In the Name of Ann Richards

AISD's School for Young Women Leaders is a district showcase – does its glittering reputation hide a darker side for teachers and students?

By Richard Whittaker, Fri., Aug. 30, 2013

Ann Richards was no saint. Talk to any veteran reporter and they'll pull out a story about the hard-drinking, hard-talking, silver-haired pit fighter of Texas politics. But she believed in redemption. She once said, "I believe in recovery, and I believe that as a role model I have the responsibility to let young people know that you can make a mistake and come back from it." When the Austin Independent School District opened the Ann Richards School for Young Women Leaders in 2007, it was that pledge turned into brick and mortar: to give a college opportunity to girls who weren't necessarily top of the class, but had potential, and to help them give back to the community.

That's the mission Kate Mason-Murphy signed on to when she joined the school as a physical education teacher in August 2008. Mason-Murphy – or Coach Mason, as her students call her – wasn't looking for a regular teaching job. In 2006, she moved to Austin and was organizing special events for Toyota. She picked up a part-time job teaching PE at ACES (Alternative Center for Elementary Students), the district's campus for troubled elementary kids. But when she heard about Ann Richards, she knew where she wanted to go. She said, "I had started a girls' club, I had worked with Title 1 [at-risk] kids, and I love working with that age group. It was a perfect fit." She went to find the campus' founding Principal Jeanne Goka. "I said, 'I'm the one that's been hounding you, I think I'd be great for this job.' "

Five years later, she still believes in the mission. But her faith in the campus' administration is shattered. Less than two years after successfully battling cancer, and weeks before the end of the school year, she was fired and banned from campus. Not, she argues, for any major sin or rank incompetence, but because she stood up for herself. "Teachers are upset and scared," she said. "People get bullied and mistreated every year."

The Ann Richards School is undoubtedly the district's golden child. The district's only single-sex campus, it provides a STEM-centric curriculum (science, technology, engineering, math) for girls in grades 6-12. Its test scores are (in Texas Education Agency terminology) "exemplary." Students have provided thousands of hours of community service and mentoring. It has its own charitable foundation, putting extra money and resources into the campus. Plus, with the name "Ann Richards" painted on the sign, it belongs to a political legacy.

Yet the district is peculiarly, almost uniquely defensive about the school. In reporting this story, the Chronicle asked to speak to campus Principal Jeanne Goka and Chief Schools Officer Paul Cruz. We were initially told that they were busy, due to the imminent start of the school year, but that district staff was attempting to schedule some time with them. After a week, we offered to submit a list of questions for each: The district agreed. What we got back was not individual answers from Goka or Cruz: Instead, they were answers relayed and rewritten by Alex Sánchez, executive director of the AISD Communications and Community Engagement department.

It seems odd that campus and district staff would not want to talk about Ann Richards. After all, this year it graduated its first class. Their scores were high, and every single student was headed to a four-year college. The school and the foundation touted the fact that its students had earned $2.6 million in merit-based scholarships. In short, the campus had done its job of preparing young women for college. Sánchez said, "Having just graduated their first senior class, the principal and teachers are proud to have seen their vision become a reality."

The Growth Plan

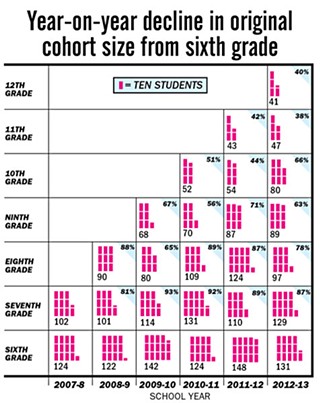

That was true, at least, for the students who made it to graduation. There were 52 students in that class – compared to 102 in the original cohort that entered at seventh grade in the 2007-2008 school year. Add the 11 students who joined that cohort in later years, and a total of 61 students moved or transferred out; only 41 of the original 102 remained.

And it was not just one year, or one cohort. The pattern of attrition in the graduating class of 2013 is repeated in every grade, and has done so since the campus opened. Last October, the AISD board of trustees requested a breakdown of admissions and exit numbers at Ann Richards, and the figures were startling. In the 2012-2013 school year, only 38% of the 124 sixth-graders who entered in 2007 remained by 11th grade. Similarly, in that school year 13% of the rising sixth-grade class left before seventh grade. Every year since Ann Richards has opened, each rising grade has shrunk. If any other AISD school suffered that kind of constant attrition, a red flag would have been raised.

But when Mason-Murphy signed up, she went in with a "clear eyes, full hearts, can't lose" attitude to a campus of pure potential. The school offered her a position: 50% PE and 50% technology specialist. Then, on her very first day, they changed the description, to 50% PE, 50% English as a Second Language. Eager to be there, she obtained the ESL certification, and then broke some good news to the administration: During the interviews, she learned she was pregnant. Their response was not what she expected. She said, "They were a little irritated."

The following year, things still looked good: She loved her work, she loved the students, she was headed out of her probationary year. Then she found out that she was pregnant again, and it was the same surprising reaction. Her cardinal mistake was simple: She wasn't putting the school ahead of her own life. She said, "The two assistant principals that I was close to told me absolutely do not tell Jeanne Goka, do not tell [Assistant Principal] Kris Waugh, [and] to join the union before I did anything." What Goka and the administration expects from teachers was simple, she said: "No children, and be willing to work 80 hours a week for piddly pay." Moreover, they warned her that if Goka knew she was pregnant, she would stay on a one-year contract and lose the security of a three-year position.

The contract issue became moot in 2011, when the district declared financial exigency and got rid of three-year contracts. However, as part of the cost-cutting, Mason-Murphy's hours were cut from full-time to 67%. Initially, she saw this as a positive: After all, she had two infants to look after, so having more time available could only help. The following year, her hours went back up to 83%. However, she remained classified as part-time, even though other staff with less experience were working the same hours but pulling down full-time salaries. She said, "I got the same number of kids stuffed into fewer classes, but I took a $7,000 pay cut."

It was during this period that Mason-Murphy says she endured what she describes as administrative harassment, reaching its height in February 2012 when, with little notice, Goka took personal charge of her annual evaluation. "She knocked me off for stupid things," Mason-Murphy said, such as using a water bottle rather than a cone to mark out the running track. "I had seven girls wearing a Texas State University T-shirt from their college field trip, but they weren't wearing an Ann Richards shirt, so she gave me 'below expectations' on classroom management. I feel sure that's not what the [TEA] had in mind." She appealed Goka's evaluation to the district, claiming that Goka's report was unfair, inaccurate, and even covered times when Goka was not even in the room. On a second evaluation by district staff, she was classified as proficient in all areas. "Jeanne insisted on averaging [her evaluation] with that one," Mason-Murphy said, "and because of that average, I was put on a growth plan." In AISD terms, a professional growth plan is effectively a probationary status, requiring specific improvements to avoid potential termination.

Excellence by Attrition

Then, on March 27, 2012, Mason-Murphy was diagnosed with breast cancer. She claims that Goka, rather than showing sensitivity to her situation, made it impossible for her to fulfill her growth plan. The principal twice declined to let her attend a required Socratic questioning seminar. The same happened when she tried to schedule a session on lesson planning. "Instead," Mason-Murphy said, "she made me chaperone a seventh-grade college field trip." Finally, in October 2012, Mason-Murphy took the radical step of filing a professional grievance against Goka.

Even though the deadline for her current growth plan was not set to expire until Feb. 22 of this year, in January Goka dropped a bombshell: "Jeanne told me, 'regardless of what you do, you're on a growth plan next year.'" Soon, Mason-Murphy was given an option: Quit, and be given the opportunity to apply elsewhere in the district, or be fired and never work in AISD again. She said, "I told her, 'you know what, Jeanne? I'm willing to take my chances.'" Previously, she'd been expecting to get a simple letter of nonrenewal, meaning the campus would not be giving her another one-year contract. Instead, on Jan. 31, she received a contractual difficulty notice – the first step to being fired. Mason-Murphy fired back with a second grievance complaint against Goka, alleging "a multiyear pattern of harassment and discrimination." Goka pushed further, and on May 20, Mason-Murphy received her official letter of termination, signed by AISD Board President Vince Torres. She said, "I keep getting certified letters saying 'you're fired, you're fired, you're fired.' How many do I need?"

Mason-Murphy is not alone, but she is alone in feeling she can speak publicly about her experiences. Other members of the Ann Richards community echoed what she said, but were afraid to speak publicly. Parents worry about what will happen to their kids. Teachers worry about what will happen to their careers. Former teachers just want to put the whole experience behind them. Moreover, they feel that the grievance system is so heavily biased that complaining is pointless. Mason-Murphy has experienced that firsthand: The first two levels of her grievance were heard by Goka – the very person she was complaining about.

AISD declined to comment on either the facts or the central complaints in Mason-Murphy's grievances, as they are still pending a hearing by the board of trustees. However, other former staff report a similar experience: that there was an inner and outer circle at Ann Richards, and that if the administration didn't like them, they would find themselves classified arbitrarily as part-time or put on a growth plan. The district denies any misuse of the plans. Saying that they deal with "personnel matters and [are] private," Sánchez said that their goal "is to seek better outcomes."

Yet teachers may not be seeing those outcomes. Some quit; some even left education altogether. One former staff member recounted, the year after leaving Ann Richards, taking a position at one of the lowest-scoring, most challenged campuses in the state – and finding that a better, more rewarding experience than the district's premier school.

The system Mason-Murphy and her colleagues describe is one of cripplingly high expectations. Teachers are expected to work every hour possible, while students are simultaneously placed under extraordinary pressures.

For Teri O'Glee, executive director of the Ann Richards School Foundation, that's only to be expected in a new, experimental school. She said, "In the early years, there are challenges as there are in any start-up." It's no surprise that O'Glee makes that "start-up" comparison: A business consultant by trade, she joined the foundation in December 2012 after periods of working with charter operator KIPP in both Dallas-Fort Worth and Austin. She said, "Whenever you have a start-up, and I've been involved in several, for the first couple of years there is a tremendous amount of work that has to be done."

Mason-Murphy found that response frustrating, because what she saw was not teachers quitting because the work was too hard: It was teachers being forced out because they don't fit the program. She said, "We have the highest turnover in the district at a premier school with zero discipline problems."

Ann Richards actually has on occasion had a lower staff exit rate than the district average: 7.7% in between the 2010-11 and 2011-2012 school years, compared to an AISD average of 12.2%. But there was a startling drop in staff after that year. Across the summer of 2012, AISD lost 21.9% of its teaching staff to retirement, resignation, or termination. Ann Richards exceeded that average, losing 23.7% of its staff. By comparison, other high performing campuses had much lower losses, like Gorzycki Middle School (17.7%) or McCallum High (16.5%).

There's a startling symmetry in Mason-Murphy's allegations: The culture of excellence through attrition doesn't just hit the staff. If kids don't hit the targets defined by the campus administration, they're gone. And that's the exact opposite of what Ann Richards is supposed to do.

Cherry-Picking and 'Exiting'

Unlike a neighborhood school that accepts every student in its attendance zone, or a pure magnet school where grades are paramount, Ann Richards dances to its own rhythm and picks its own dance partners. Students go through a pre-screening process, and while grades count, other factors are taken into account as well. To begin with, in each round of admissions, 75% of positions are reserved for kids from Title I campuses (generally, those with over 40% low-income populations). Then each prospective student has to submit a portfolio of work, scorecards, attendance reports, and letters of recommendation. If and only if her application is deemed acceptable by the administration, her name is entered into a lottery. Mason-Murphy said it was clear to the staff that there was "cherry-picking" of students at the front end, selecting the best and dumping the rest, or for arbitrary reasons blocking siblings of existing students or district staff. She said, "We all believe that the lottery is rigged. There are specific people that they do not want in, and they do not get in."

But the cherry-picking doesn't stop at the lottery, and for Mason-Murphy it explains why the graduating class was so small. It was what she and other teachers call "exiting." At the end of each semester, each grade-level team would present their recommendations for each student to the administration. In part, this was to assess each student, to see what extra intervention or support she needed. Mason-Murphy and other teachers saw another purpose: to work out which students were providing the scores the administration needed to maintain their perfect image. She said, "We go through every single girl, discussing every single girl. Stay, go, stay, go. It's always tearful. The teachers fight for the girls that need to stay. It's awful. It's a brutal way to do this."

According to district communications chief Sánchez, "According to the principal, the goal is not to 'exit' students but rather help them become successful students at the school." He added, "There are times, however, where the parent, teachers, and student agree that ARS may not be the best place for them." Mason-Murphy sees it differently: that it was made clear to parents that their daughter was not wanted.

But why purge when you're already accepting only the best kids? Because Texas education is a numbers game, pure and simple. The higher your numbers, the better your chance of survival. In Michael Brick's book Saving the School, Reagan High School principal Anabel Garza laid out the fight for survival at a campus classified as academically unacceptable (see "Where There's a Heartbeat, There's Hope," Aug. 17, 2012). It's a hideous reality, but if a handful of low-performing students can take your campus down and ruin the school for everyone, sometimes you make tough choices. For Mason-Murphy and other staff, this was the same phenomenon, but for a high-performing campus. If a student wasn't getting excellent grades, if she wasn't heading to a four-year college, then she would be pushed out.

Sánchez said that Goka had "referred to the first two classes that started as sixth- and seventh-graders at ARS as 'a brave bunch.' Those students who stayed at ARS were risk-takers who found their voice in the creation of a new school, believed in the mission statement, and developed loyalty and commitment to the new school."

What about the attrition rate? He said, "As for the students who left, the school was simply not the right fit for them." In part, he said, it is because the school is still fledgling, and does not have many of the resources available at other campuses. He passed on an anecdote Goka had told him, that one student had told her, "Ms. Goka, I know your band is going to be great, but I don't want to wait that long. I want to go to a bigger school that already has a bigger band."

The students knew what was happening. Students like Jessica Rico, who was part of the first graduating class and feels that her time on campus has left a bitter taste in her mouth. "You go to our graduation ceremony, and there're these amazing 52 girls. But we're only amazing because they kicked out everyone who was 'bad.' They weeded." She saw how her homeroom halved over time. She said, "I felt like, if they didn't think you were going to go to college, you didn't graduate with us." Moreover, just as the teachers felt their personal lives counted against them, she saw students who made mistakes get pushed toward the door. Tellingly, she said, "At every school, there's someone that's pregnant – but not at Ann Richards."

If the teachers are worried about their jobs, the students are hammered by fear of failure. Rico went from Bedichek, where homework was a rarity, to Ann Richards, where it was every night in every class. "After a while, you get used to being sleep-deprived," she said. "Doing all-nighters – that is what Ann Richards is. You can get up in the morning and look wretched and no one cares because it's all girls."

She's heading to UT-San Antonio, where she plans to study nursing, but she's not prepared to let Goka's administration claim it was all because of their campus. She said, "I talked in my senior speech about how Ann Richards gives themselves too much credit." Rather than feeling academically ready, she feared that many of her peers feel burned out on education. Moreover, she felt students were poorly prepared for the realities of a four-year college, and "most of us got zero to crummy financial aid, unless you're in the top 10 percent."

When Rico read her senior speech, Jailyn Bankston was listening. A sharp-minded, clear-speaking young woman, she's headed to Sam Houston State to study criminal justice. She'd like to be a lawyer, and has aspirations for the FBI. But where backers compared Ann Richards to a "start-up," she saw a laboratory. "We were the guinea pigs," she said. She has a profound sense of right and wrong, and was angry when she saw students being exited. "I never got the point of kicking people out," she said. "If your grades slipped, you were put on academic probation, you were given a semester, and you were kicked out."

Technically, it's almost impossible to be kicked out of Ann Richards. What she saw instead was less-than-subtle pressure on some kids to exit. For example, she said, "One of my friends left because a principal told her she would fail the grade unless [she] left." But it wasn't just about grades: She recalled the spring of her sophomore year, when one student discovered she was pregnant. Bankston said, "She didn't see it as a setback. The administration saw it differently." Rather than finding a nurturing environment, she was told she was no longer hitting the required grades and asked to leave. "We were confused," Bankston said, "because her grades were picking up, but it became clear that they had an image to uphold."

Rico and Bankston represent what Ann Richards is supposed to give the community: a strong sense of social justice, and a commitment to health and well-being. That's why Coach Mason's departure sits badly with both of them. Bankston said students knew there was a "golden group" of teachers close to Goka, and Rico backs up that impression: "It was like high school for teachers." Even when Coach Mason was diagnosed with cancer, Rico said, "she wasn't moping around, trying to get people to feel sorry for her." Much to the chagrin of the administration, she said, "In my senior speech, I talked about how she motivated us and was positive and enthusiastic about everything."

Is Anybody Listening?

When she talks about her former students, there's pride in Mason-Murphy's voice, matched only by the anger for the kids who didn't make it to graduation there. She said, "Ann Richards was not well behaved. She was loud, she was rowdy, she was bawdy, she drank, she smoked, she played bridge. But we expect these girls to be perfect little robots, and if they're not, we exit them."

Even without anecdotal evidence and specific allegations about how Ann Richards is run, the high attrition rate of staff and students is starting to raise a red flag in the district, and interest at the foundation. According to O'Glee, there are two points of exit, at eighth and 12th grade. The standard line from the district, repeated by O'Glee and district trustees, is that some girls just get to their high school years and get tired of uniforms and spending all their time with other girls, so they head back to their home campuses. Moreover, O'Glee said, "We're not backfilling [when students exit]. It's very rare that we're adding more students in 10th, 11th, and 12th grade."

AISD Trustee Lori Moya is one of the campus' biggest boosters, and touts its successes. "For some girls, it's like a home away from home," she said. "I'm not over there very often, but when they see me, they hug me." While she has heard concerns about exiting ("Not very loud," she said, "but I have heard that"), she echoed O'Glee's thinking that the student-loss rate "is probably to be expected. It's very new. Families and students were probably very interested, but weren't sure if that's the right fit for their child."

Not everyone agrees. Trustee Ann Teich said, "There are some things you can't ignore, and that's attrition." Teich, a former AISD teacher, is no fan of single-sex education: She voted against the plan to convert Pearce and Garcia into single-sex schools, and only voted for the proposed boys academy as an equity issue (in short, having a girls school and no boys school leaves the district open to lawsuits). The exit rate only increased her concerns, both as a matter of social justice and of budgeting. "It does raise some flags in my head about how effective is the program," she said. "If it's losing kids and losing state money because of that, then it's a cost issue."

But the real issue for the district is: This is old news. It's not just the 2012 report to the board. In 2011, the administration was aware of a report showing serious concerns about the admissions process. Respected Penn State education researcher Ed Fuller found that the TAKS math scores for rising fifth-graders entering Ann Richards were off the charts. In the two years prior, 80.4% of incoming students were classified as above average, and only 9.8% below average. Those figures not only exceeded the district norms, but were actually better than the designated magnet schools that were recruiting based solely on grades. Fuller bluntly called the idea that there is a level playing field at Ann Richards "total BS." He added, "Richards has the highest performing incoming sixth-graders. ... This is essentially a magnet school or private school funded by taxpayers."

The board knew about this report two years ago, but Trustee Robert Schneider said there's been no real discussion of the numbers – in part because the board has been so preoccupied with Eastside Memorial and other more obviously troubled campuses. However, he was perturbed by the lottery system, noting that "more emphasis is placed on filtering students by application grade, versus the original proposed admissions guidelines." While he said there's a "growing concern" about the system, "we as a board have not taken a real deep dive into admissions policy and administration." If they do, he said, "there would probably be some tweaking."

However, the administration sees no reason to examine, change, or tweak the system. When asked if he thought the lottery system worked, Sánchez simply said, "Yes."

The situation evokes another Ann Richards quote. As she told the Democratic National Convention in 1988, "We're not going to have the America that we want until we elect leaders who are going to tell the truth – not most days, but every day." That also means they must want to listen to truth-tellers and act on what they hear. Schneider has conceded that the board has done nothing, even though it is aware of issues with the admissions process.

Moya was skeptical that the anonymous complaints remained anonymous because of fear of retribution. She said, "It's unfortunate that people will say that they're afraid when they haven't even made an effort." After all, as she noted, the board can only respond to complaints. But Mason-Murphy said she believes she was fired before her grievance process could reach the board and she could have a full hearing.

Similarly, when Fuller raised his questions, Superintendent Meria Carstarphen claimed that he didn't understand the numbers. The same happened when University of Texas researcher Rebecca Bigler co-authored a paper on single-gender education, using Ann Richards as a case study: The district's response was to allege she was biased against single-sex schools (see "Uncontrolled Experiments," Dec. 9, 2011). As one education activist put it, the board ignored the East Austin community when they tried to stop the troubled Eastside Memorial being turned into a charter school. Why would they expect better treatment complaining about the district's prize campus?

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.