Science Goes to Court

Death row case sets new state law against prosecutorial resistance

By Jordan Smith, Fri., Nov. 1, 2013

Rigoberto Avila was in the living room of the small two-bedroom apartment on El Paso's west side watching a basketball game on TV when he looked up and saw 4-year-old Dylan Salinas standing in the hallway, looking frightened.

Avila, then 27, a former Navy man with no criminal record, was babysitting Dylan and the boy's 19-month-old brother, Nicholas Macias, at the request of the boys' mother, Marcelina Macias. Avila and Marcy, as she was known, had become friends less than a year before, while both were employed at Roto Rooter, and Avila, and sometimes his mother, helped Macias, then 25, care for her four children; Macias was studying for her GED and whenever he was free, Avila helped out. That's what he'd agreed to do the night of March 29, 2000. After Macias left the house sometime after 6pm, and the two young boys moved off to a shared bedroom to play (their older siblings were at a relative's house), Avila settled in to watch the game.

It was less than an hour later when Avila looked up and saw Dylan in the hall. Dylan called Avila's name; Nicholas wasn't breathing, the child reported. Avila, father to a 5-year-old son of his own, could see Dylan was scared. He went quickly to the back bedroom. Nicholas was lying on his back on the floor, his eyes halfway open, Avila would later tell police. Avila picked up the toddler, carried him to the living room and called 911. He was given instructions on how to perform CPR and he did the best he could, he later testified in court, but it didn't work. Avila paged Macias and told her to come home right away. When she arrived, the paramedics were there, working on the lifeless body of her youngest child.

Hours later, just before 1am, doctors at Providence Memorial Hospital told Macias that her son was dead, from massive internal injuries – including a severed pancreas and a colon torn from its blood supply.

A year and a month later, Avila was on trial – facing the death penalty for what the state deemed the cold-blooded killing of Nicholas by Avila's stomping on the toddler's belly. Nicholas "knows the person who's ... supposed to be taking care of him and making sure he's safe is hurting him," El Paso Assistant District Attorney Gerald Cichon told jurors during closing arguments: "He's on his back ... he's looking up. He sees [Avila] with a nice, big size 11 shoe ... over his stomach and it comes down, straight down on [Nicholas'] stomach; that's exactly what happened," Cichon continued. "He saw it all. ... He watched himself get murdered. He is lying there, holding his little tiny tummy after it's been shredded, torn apart ... and he's bleeding from the inside. He just holds it and lays there, afraid, alone, not even his mother to call." That description of the last minutes of Nicholas' life was dramatic and apparently effective: Avila was convicted of killing Nicholas and then sentenced to die.

But whether Cichon's story was an accurate portrayal of what actually happened that evening is another matter altogether.

Now, more than 12 years later, and with the aid of a newly passed, groundbreaking state law that allows for the reconsideration of convictions in which science – or so-called science – played a key role, Avila hopes that modern analysis done by physicists and doctors specifically trained in the mechanics of injury to children will help him finally to prove his innocence.

Jumping to Conclusions

Avila, Dylan, and even Macias told officials that Dylan and Nicholas often played roughly, and that Dylan liked to mimic the wrestlers he saw on TV. That's what the boys had been doing when something happened to Nicholas, Dylan told officials that night in a videotaped interview. That's also what Dylan told Avila while the pair were riding together to the hospital, following the ambulance where Macias rode with her baby, Avila told police. And that's what Macias told Child Protective Services, which conducted its own inquiry into Nicholas' death.

But that account of events was quickly dismissed after doctors, including the county's longtime medical examiner, Juan Contin, said Nicholas' extensive internal injuries were not "consistent" with damage that could be done by his roughly 40-pound brother. At trial, George Raschbaum, the pediatric surgeon who worked on Nicholas that night at the hospital, testified that the baby's injuries were like what he'd seen previously on a patient who "jumped out of a vehicle going 60 miles an hour."

Avila has maintained that he is innocent, did nothing to harm Nicholas, and doesn't know what happened to the baby that night. But that single medical determination – that Dylan's initial account of what happened couldn't be true – set in motion the series of events that led to Avila's conviction. It caused police and prosecutors to consider that Avila, as the only adult in the apartment, had intentionally harmed Nicholas, and it led to Avila's attorneys' incoherent defense of their client. They eschewed the notion that this was a tragic accident caused by innocent play, instead suggesting that Nicholas' death was the result of Avila's clumsiness, or that Macias, before she left for the evening, had intentionally injured the boy.

The problem, however, is that the initial conclusion reached by the doctors who treated Nicholas was not a scientific one, and did not take into account the principles of physics, and specifically biomechanics – put simply, the study of the effect of force on tissue.

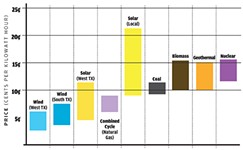

Biomechanics has long been relied on for injury prevention and repair – the development of air bags in vehicles, of helmets to protect football players' heads, of replacement hips and knees – but only recently has biomechanics been incorporated into a criminal law context, to describe with scientific certainty the force needed to cause specific injury. Biomechanical engineering is pivotal to the reconsideration of cases of so-called "shaken baby syndrome," or SBS, and has demonstrated that simple shaking by an adult cannot create the force necessary to kill a child.

"Many if not most non-physicians assume that physicians, skilled in the art of medicine, must have particular knowledge of injury mechanisms. This assumption is wrong," John Plunkett, a veteran pathologist and expert in the diagnosis of child injuries who has been a vocal critic of SBS, wrote in an affidavit filed along with a new appeal in Avila's case. For the most part, physicians, such as Raschbaum, "need not know or apply injury mechanics if they are responsible for diagnosis and treatment," Plunkett continued. "However, if a physician ventures from diagnosis and treatment to speculation of the ultimate force, stress, or energy required to cause injury, he/she must understand mechanics ... and perform or refer to the appropriate experiments."

At the time of Avila's trial, and first appeals, biomechanics was not being applied to criminal cases involving child abdominal injuries, a leading cause of death in children, Plunkett and other experts say. Now, Plunkett wrote, such an analysis prior to deciding whether an injury is criminal or not would be "mandatory."

The argument that Avila's conviction was based on faulty, pseudo-scientific conclusions is at the heart of a new appeal filed in September. The appeal cites passage this spring by state lawmakers of Texas' first-in-the-nation law to allow for appeals based upon relevant and newly ascertainable, or evolved, science that contradicts evidence used at trial. The new statute took effect Sept. 1, and is an acknowledgment that criminal law – rigid and, importantly, wedded to finality – must evolve to keep pace with scientific advances.

Eye of the Beholder

According to court records, the medical opinion that Dylan could not have caused Nicholas' injuries was not the only non-scientific conclusion that influenced the case.

Around 11pm that night, as Raschbaum worked on Nicholas at the hospital, Avila was taken to the El Paso PD to give a statement to Det. Tony Tabullo, then a 24-year veteran of the force. Avila was already a suspect in the case, and around 11:30pm Tabullo advised him of his rights before beginning the interview. At roughly 2:10am, Avila signed a statement wherein he detailed that he had been watching TV when Dylan told him that Nicholas wasn't breathing; per Tabullo's instructions, Avila read and placed his initials before and after each paragraph of the statement, and next to the time and date – 23 separate places in all – before signing off on the document.

What happened next is disputed. According to Tabullo, after he took Avila's statement he found out that Polaroid photos of Nicholas' body had been brought to the police station. Those photos, he testified, revealed a large area of bruising across Nicholas' chest (the bruised area was seven inches by three inches, according to the autopsy report) that resembled a shoe print. Armed with this information, Tabullo said, he returned to Avila and confronted him with what he considered evidence that Avila had stomped on the baby's chest. Tabullo asked Avila if he could see his shoe; Avila complied. "Well, I asked him," after inspecting Avila's sneaker, "do you want to tell me the truth?" Tabullo testified. "He said yes. He shed a few tears and started telling me the truth."

The truth, according to a second statement Tabullo said Avila offered, hours later, at 5:46am, was that while Avila was watching the basketball game at Macias' apartment he got up and went to the bedroom where Nicholas was alone. "I saw him laying on the floor," reads the second statement. "I don't know what came over me, but I walked over to him and stamped on him with my right foot." Avila then allegedly picked Nicholas up and brought him into the living room where Dylan shook Nicholas to try to "wake him up" and then hit him on the chest with a magazine. Avila called 911. Why had he done it? According to the second statement, it was because he was "jealous" that Macias paid so much attention to the toddler.

According to Avila, Tabullo fabricated that second statement. He said that when Tabullo returned to the interview room where he'd been left after making his first statement, Tabullo confronted him with the photos of the alleged shoe-print bruise. Avila said he knew nothing about the injury, he testified in court. Tabullo told Avila he would have to wait a while longer in an interview room. Tired, Avila asked if he could leave; no, not until Tabullo was "done with you," he testified. Avila was tired and was falling asleep as they talked, he recalled. "I said, 'Is it okay if I go to sleep,' and he says, 'Yes,'" Avila testified. "He goes, 'I just need to make some changes on the statement.' He says, 'If you want ... I'll wake you up when I'm done.'" And that, said Avila, is what he did. When Tabullo woke him up later, Avila said, he was told only that he needed to sign his statement again, and that he could then leave. Avila says he did as he was told – without ever reading the new statement. He was then arrested.

Although there is certainly reason to suspect the validity of the second statement – it was conducted by Tabullo alone and was not recorded, and unlike the first statement, Avila did not initial any of the paragraphs, though Tabullo said that's because Avila told him that he trusted the detective and didn't need to go through that – the damage was done. Not only did police now have an inculpating statement, but also "proof" that the bruised area across Nicholas' chest was caused by a shoe.

Where that idea came from isn't clear, though it may have originated with a paramedic who tended to Nicholas at Macias' apartment, says Cathryn Crawford, Avila's lead attorney. Nonetheless, by the time Avila got to trial, the idea that the bruise was shoe-shaped was set in stone. In photos, the bruise appears large and relatively ovate, but without any detail to suggest it was made by a shoe and not by some other generalized force. According to the report of a Department of Public Safety forensic examiner asked by prosecutors to compare Avila's sneaker to the bruise, there was, unequivocally, no match. But for the principals involved in the Avila case, looking at the bruise was akin to looking at the clouds, says Crawford. "You see what you want to see."

And everyone, it seems, wanted to see a shoe: At trial, the state's experts – surgeon Raschbaum and ME Contin (who conducted Nicholas' autopsy with Tabullo present) – noted that the bruising resembled a shoe print, as did the defense's ME expert, Fausto Rodriguez, who conceded the point during cross examination. Added to the doctors' opinions that the force needed to generate such an injury could not have been caused by a child, but – and also without any quantitative underpinning – most certainly could have been caused by Avila, the die was cast.

"Is a 4-year-old capable of causing these kinds of injuries?" prosecutor Cichon asked Raschbaum. "It would be unlikely. I guess ... if you go from a height of 20 feet and you drop somebody, I guess it's a possibility," Raschbaum replied.

"So normal playing in a household ...," Cichon began.

"No, no, no, not this," Raschbaum interrupted.

"... would not be possible?" Cichon finished.

"No."

Shaken Presumptions

That assertion is inaccurate and without scientific merit, according to forensic pathologists, a physicist, and a biomechanical engineer asked to review Avila's case. The results of an experiment conducted by renowned biomechanical engineer Chris Van Ee demonstrate that by jumping onto Nicholas from just 18 inches above the floor – the height of a small, blue-framed child's bed in the room where Nicholas was found unresponsive – Dylan could have created up to 500 pounds of force to his baby brother's abdomen, enough to cause the massive internal injuries the child suffered. "These impact forces are in excess of those that are known to result in serious abdominal trauma," Van Ee concluded in a report filed with Avila's appeal. That finding echoes an earlier one by physicist Richard Reimann, who also conducted a study – like Van Ee, building a torso out of materials sufficient to simulate a child of Nicholas' size, and measuring the force delivered during the experiment (in Van Ee's case, by a young child roughly Dylan's size jumping repeatedly onto the target) – to determine whether Dylan could deliver enough force to sever Nicholas' pancreas.

Reimann also found the force great enough to cause damage, and that compression from the abdomen against the child's spine could cause the avulsions. "If a child were sandwiched between the floor and a falling object, the spine could act as an anvil to concentrate the stress and sever the pancreas," he wrote in an affidavit. "A pouncing playmate [mimicking TV wrestling] who lands full force ... on the abdomen of a child lying on his back on the floor could inflict grievous injury. Such results were predicted by the theory and physically demonstrated here." In short, says attorney Crawford, "I think that this is a case where scientific evidence really calls into question the reliability of the conviction," demonstrating that Nicholas' death was a "tragic accident" – exactly the kind of case that newly enacted Senate Bill 344 was intended to address.

SB 344, authored by Houston Democratic Sen. John Whitmire, passed this spring on its third try in as many sessions, and without opposition from either the prosecutors' lobby or other lawmakers. The new statute expands the law to allow inmates convicted using outdated or "junk" science the ability to appeal those convictions – including specifically in cases of "infant trauma," according to the statement of intent Whitmire included with the bill. "So this case is ... the poster child case for SB 344 and the reasons that led to passage," argues Crawford, who notes that Avila's is the first appeal of a capital case filed under the new law.

El Paso District Attorney Jaime Esparza does not agree that Avila's case falls under the new law. In a motion filed in October on Esparza's behalf, prosecutor Tom Darnold argues that there is nothing new about the science involved in the case that would warrant review. "Avila acknowledges that the relevant scientific knowledge, that is, the physics of impacts, dates back to Newton and has not undergone significant change since Avila filed his first writ application" 10 years ago, reads a motion to dismiss the case. And even "Reimann notes [in his affidavit] that his analysis of these types of issues is 'based on introductory physics normally presented in a general physics course required for biological, health-science, and pre-med students,'" Darnold noted. As such, the "materials Avila has submitted ... defeat his claim that the scientific knowledge, or the method on which that relevant scientific knowledge is based, has changed since the time he filed his first writ application." And the fact that biomechanics was understood and practiced at the time Avila was tried means only that his lawyers didn't exercise "reasonable diligence" in seeking out that knowledge to present at trial. The plain language of the new law, he notes, "does not authorize the consideration of the merits of a subsequent writ ... based on scientific knowledge that was previously available but not commonly used, or based on scientific knowledge that was previously available but simply was not sought out by the doctors or attorneys in the case."

While it's true that biomechanics takes basic Newtonian physics – the law of bodies in motion – and applies it to living tissues, there is nothing at all static about the science involved, says Peter Stephens, a retired forensic pathologist. And when he hears people dismiss the science as not new or say something like, "'We've moved beyond Newtonian physics now,' most of us just roll our eyes." The fact of the matter, says Stephens, is that using biomechanics as a diagnostic tool for childhood injury is fairly cutting-edge – particularly when it comes to assessing abdominal injuries, like that which ultimately killed Nicholas.

The science was first used in this context to show that "shaken baby syndrome" – the death of children with a trifecta of symptoms, including subdural hematoma, but sometimes without any outward sign of obvious head trauma – could not be caused by shaking.

The creation of SBS as a diagnosis is some 40 years old, and was proposed by just two doctors who, after seeing children die from a certain set of symptoms but without outward trauma, posited, well, "people shake their kids for discipline," said Stephens, so maybe that's what caused the kids' deaths. That was all it took: "It was off to the races," said Stephens. Veteran and well-respected pediatric forensic pathologist Janice Ophoven says that SBS "basically became codified as fact by word-of-mouth, not by the scientific method." The diagnosis persisted for decades, even after a groundbreaking biomechanics study debunked SBS theory in the late Eighties. In that study, researchers found through physical testing that human adults could not generate the force needed to kill an infant by shaking alone.

Ophoven has dedicated more than 30 years to studying the causes of pediatric injury and understanding the forces needed to cause fatal abdominal injuries. Abdominal injuries are common in children, whose internal organs are arranged differently than those of adults, and whose protective musculature is far less developed. While fatal abdominal injuries are commonly associated with seat belts or other restraints, they are also often caused by "focal" injuries to the abdomen, such as by bicycle handlebars – injuries that are often deadly.

With unwitnessed accidents, the assumption is that foul play was involved. Ophoven understands well that impulse. Early in her career, she said, she and others worked hard to convince police and prosecutors that child abuse was real and that the perpetrators, often parents, should face justice. Now, she says, the pendulum has swung in the other direction – indeed, even Ophoven said she once believed that SBS was real. It took time and scientific evolution, she said, for her to understand "very clearly ... the paucity of science sitting underneath many of the conclusions we had drawn."

In particular, it took the application of biomechanics to change the course of things – and that is now being applied to understanding abdominal injuries in a way that should, in theory, help to prevent the decades-long legacy of questionable convictions that occurred with SBS. "The forensic pathologist, from day one of their specialized training, is confronted with the effects of force on tissue," said Ophoven. "The field is, in essence, an applied science of biomechanics. ... So whenever we look at a car accident, or look at a child that has had a handlebar accident ... whenever we are evaluating an injury's potential ... we are in essence applying principles of biomechanics." But doctors aren't engineers, and cannot make those decisions in a vacuum. Essential to a modern pathologist's job, she said, is taking advantage of the best science available by bringing in biomechanical engineers to determine, exactly, whether an injury could be accidental. "If [a doctor] could be charged with malpractice for failure to do an adequate job as a forensic pathologist, trust me, overnight these consultations [with engineers] would be taking place," she said. "So the simple question in Avila['s case] is: Was biomechanics being applied, scientifically and appropriately, in the analysis of blunt force trauma to the abdomen at the time of Mr. Avila's trial? And the answer is no."

Staying the Course

According to the state, however, the doctor who treated Nicholas and the ME who performed his autopsy did apply principles of biomechanics (although neither doctor actually mentioned the science or its application by name), and still concluded that the injury was more likely deliberate than accidental. "Doctor, can you quantify the force necessary for this blow to have transected [Nicholas'] organs?" prosecutor Rick Locke asked ME Juan Contin.

"I'd say considerable force," Contin replied.

"And define considerable force," Locke said. "Well ... you see, to be able to press on the abdomen to cause the crushing against his spine considerable force," Contin explained, later concluding that it was not an accident that caused this damage: "This you see mainly in traffic accidents, children who are not buckled," he told Locke.

"[C]ould this type of injury be accidental, someone accidentally harmed a child to this degree?" Locke asked.

"I don't think so."

In the motion to dismiss Avila's appeal, DA Esparza argues that neither Contin nor Raschbaum testified that Dylan could not have created the force needed to harm Nicholas – in other words, they did not provide false quantitative information; rather, they simply disagreed in their qualitative assessment of how that force was applied. "The 'quantitative' scientific facts pleaded by Avila may show that Dylan could have generated up to 500 pounds of force by jumping on Nicholas, but that 'quantitative' fact in no way proves the ancillary 'qualitative' scientific issue of whether such force could possibly cause the massive internal injuries inflicted upon Nicholas," reads the motion filed Oct. 3. In the prosecutor's argument, the question of whether Avila is responsible for murder is not one of science that can be cured by having it reviewed under the state's new law, but rather one of expert opinion. "This issue is not black-or-white, like, for example, a DNA issue where the science may conclusively show that the blood at the scene either came from the defendant or did not come from the defendant," reads the motion. And in the absence of either Raschbaum or Contin recanting their prior opinions, there is no way to prove, "conclusively" that either doctor's opinion was wrong.

Had the science of biomechanics actually been common in forensic analysis at the time Raschbaum and Contin saw Nicholas, and had either doctor performed any actual quantitative analyisis of the force it took to injure the child, it would seem logical that either, or both, would have testified as such. But neither did.

Still, the state's insistence that only a matter of opinion is at stake in this case highlights an ongoing tension at the junction where science and law intersect. The criminal justice system, says Deborah Tuerkheimer, a professor at DePaul University College of Law, is "a massive institution that is, in all sorts of ways, primed to stay the course," even as science evolves and calls into question the basis for convictions past. In that way, DNA has played an important role – not only in righting wrongful convictions, but also in creating a false sense of certainty. "DNA as a paradigm for innocence is really problematic as applied to many cases," says Tuerkheimer, whose groundbreaking research on SBS and the law will be published in a book next year. "We're going to come to a point where we don't have more DNA to test to find innocent people," yet we know the problem of wrongful convictions "goes beyond" those cases where DNA is available to test, and to provide "this level of sureness [of innocence] that we've become accustomed to," she said. "We need new ways of thinking about innocence; we need some new procedures, some new laws, to sort of grow more comfortable with the idea that we're not going to have that level of certainty in a number of cases, but that we should nonetheless be concerned."

The problem with cases where there is no DNA – those involving SBS, for example – is the issue of "differential diagnosis," says Tuerkheimer. That is, as in the Avila case, that no one test, no one person, can say definitively whether Dylan did or did not inadvertently injure his brother. "I do think it is sort of human nature to want some sort of satisfying narrative," she said. Still, this does not mean that the advances in science – such as the application of biomechanics in cases such as Avila's – don't have the power to highlight – and to right – potential miscarriages of justice. That's why laws such as Texas' new statute are so important – and encouraging. "I think it is an illustration of the move toward expanding the categories of cases that we're willing to take a good hard look at," said Tuerkheimer. "As a trend in the direction of pushing against finality as a norm that doesn't get disturbed or disrupted except in the most extraordinary of circumstances, I think it is a good thing."

How the new law will be applied in practice by the courts remains largely unknown. Avila's is only the second case – and the first death penalty case – to be filed for review under its provisions. Avila's attorney Crawford maintains that it is exactly cases like Avila's that the statute was meant to review. Put simply, had biomechanics been available to his defense team and presented to a jury, it is hard to imagine that Avila would ever have been convicted – let alone sentenced to die.

Ultimately, what Crawford wants is for the new law to be applied as intended, and for Avila to be granted a hearing in which a district judge can evaluate the impact of the science on the conviction. And she does not buy the state's assertion that this case rests on a question of "qualitative versus quantitative" evidence. "I think the answer to that question is contained in the state's closing argument," she said. Indeed, in closing, prosecutor Cichon reminded jurors that "all" the doctors testified that Dylan was "incapable" of causing Nicholas' injuries, "unless he's jumping off a 20-foot height onto the stomach of the child. So we know Dylan can't do it," Cichon argued. "Take a look at [Avila]. He's a big guy. He can generate that force," the prosecutor continued. "He can do it. He's the only one."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.