidote to crime and code violations, the core team says.

"That's the change we want to bring," Decierdo says. "You bring in higher income individuals that can be part of our community and help us lift it up. We are in need of those individuals who see a place where they can actually live."

Neighbors to Neighbors

On the other side of Loyola Lane from Colony Park, the much newer Agave neighborhood is also involved in the master planning effort. Agave NA president Chasity Larios describes the neighborhood's 400 households as comprised of professors, musicians, chefs, teachers, public employees, and people involved in the tech scene. "We bought here because the area is one of the last affordable places near Downtown with vibrant cultural diversity," she says. Unlike nearby Colony Park, Agave's children are currently zoned to the Manor school district, but many attend the nearby Austin Discovery School charter instead.

Agave residents, she says, are "your quintessential Austinites – they want to see stuff like urban farming, maybe community gardens, a farmers' market, bike lanes, pedestrian lanes, local businesses and retail, a coffee shop." A grocery store and a pharmacy – long desired by the older neighborhoods – would be good too. So would a park or community meeting space, perhaps a facility that could offer after-school arts activities for kids from the whole area. "There are a lot of planning challenges to this area because there's little infrastructure, like bus lines, meeting space, or parks," she says. "We want this whole area to be a cohesive community no matter which neighborhood you live in."

The residents of Agave want to be part of the northeast Austin community, she says, which for many includes becoming part of the Austin Independent School District. "We're very respectful of the Colony Park Neighborhood Association so we want their wishes to be upheld," Larios says, "and I don't think there's anything they've said that we disagree with."

From Here to There

Even if the neighbors agree on their goals, realizing them will still bring challenges. While Toups says vertical construction could start as soon as early 2016, it will be 10 years before the first phase of the neighborhood is built out. And some aspects of the plan could manifest differently than the slides neighbors saw during this year's meetings. For instance, while the process of drafting physical guidelines for street design and building placement are pretty standard, Farr says, there's no accepted process that ensures a developer will offer shared cars. "We can encourage it and show where it makes sense," he says. "You can lead the horse to water, but will the developer that shows up take the opportunity we've created?"

Similarly, the master plan will be "rail ready" and base its transit-oriented development on the Green Line, but the rail line itself is the purview of Capital Metro. "Our plan needs to have a position on what transit needs to do," Farr says, "but it's out of our control. We can state our understanding of a preferred or likely future, and base our plan on that."

And bringing desired commercial development to the area won't be easy, even with its location near major highways. Toups of Urban Design Group says that because the tract is city-owned land, it may be able to offer incentives for amenities and major employers to locate there, "lowering the cost for a business or commercial use to be out here rather than somewhere else that may have a few more rooftops or perceived demand. But it's still going to be a challenge of attracting the amenities that we hear people really want."

Going into the April 14 meeting, the neighborhood core team's mood is cautiously optimistic. "We're cheering for Doug Farr, and like a lot of people, we're going to do everything we can to help," core team member Wrenn says, adding that he feels a mixture of doubt and hope.

"Historically it's been a neighborhood that has been disenfranchised and neglected," Decierdo says. "What we're trying to do is reverse the process so it doesn't remain ignored and isolated, but rather it's a neighborhood that, through this planning process, can become sustainable."

Residents saw three potential plans for the new neighborhood at a February meeting; a draft plan combining preferred elements of all three will be unveiled April 14.

Option 1: Moonrise

All three options place a "town center" on Loyola and a transit-oriented development on the northeast side of the tract. In Moonrise, the big curving drive between the two is the dominant feature, but its potential downside is speeding.

Option 2: Blue Stem

The route from Loyola to the TOD is more roundabout, and the design prioritizes children's safety. Designer Doug Farr says its weakness is that the undeveloped "fingers of nature" may divide the neighborhoods.

Option 3: Five Hills

In this version, the neighborhood centers and parks are oriented to the project area's hilltops. The tradeoff is that the route between the town center and the TOD is not as direct.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.